Colonial documents provide glimpses of life centuries ago

By Alison Rooney

The Community Room at Beacon’s Howland Library is not known as a particularly nefarious spot. Nevertheless, the lure of what was described as “Dutchess County’s Seedy Underbelly” proved too great for the curious souls who filled most of the seats at an afternoon talk last week.

The talk, which proved to be more lucid than lurid, was given by Dutchess County Historian Will Tatum, who began by noting, “There are those who don’t think the library should be encouraging sex and violence — well there will only be slightly veiled references to these.”

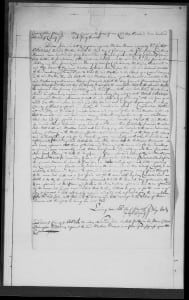

Indeed, those references were inferred by reading and analyzing a trove of what are called “ancient documents,” a newly catalogued set of what are the oldest in Dutchess County’s collection. These documents are largely from the Court of Common Pleas established in 1691 in Poughkeepsie; the first records drawn from there date to 1721.

There have been four county courthouses in Poughkeepsie — some were lost to fires — and all of these documents relate to what was heard in the courthouse itself, reflecting the community at large. First indexed by Vassar Professor Henry McCracken during the 1950s, the collection has since 2012 undergone modern indexing and is now coded by searchable format files.

Currently, the government of Dutchess County is working on a collaborative project with the New York State Archives to create digitalized TIFF images of each document, far superior to the microfilm scans of yore, according to Tatum.

After an explanation of the source material from which his tales were gleaned, Tatum got down to business, regaling the attendees with what he dubbed “the scandals, the not-so-whitewashed lives of our ancestors.” He noted that the paperwork for most (largely civil) court cases consisted of six documents, often in languages other than English (predominantly Dutch) including a declaration, indictment, arrest warrant and verdict, which together show the “arc of the case — interesting bits which give us tiny portals, rather than large drawn-out stories.” Tatum called it “rare to have all of them.”

Debt

Starting with promissory notes, which he called 18th-century credit cards, Tatum explained that “like today, people overspent. The vast majority of cases relate to debt, all different kinds.” For example, in 1734’s John Alsop v. William Coat, Coat was sued for the sum of eight pounds, eight shillings and six pence for “diverse wares, merchandises, liquor and one bullock.”

In another, from 1739 to 1741 Matthew Dubys owed Samuel Monrow “18 pounds for salt, molasses, lead shot, gunpowder, types of cloth, spices, rum, hats and pastorage for two horses.” To show the sums involved, Tatum mentioned that the average farm laborer in that period earned about four pounds annually.

Slaves were considered objects and mentioned in documents accordingly, with one referring to a bill of sale for “Phyllis, a negro wench of 14 years of age”; Tatum reminded the audience that slave auctions were held in Dutchess.

Other debt was incurred for wood planks, a corollary to the lumber mills nearby, which, though they weren’t supposed to be manufacturing (that was theoretically to be done in England), appeared to be doing so as documented in bills for “milled lumber.”

Similar situations appeared with iron processing; a 1751 suit alleged that there was a failure to deliver shipment of refined iron. The military presence in the area was reflected in a 1748 suit brought by 12 individuals suing for back wages for what was essentially mercenary service, claiming a “shorting of soldiers.”

The ‘seedy’ stuff

In a different vein, as promised, the talk veered toward matters sexual, with a 1764 recognizance, a type of bond issued for William Briggs, for “Bastardy.” Tatum noted that “strangely these types of suits are largely from Beekman!” He cited a description of one: “Suzanne Harrington claimed that William Briggs had carnal knowledge of her body several times and a son was born.”

Tatum explained that “Poor Laws” of the time deemed the “municipal government responsible for supporting anyone who could not support themselves. Normally towns would exert themselves to find the father and thus avoid raising taxes.” To do so, “they often relied on midwives to ask laboring women, ‘Who is the father of your child?’ and nine out of 10 times they got a name … Often, justices settled upon someone and told him, ‘You’ve got to pay for the pregnancy and the child’s upkeep,’ which meant sending money every week until the child was old enough to support herself, meaning at least until the age of 10.”

Violence is not just a contemporary police blotter occurrence. Tatum explained that there was one court that met twice a year with three justices per town. He described a typical case: “People just dropped dead. In the 18th century it was not out of the realm of possibility to run across a dead body sprawled across a road or town well. For instance, Robert Kelly, 37 years old, goes to visit a friend’s house, goes out from there, doesn’t come back. His friend’s female slave goes to the well, finds Kelly.

Twelve jurors were called up, looked into the facts of the case to determine if [there was] foul play or not. Then there’s Salvanus Garlic — awesome name — goes to a buddy’s home to fetch a milk cow; goes into his friend’s house, drunk; next day, found dead with a great hole in his head — and the cow nearby. Jury rules: drunk, slipped, hit his head, deemed accident. Death was much closer to people in 18th-century Dutchess County than it is today.”

Want more?

Those interested in learning more should start with a look at the home page for the Dutchess County Department of history at dutchessny.gov/history, or phone Tatum at 845-486-2381.

Images courtesy of Dutchess County Government Department of History