From bombs to birds at former military base

By Michael Turton

You can’t just show up for a tour of Iona Island, located south of the Bear Mountain Bridge. The only person allowed to take anyone around the place, which is closed to the public, is naturalist Donald “Doc” Bayne, who has explored and studied its 125 acres for more than 20 years and is known as “the mayor of Iona Island.”

Bayne conducts three-hour tours six to eight times a year between May and October. Call 845-786-2701 to inquire.

The island, now a wildlife sanctuary and part of Bear Mountain State Park, has played a role in every chapter of Hudson River history, including during World War I, which the U.S. entered a century ago, in 1917. In its earlier days it was home to Native American encampments and Dutch settlers, supported vineyards and orchards and was a training ground for a champion boxer. It may even have been trod upon by dinosaurs.

An island at war

During the American Revolution, Iona Island was occupied by British troops. Its U.S. military history began in 1899 when the Navy purchased the property to store munitions. The government constructed 164 buildings, including a hospital, firehouse, barracks, officers’ quarters, icehouse, shell and powder buildings and storage bunkers. Locomotives circled the island, powered by compressed air.

Four machine gun nests and an antiaircraft gun defended the enclave, and 100 Marines patrolled its shores.

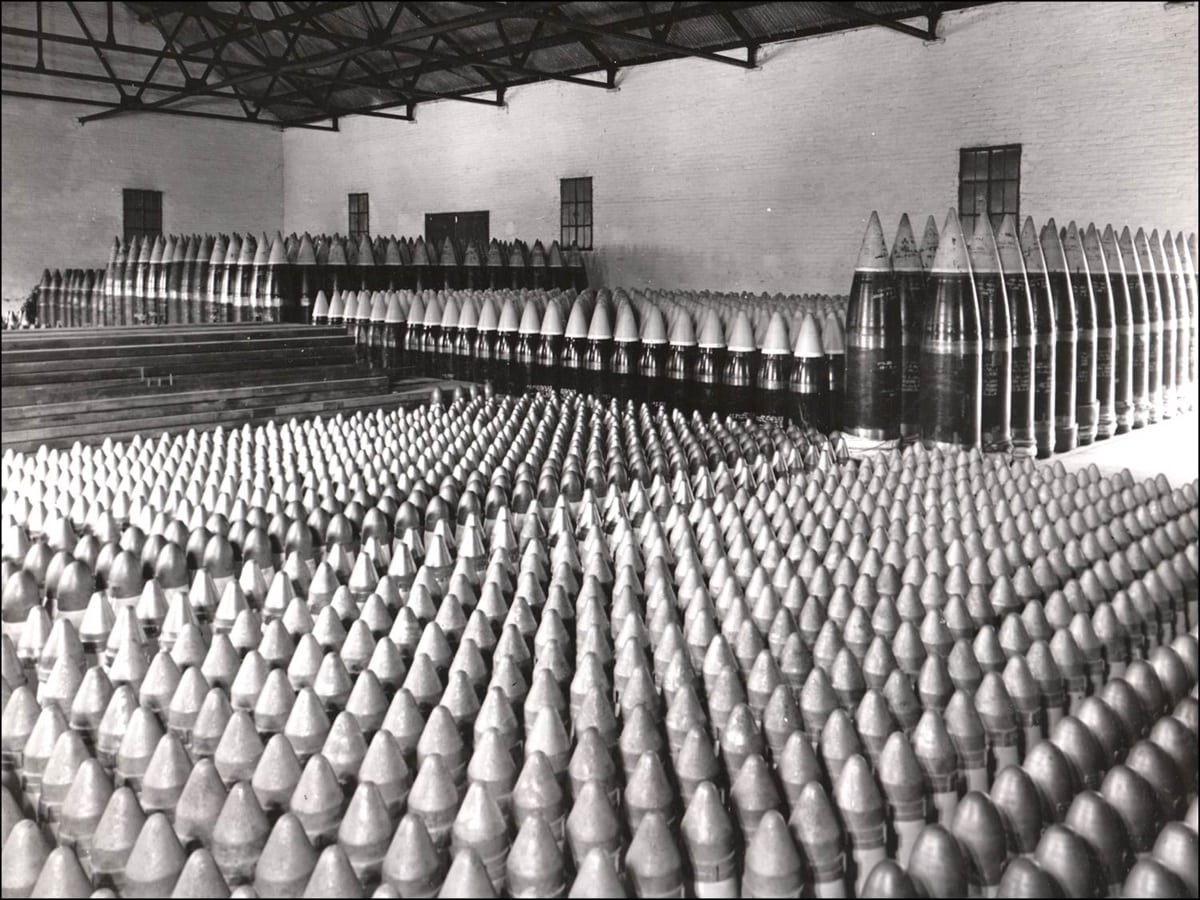

Because high explosives could not be stored in New York City, the Navy shipped them to Iona Island on barges to be placed in “shell houses,” Bayne says. “The fuse was taken off the top and sample powder tested in another building to ensure it was explosive enough.”

On Nov 5, 1903, workers had trouble removing a fuse and forced the issue using a wrench. The shell exploded, setting off thousands of others. Six men were killed and almost every building damaged or destroyed.

Submarines on the Hudson

During World War II, submarines came to the island (the water is 100 feet deep at that point in the river) to be armed with torpedoes. In 1942 the Navy purchased nearby Round Island, where a private quarry had provided stone for the Brooklyn Bridge.

The Navy built 20 bunkers at the south end of Round Island, one of which survives. At low tide a footpath leads from one island to the other. The Navy closed Iona Island as a munitions depot in 1947.

Dinosaurs?

In 1972, fossilized coelophysis tracks dating to 200 million years ago were discovered in Blauvelt, a few miles south. “It’s the same kind of terrain and very close,” notes Bayne. “Why not here?”

