Climate change will bring heavy rain, but where will it go?

Climate change will bring heavy rain, but where will it go?

By Michael Turton

Much of the conversation surrounding the effect of climate change on water focuses on flooding caused by sea-level rise and extreme storms. But another, less talked about, aspect of the problem is how to get all that water back to the river.

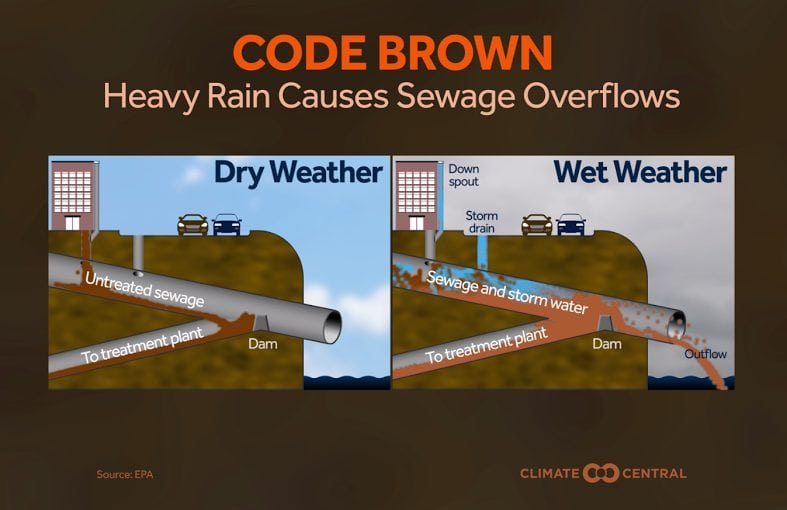

Stormwater, or rain that is not absorbed, flows into streams that lead to the Hudson. If the number and severity of storms increase as climate change models suggest, stormwater runoff is bound to increase as well, adding to the risk of flooding and a phenomenon known as “combined sewer overflow” in which the heavy rains overwhelm treatment plants. To avoid having sewage back up into homes when that happens, it’s released into the river.

Bryan Quinn, a Beacon-based environmental designer, says we should be thinking more about stormwater, including using less impermeable concrete and asphalt. We also should be thinking small, he says.

“The DEC [state Department of Environmental Conservation] has really upped their game in the past couple of decades regarding stormwater management for new developments,” he says. “But for smaller projects they haven’t gone far enough.”

Quinn advocates rain gardens and planting depressions or bio-swales which slowly release water over time. The vegetation they contain not only helps to reduce flooding, it filters pollutants. Retention ponds and rain barrels have similar effects.

He’s not a fan of manicured lawns. “If we can replace lawns with meadow, it can do a lot to increase infiltration and reduce water flows.” In more rural areas lawns can be replaced by forest.

Jennifer Zwarich, who heads Cold Spring’s Tree Advisory Board, also sees forests as part of the solution. “The trees in our community forest are on the front line of our region’s struggle with stormwater management,” she says. “Tree canopies and root systems significantly slow down runoff by capturing water and absorbing or releasing it back into the atmosphere.”

Safe Harbors Green in Newburgh was designed by Quinn and incorporates his conservation concepts (see video below). Plant materials and swales help the small park absorb all the rainfall it receives. “Not a single drop leaves this park,” Quinn says. His design also accounts for climate change by including an extra, deeper swale that will slowly release water in the event of an extended downpour.

Quinn says there must be more collaboration between municipalities so that they together can manage an entire watershed, rather than only the parts within their borders. “Political boundaries don’t make any sense from a water perspective,” he says. Philipstown’s Clove Creek for example, flows south along Route 301 in Putnam County before heading north along Route 9 into Dutchess County and the Town of Fishkill, then west through Beacon before emptying into Fishkill Creek.

In this video by Gregory Gunder that we posted in September 2017, Bryan Quinn explains the concepts behind Safe Harbors Green.

Other stories in Part 2: