Philipstown resident, pioneer in off-the-wall comedy, helps relaunch humor magazine

It was summer in New York City in 1988 and Brian McConnachie was living an enviable life for a 45-year-old writer. He and his wife Ann were renting a duplex on the top two floors of a handsome brownstone on West 78th Street.

An advertising man in his younger days, McConnachie had made the giddy leap to National Lampoon, which led to writing for NBC’s Saturday Night Live, where he became one of the pioneers blasting open the politically charged, gonzo comedy landscape in the late 1970s and 1980s. With the birth of his daughter, he started writing episodes of children’s shows such as Noddy and Shining Time Station. And his landlord was offering to sell him that sweet apartment.

Another New York City winter was approaching, however, with fuel prices high enough to keep a guy awake at night.

“We’d heard there were good schools in Garrison,” McConnachie recalls. They bought an 1890s farmhouse with a one-horse stable.

He’d never lived anyplace like Garrison. “The first day of school, we walked our daughter down this old ox-cart road, and horses were grazing,” he says. “It reached the point where I thought, ‘Oh, come on. Let’s tone down the Norman Rockwell.’ ”

Before he knew it, McConnachie was part of the picture. He put up a fence and started planting, driven by his “inner farmer.” Other countrified chestnuts followed: Coaching Little League; staging a variety show at the St. Philip’s parish hall; writing and producing a musical at the Depot Theater. (Meanwhile, Ann ran Gov. George Pataki’s office in New York City from 1995 to 2006.)

McConnachie also continued to write comedy and act. He’s had minor roles in seven Woody Allen films as well as classic comedies such as Caddyshack and Sleepless in Seattle.

McConnachie, 74, who now lives in a cozy house with lots of wood and stone in Cold Spring, has a new escapade. The American Bystander is a quarterly revival of a humor magazine he founded and edited in 1983 of the same name. He filled it by asking writers he knew to send him their “bottom-drawer” material, such as “scripts, short stories, parts of novels and whatnot.”

The revived title, called “essential reading for comedy nerds” by The New York Times, is now on its fourth issue (see americanbystander.org). Each is funded by online fundraising and assembled with his co-editor, Michael Gerber, a writer who recruited McConnachie for the relaunch. The magazine is a gorgeous throwback to a pre-internet age — its content is not available online — and stuffed with pieces, cartoons and artwork by humorists committed to reclaiming territory lost to the tin whistle of Twitter.

McConnachie’s dry, offbeat wit is evident in his piece in Issue 2, “The Ding-Dong Hoodlum Priest,” about a kid named Danny whose dream is to be “a bra salesman, or a bra designer. Basically bra-related work.” A cop tells him, “The bra biz is a sucker’s game, Danny.” So Danny becomes first a middleweight boxing champ and then a priest. Which causes problems when the church bell tower gongs during communion and “Father Dan punched Mrs. Rodriguez in the mouth.”

McConnachie grew up in Forest Hills, Queens. His dad was a newspaperman who was pals with Jackie Gleason; his mom read him James Thurber. “When dad needed extra money, he’d go to the Athletic Club and play gin,” said McConnachie.

The day McConnachie knew that nothing made him happier than comedy occurred while he was with his best friend, Jack Ziegler. They were 10 or 11, hunting down comic books in a store near the Port Authority. “I’m on my hands and knees, looking at these issues in the bottom of this rack,” he said. “And for some reason, I looked up at the ceiling. And there was a sign on the ceiling that read, ‘What the hell are you looking up here for?’ I burst out laughing.” (Ziegler, who died this year, would go on to become a cartoonist for The New Yorker.)

McConnachie’s father sent him to LaSalle Military Academy on Long Island, and from there he attended the University of Dublin before moving to New York. He loved a new magazine called National Lampoon and began submitting cartoons while working at a restaurant on 72nd Street. Soon after, one of the co-founders, Henry Beard, came by to offer him a job.