Five thousand years ago Iona Island was home to members of the Delaware Indian tribe drawn by its plentiful food.

“There was lots of striped bass, sturgeon, crab, shell fish” and oysters weighing up to seven pounds, Bayne says. Early inhabitants used the rock shelters as dwellings. Today, the Trailside Museum at Bear Mountain has a clay pot and other artifacts from the encampments.

In 1683 the Dutch purchased the island from its Native American inhabitants and began cutting trees and building houses. Foundations are still visible on the north end and there are a dozen on Round Island. “At that time the Dutch put their animal pens inside their houses,” Bayne says.

Then known as Salisbury Island, Iona was sold to John Beveridge in 1847, who gave it to his son-in-law, Dr. E.W. Grant, who changed the name to Beveridge Island. Grant planted 20 acres of grapes and 2,000 fruit trees. Unfortunately, people didn’t like the bitter “Iona grapes,” Bayne says.

(Bayne says newspaper accounts claim the name “Iona” was a send-up of Grant, who attended horticulture meetings in New York City and had a habit of introducing himself by saying, “I own an island…”)

After the banks foreclosed on the vineyard and fruit operation, investors turned the island into a playground. Steamers brought visitors from the city by the hundreds. The entertainment included a merry-go-round.

“It was such a popular destination they say that you couldn’t walk more than 10 feet on weekends without stepping on a blanket,” Bayne says. John L. Sullivan, the first heavyweight champion of gloved boxing, trained there on occasion.

After the wars

When the state parks system bought the island from the Navy in 1965, the plan was to convert the barracks into a Hudson Valley Museum. A bowling alley, swimming pool and playing fields were also proposed. It never happened, and in 1980 vandals destroyed the barracks.

Bayne says he was initially upset that the island was never developed but now sees the silver lining. “It’s back to what it was like when the Native Americans were here,” he says. “There’s milkweed everywhere,” along with butterflies, deer, bear, coyote, fox, rabbits, wild turkeys and eagles.

Even Bayne, the caretaker, isn’t always welcome. Recently, at the entrance to the bunker, a coyote whose four cubs were inside came out growling. “I wound up on top of the door,” Bayne says. “I still don’t know how I got there.”

Historical photos courtesy Doc Bayne