Treatment center works to end deceit, work on hope

Treatment center works to end deceit, work on hope

By Liz Schevtchuk Armstrong

The pervasive grip of opiates comes as no surprise to Arlene Seymour. In more than two decades as a counselor, she has confronted drug abuse, the shame attached to it and the lying the shame produces.

But she also knows the grip can be broken.

At the CoveCare Center, which is designed to provide a “safe space” for addicts, Seymour manages the clinic and treatment programs. She also oversees outreach to schools, including Haldane in Cold Spring. She began her career as an intern at St. Christopher’s Inn in Garrison and, before joining CoveCare, worked for years at the Lexington Recovery Center in Beacon, which has since relocated to Wappingers Falls.

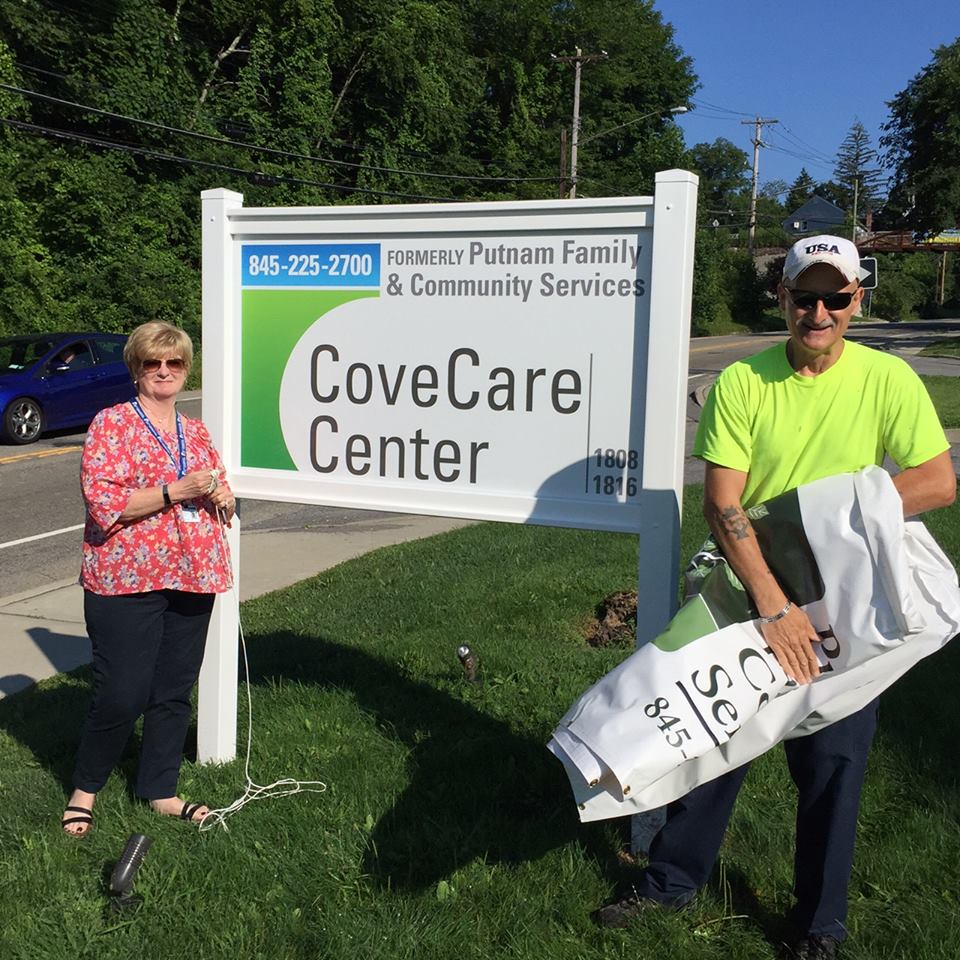

Based in Carmel, CoveCare’s medical staff provides counseling and medications to addicts, including inmates at the Putnam County jail. Established in 1997 as Putnam Family & Community Services, the nonprofit changed its name this year in part because of a misperception it was a county agency, Seymour says.

Last year CoveCare served 241 patients in its substance-abuse programs, plus another 178 in a rehabilitation program for those with drug or alcohol problems or serious mental-health issues, or both.

The rise of opioids

Over the last 20 years, Seymour says, opioids have taken over, and cocaine use has diminished but not disappeared. Two patients tested positive for cocaine in a single week in August, she says.

Alcohol abuse continues but nicotine addiction has decreased significantly, she says, following years of public campaigns against smoking. At the same time, she says, attitudes about smoking marijuana have become more lenient. The problem is, the weed on the street is far more potent than what was available in the 1960s, she says, both in strength and what might be added to it.

Still, opioid abuse claims most of the public’s attention, as the toll of victims climbs. Seymour, who attended an Aug. 31 candlelight vigil in Cold Spring to remember those who have overdosed, noted “it’s mostly boys” who die, perhaps because they are more likely to engage in risky behavior.

The rate of brain development may also play a role. “In your 20s, you go through a stage when you actually understand what a consequence is, a cause and effect, and your brain matures to accept that,” she says. “Boys mature later than girls, so that could have something to do with this.”

In addition, alcohol and marijuana use can slow brain development in young people, she says. “A young addict will think, ‘I can use one more time; it’s not going to happen to me,’ ” Seymour says.

The longtime counselor says one consistent characteristic of addicts is deceit. “I expect people to lie to me,” she says. “I’ve been doing this for so long, I just don’t trust what someone who’s addicted says.”

That goes for those who seemed to be on the right path but relapse. “You can kind of tell when people are using again, when they’re telling you little stories,” she says. “They lie to themselves. It’s the shame that keeps the lying going.”

By contrast, those who are able to stay off drugs “usually are pretty honest,” she adds. “Life has changed. They don’t have that shame.”

The age of addiction

While young people typically overdose on heroin, patients age 50 and older are taking pills. Lately, Seymour says, she’s been seeing more patients in their 60s — enough that CoveCare runs free “senior” programs for clients in middle age or older.

For older clients, the risk of addiction or overdose is enhanced, she says, because the body becomes more “finely tuned” as it ages and because people tend to take more medication. Combined, drugs “can have a synergistic effect — the effect of two are greater than the effect of either one alone.” For that reason, doctors “need to be more sensitive to what prescriptions are doing” with older patients.

For a young person suffering from addiction, “families are the key to helping them get better,” Seymour says, but finding residential treatment for adolescents can be difficult. “There aren’t that many facilities that are good” and although insurance coverage has gotten better, long-term care can still be an economic hardship.

Seymour said her youngest client was 13; state regulations prevent outpatient centers like CoveCare from treating anyone younger than that. But its staff does reach out to students. As part of its schools program, Seymour and other counselors talk to children as young as kindergarten and first grade.

“We tell them it’s about making good choices, and feeling empowered, and not feeling bullied, and being able to say ‘no’ if you really mean ‘no’ and picking your friends” wisely, she says. “It’s about behaviors” early in life, “because behaviors clearly influence your choices later on.”