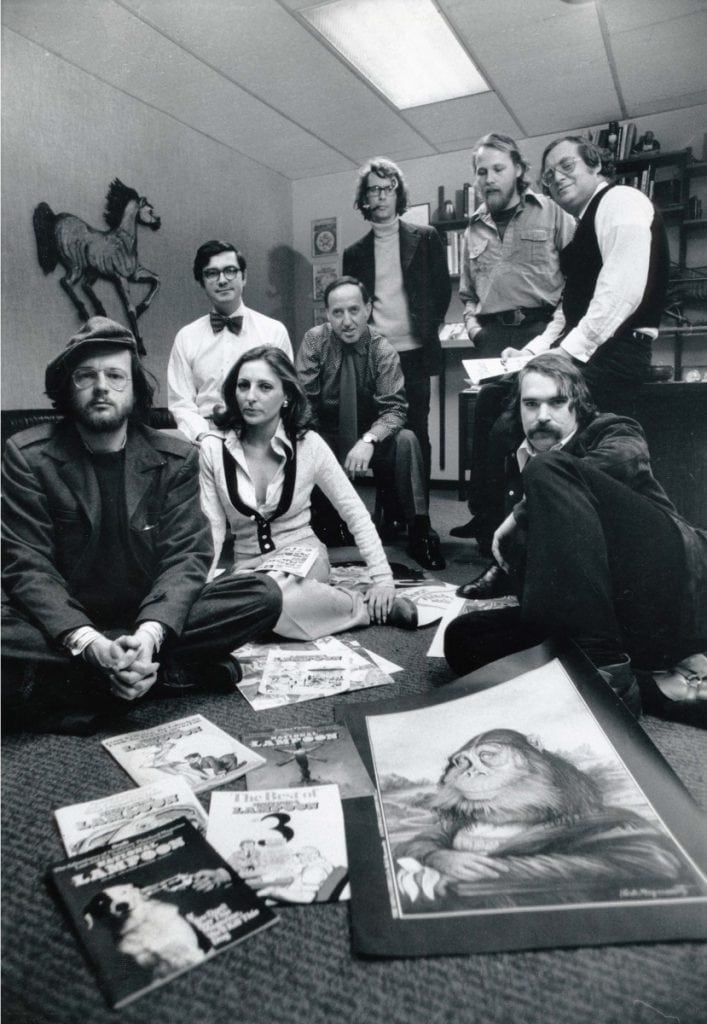

In his seersucker suit, bow tie and 6’4” frame, McConnachie stood out among the longhairs at the Lampoon. But only on the outside. In Drunk Stoned Brilliant Dead, a history of the magazine, Rick Meyerowitz wrote of McConnachie: “He emphasized the illogical and the absurd, and he demolished the reader’s cozy expectations. He quickly became every other writer’s favorite writer.” He added that McConnachie’s work for the Lampoon “is well loved, here on Earth, and on his home planet.”

Another history of the Lampoon noted that “behind a horn-rimmed exterior lay profound eccentricity.” He preferred the “zany over the scathing,” it noted, creating comics such as Amish in Space and The Attack of the Sizeable Beasts, in which large squirrels overran a town. He also wrote Tell Debbie, an advice column with responses such as “How very unfortunate.”

Within a year, the magazine was so popular that it launched a radio show and a stage show. To populate both, the company brought in John Belushi, Gilda Radner and Bill Murray from SCTV. McConnaghie and Belushi became close, reminiscent of his father’s friendship with Gleason.

In 1975 Lorne Michaels launched Saturday Night Live. Soon after, the show’s head writer, Michael O’Donoghue, called his friend McConnachie to report that the show was stealing from him.

“There was a Lampoon piece I did — it was a cartoon of a police lineup of a duck, a refrigerator, a nun and a black man. And a woman is pointing to the black man: ‘He’s the one who did it,’ ” McConnachie recalls. “And they did it as a sketch on the show, with Richard Pryor playing the black man. How that played out was Lorne saying to me, ‘Well, we’ve been using your stuff. We might as well hire you.’ ” (In 2013, after a similar incident with a joke purloined by The Simpsons, McConnachie was invited to write an episode.)

At SNL, McConnachie says, “your job became to get your piece on the air,” no matter how abstract the idea.

“Sometimes a title would come to me before I knew what the sketch was going to be,” he recalls. “That happened with Name the Bats. The piece was a game show and Belushi and Gilda are the contestants. They’re locked inside a barn and the host hits the wall with a baseball bat, which gets all the bats swarming around inside, and Belushi says, ‘I found a fruit bat. I found a fruit bat!’ and the hosts say, ‘No, no, no. Don’t tell us what kind of bats they are. We know what kind of bats they are. Who do you think put them in there? No. Give them names!’ So then they just went comatose by the end.

“Another one that just came to me was from the title Cochise at Oxford. They were in this classroom, Eric Idle [of Monty Python] is the teacher, and it’s jokes on top of jokes and the banter is fast. One of the students is Bill Murray dressed as Cochise, the Apache chief. And Eric Idle is doing an imitation of hopping away from a puddle of urine: ‘You mean like this?’ And he tucks one leg up and hops away from the imaginary pool of urine. And a hatchet comes right in front of him. They placed it perfectly. And then he slowly turns around and he says, ” ‘All right. Who threw that?’ ”

Fighting Atop the Train

You’d think they go into the parlor car to slug it out, unless it was the people in the parlor car who told the brawlers to take it outside and up a flight.

~ From a 2015 piece by McConnachie for National Public Radio called Before Fighting Atop a Train, Some Things to Consider

“Lorne didn’t like the piece because he didn’t understand it — it’s understandable that he didn’t understand it,” McConnachie recalls. “But Belushi said to Lorne, ‘Unless we do this piece, I’m leaving the show.’ ”

The sketch ran. “Al Franken, to his credit — because he was on Lorne’s side about the sketch — came up to me afterward and said, ‘You know, now I see what you were driving at. I didn’t see it before.’ Which I thought was awfully generous of him.”

The bond between McConnachie and Belushi lasted until the comedian’s death in 1982 of a cocaine and heroin overdose at age 33. “Belushi would tell me and everyone on the show, ‘If something happens to me, I want you to look after [my wife] Judy.’ And if you hear that enough times, it’s a matter of when,” said McConnachie. “Toward the end I was getting more and more phone calls from him.”

These days when the winter comes, Brian and Ann head to Osprey, Florida, “formally the winter home of the Ringling Brothers circus,” notes Brian. “The ringmaster once fixed our plumbing.” Notable residents include John Gotti Jr. and Steven King. “It’s the dangerous end of the Key.”

Spring finds the couple back in Cold Spring. “I love the Memorial Day Parade,” Brian says. “I get teary. Maybe it has to do with the firefighters and high school bands. It has a wonderful charm. I saw one, they were playing, ‘I talk to the trees, but they don’t listen to me,’ from — what was that? Well, whatever. It was just so sweet and just off-key enough that it’s endearing; they’re not pros, they’re heartfelt amateurs. It was perfect.”

In April 1983, McConnachie appeared on Late Night with David Letterman to promote his new magazine, The American Bystander.