“The delicate relationship between control and accident”

by Alison Rooney

Those unfocused, unproductive, feeling pointless times familiar to all artists; the in-between times, when the next inspiration has yet to overtly germinate: when the fiddling around begins. It was just this kind of tinkering which led artist Susan English from one body of work to another. After a period of doing painted work on canvas, she began making little sculptural pieces, small shapes placed on not much larger pieces of wood. Seeing them, someone remarked “the shapes are so interesting, you should just make them,” and she started doing just that, taking small blocks, drizzling things onto them, then trying that technique directly onto shapes, pouring tinted polymer onto their surfaces.

Pourous Light, English’s new show at Beacon’s Matteawan Gallery demonstrates what evolved from her experiments with that process.

Pourous Light refers to, according to gallery notes, “both the process of creating English’s paintings and also to the idea of putting oneself in the path of light, feeling oneself in the present, and for a moment dissolving ego and self and becoming the thing that one is observing.”

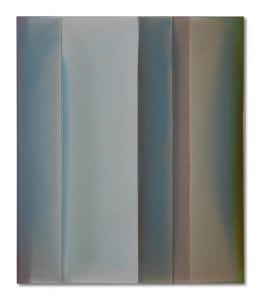

Working on a flat surface, English uses tape to help create a pool of paint; the tape is then peeled off. “I pour polymer that’s tinted with paint, sometimes making many, many layers of it,” she explains. Over six years in working with this method, English has learned about the material and what colors she can produce with it. Somewhere along the way, English realized that the shapes she was “pouring” were similar to the hourglass shapes she had painted, decades earlier, in graduate school. She had already returned, earlier in her professional career, to these same shapes. “I took a break then took off where I left off,” she explains, continuing, “I made an abstract image, then put it away and seven years later found it and went back to it: the hourglass stretched and torqued.”

Finding the cutting and shaping of large pieces to be very time consuming, and getting far greater enjoyment from the pouring component of her process, English shifted away from the shapes, but continued the pouring process, this time working with “almost squares” of 11 x 11.5 inches. After a period of time with these, experimentation entered again, and she cut the almost-squares into quarters, turned them vertically, and started putting them together, finding the edges “created a way of achieving subtle variations in tone, reflecting landscapes that I hold in my memory and things I see in the world.”

Exhibition notes describe English’s paintings as having “an unusually rich surface texture and color, which is created by pouring layers of tinted polymer on panels. The poured polymer mimics nature: a layer of paint hardens like ice or mud, its thickness and viscosity impacting how the surface dries. Within the surface are small inconsistencies that are like drawings; paint collects and coagulates and cracks are formed. These marks are the result of the process of pouring and letting layers of paint dry, and English embraces the delicate relationship between control and accident.”

English started putting together long sequences of these small blocks, setting them up on a track upon which she could then shift them around, as moveable parts. “The number of choices was staggering.”

Altering the direction again reduced the possibilities, which suited English better. “To limit choices is important for me,” she says, noting, I play with orientation continuously. Turning something you’ve done one way to another is a radical change. For me the vertical is about narrative; they’re sequences; I think I was thinking about endings.”

With her most recent work, some displayed at Matteawan and others at the Littlejohn Gallery in Manhattan, English wanted to continue pouring sequences, in a vertical format. To consider color, she worked first in watercolors, applying the paint directly, as opposed to the earlier pouring, which is much more speculative. “You can’t see what it looks like for 24 hours, until it dries. There’s a relationship between control and accidents and accidents lead you to discover things. Over the years I’ve gotten more and more precise in making the colors; they’ve become extremely specific.” English started cutting the watercolors up, making ‘ exact thirds’ collages of them. These watercolor collages are also on view at Matteawan.

English, who, along with her husband, John Harms, has long had a “day job” doing specialty painting, under the company name of English & Harms. She used to feel that there was no relationship between that work and her own painting. “I didn’t mind doing it, but over the years in fact I’ve realized how connected they are, because they are both totally visual things: I think about color, environment, space, materials, tools — something will occur in that world that I’d bring in to this one.”

At this “mid-career” juncture of her working life as an artist, English feels she is in “a sweet spot, right now.” With two sons in their twenties, “it’s affording me time to do my work. It’s headspace things too. Having a dedicated studio has always helped. I don’t bring my computer and for a long time there was no internet. If something’s in progress I step right into it. I haven’t always been able to afford the studio, but somehow I coughed it up … I combined working with having children, always working and showing my work, but there was always a beginning and end to the time I could paint — there were always increments, like there would be two hours free and I would always imagine what it would be like to have eight hours, imagined what it would be like to lose track of time. Our culture is all about the badge of busy-ness. For an artist, just floating is important.

English’s work has been previously included in Matteawan Gallery exhibitions Elemental in 2014 and The UV Portfolio in 2013. Her work has been the subject of solo exhibitions at Littlejohn Contemporary, NYC; Theo Ganz Studio, Van Brunt Gallery, Beacon; and Concrete Gallery, Cold Spring. Group exhibitions include Abstraction: New Modernism at Ann Street Gallery in Newburgh, in 2013; Currents: Contemporary Abstract Art in the Hudson Valley at the Edward Hopper House Gallery in Nyack, in 2012; and Far and Wide at the Woodstock Artists Association and Museum in Woodstock, in 2012. In September 2016 English will be participating in an artist residency at Saltonstall Foundation for the Arts in Ithaca. She received an MFA from Hunter College and a BA from Hamilton College.

Pourous Light runs through Aug. 21. Matteawan Gallery is located at 436 Main St., Beacon. Summer hours are Friday, Saturday and Sunday noon – 5 p.m., and by appointment. For more information visit matteawan.com and susanenglish.us or phone 845-440-7901.