Mapping tool says we’re more than halfway there for the region

Mapping tool says we’re more than halfway there for the region

By Jeff Simms

The Hudson Highlands — with its steep slopes, marshy wetlands, valleys and ravines — represent the type of complex landscape that conservationists are seeking when it comes to protecting wildlife habitat, especially in the era of rapid climate change.

Diversity is a key characteristic of “resilient landscapes,” a term first used by The Nature Conservancy about a decade ago to describe the wildlife habitat most suited to endure the rapidly changing climate.

The two main characteristics of resilient lands are complexity — an assortment of “microclimates” that create a range of temperature and moisture options for species — and connectedness, which supports the continued rearrangement of species as they respond to global warming.

The thinking, says Nava Tabak, director of science, climate and stewardship for Scenic Hudson, a nonprofit environmental group, is that it’s hard to predict where species will end up as their ranges shift.

“The best we can do is conserve a diverse landscape,” she says, “and the Highlands is one of those places.”

Clarence Fahnestock and Hudson Highlands state parks score high for resiliency, which is one reason why conservation organizations have consistently acquired and added lands to these swaths.

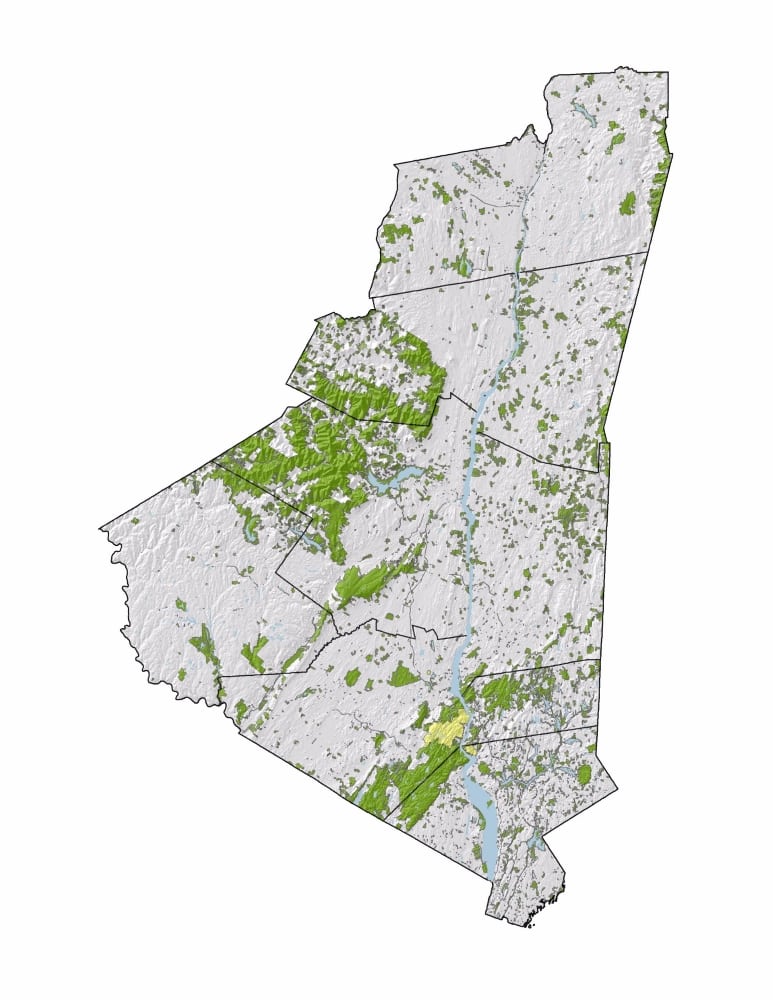

In 2016, Scenic Hudson introduced the Hudson Valley Conservation Strategy, a mapping tool that identifies the most “efficient” conservation projects to preserve biodiversity, resilience and connectivity.

“This doesn’t give you marching orders to go out and get this or that property,” Tabak says, “but it shows us important areas where there are opportunities.”

In the 11-county Hudson Valley region, almost 900,000 acres have been protected by the state and private organizations such as Scenic Hudson, including the 6,000-acre Hudson Highlands State Park Preserve between Cold Spring and Beacon that provides habitat for bald eagles, black bears and timber rattlesnakes, among many other species.

On the other side of the Hudson, thousands of acres — Harriman, Bear Mountain and Storm King state parks — protect a major spring and fall flyway for migratory birds.

It’s impossible to predict exactly how much more land needs to be conserved, but Scenic Hudson’s tool suggests 750,000 more acres in the 11 counties would “give us a pretty good portfolio of places that would enable species to adapt with climate change,” Tabak says.

That’s a tall order, “but it’s not out of the realm of possibility,” she says. “It’s something to strive for.”

Into the Wild

Wrenches in the System

Saying Goodbye

Could Trees Save Us?

So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish

The Climate for Lyme