DEC accepting public comment to determine whether to allow fracking

By Alison Rooney

The Philipstown Garden Club’s Conservation Committee and Putnam Highlands Audubon jointly presented an informational seminar on fracking in the Hudson region last Saturday (Nov. 19) at the North Highlands Fire House.

The aim of the program, as detailed in introductory remarks by Elise LaRocco of the PGC, was to help the audience understand the issues, concerns and results of fracking now, and for future generations. Connie Mayer-Bakall of Audubon added that Audubon has historically based decisions on “sound science,” and that Audubon is concerned about effects on forest fragmentation and water sources which then affects wildlife. The talk, which included a projection presentation followed by questions from the audience, was presented by Wes Gillingham, the founding director of Catskill Mountainkeeper.

Gillingham, an organic farmer, has worked for the National Park Service, for whom he was a park ranger based in the Upper Delaware River. Although billed as informational, it was quite apparent from the onset that Gillingham was firmly in the anti-fracking camp.

The talk was timely, because currently the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) is accepting public comments (via their web site) before determining whether to permit the process of hydro-fracking, which is a method of extracting natural gas from shale rock formations, to occur in New York State. Currently hydro-fracking is exempt from federal environmental regulation, and is therefore regulated on a state by state basis, however the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is in the midst of a two-year safety review of hydro-fracking, with results expected to be made public by the end of 2012.

The gas industry is not covered by the public “right to know” legal provisions due to the Solid Waste Disposal Act of 1980, which prohibits the EPA from regulating drilling fluids, produced water and other waste associated with the exploration, development or production of crude oil or natural gas.

The fracking issue is of particular importance to those living further north in the state, but of great regional significance here because of potential implications in the Marcellus Shale, a rock formation that underlies much of Pennsylvania and portions of New York at a depth of 5,000 to 8,000 feet and is believed to hold trillions of cubic feet of natural gas. According to material supplied to the audience, produced by the Rusticus Garden Club, drilling activity is expected to focus on areas where the Marcellus Shale is deeper than 2,000 feet. The majority of natural gas in the Marcellus Shale is expected to be retrieved via fracking. The entire Catskill/Delaware NYC watershed is located within the Marcellus shale region.

Chemicals Pose Threat

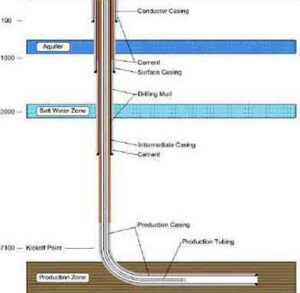

Fracking begins with wells, created in “pads” of three to four acres, drilled down vertically to a depth above the target gas-bearing rock formation. The well is then curved so that the hole is drilled horizontally within the gas-bearing rock. Highly pressurized fluids consisting of water, sand and a mixture of unidentified chemicals are then injected and forced down the well into the ground at extremely high pressure to create or expand cracks and fissures in shale formations thereby releasing the oil and gas contained inside. During the fracking process, the wastewater generated is contaminated with the fracturing chemicals and fluids; this is called flowback.

Other fluids, along with naturally occurring radioactive materials like radium, are brought to the surface. According to Gillingham these fluids can consist of “surfractants, (compounds that lower the surface tension of a liquid, the interfacial tension between two liquids, or that between a liquid and a solid) friction-reducing chemicals, biocides, scale inhibitors and propping agents, all needed to make the gas viscous.” Runoff can result, flowing into nearby streams, lakes, rivers, and, eventually, oceans. Gillingham’s projections stipulated that “each million gallons of hydraulic fracturing fluid contains about 40,000 pounds of chemicals.”

Gillingham began his presentation with tales of how, approximately 35 years ago, “land men” came to his region, offering farmers and other land-owners money for “gas leases,” in some cases as little as $25 per acre — offers which were taken up. In some cases these properties have since been reassessed and given a higher value, based on these very leases, something which the landowners were not aware might happen.

Describing the gas industry as “having a long history of going into places and getting leases before people smarten up,” Gillingham projected a map of Marcellus Shale, noting it was the largest shale deposit in North America and the third largest in the world, and that as you move eastwards, the deposits go deeper and thicker, making it most attractive for the drilling industry. Though fracking has come into the public eye over the past few years, Gillingham said it was not a new concept, and in fact some of the drilling is done using existing pipelines which are now hidden in forest overgrowth. He urged the audience to look at the history of gas drilling, saying “they do test drills, then put downspacing pads in. Then they go back afterwards and put vertical wells in, in between the horizontal ones.

Other Pollution

Gillingham also addressed other modes of pollution resulting from hydro-fracking — air quality being one. He detailed how this occurs, “Air quality is being radically reduced where you have these open pits. Stuff evaporates into the air, toxic air pollution: xylene, benzene, toluene and other possible and probably cancer-causing agents are released into the air from the separation process and tank storage. Natural gases are frequently vented into the air when a well is completed.”

Other potential dangers, according to Gillingham, are leaks and spills, which can occur from the injection process and from the wells, pipelines, flowlines pit, tanks and drums themselves. Another issue is abandoned sites, with Gillingham citing a need to identify and assess the environmental threats of abandoned and orphaned wells, especially as record-keeping was negligible in prior decades with “half of 60,000 wells drilled before 1994 lacking records, records being introduced only in 1966. There is a need for a regulatory requirement that abandoned and orphaned wells and sites in the Marcus Shale be considered and evaluated during the drilling permit review process and during the permit application review process for commercial and centralized facilities. Abandoned wells can migrate into aquifers through fracking.”

Questions Asked

Towards the conclusion of the event, questions were taken from the audience. One was how to counter the law of supply and demand, in which the natural gas supply is seen as infinitely preferable to the reliance on oil and the declining supplies of coal. Gillingham said it was something he heard all the time, “But we need the gas.” He asked the audience to consider “When there’s a toy on the market that’s killing kids we say ‘get that toy off the market.’ Why aren’t we doing that with this?”

Other questions included the linking of recent earthquakes to fracking activity, with Gillingham noting, “seismic activity is well-documented from the pumping down of radioactive waste. There is a creation of areas for fluids to move: hence seismic activity.” Another attendee asked if the technology now existed to extract gas without fracking.

Gillingham replied “We’ve used up most of our natural gas reserves. Now we need to go to more extremes to get it. Drilling down to a pocket, rather than horizontal drilling is a very big difference, scale-wise. Drilling in a pocket is the old-fashioned way.”

State Assemblywoman Sandy Galef, whose district includes Philipstown, said interest in the issue was rising amongst her constituents: “I am getting a lot of emails on fracking. It’s a very important issue for New Yorkers.” She said that she did a poll last January and found responses very divided, with many people also stating that they didn’t understand it. She said she would be testing the question again, and she urged people to express their opinions to their local elected officials. Referring to Governor Cuomo, Galef felt that “he is so interested in getting rid of Indian Point that he is trying to find other energy sources — and he’s also trying to find a balance for jobs upstate.”

In terms of her own point of view, Galef stated “I don’t like this, but I want to see if there are regulations we can put in place to make it safer in some parts of the state. Many of my upstate colleagues are very conflicted — some are supportive of it.” Galef also noted that a suggestion had been made to put a tax on the industry so that they can hire more inspectors. Currently there are only 15 inspectors in New York State, Gillingham thinks at least 300 are needed to oversee things correctly.

The remaining discussion focused on methods of public commentary. There is currently a moratorium on fracking, and permits are not being processed until the law is determined. Gillingham expressed frustration that “this is a political process now, not a scientific one. Until that happens, we want a ban.”

Photos by A.Rooney