Master the game of bridge and you may never look back

By Alison Rooney

If anyone in Beacon is close to being recognized as a “bridge whisperer,” it would be Neal Christensen.

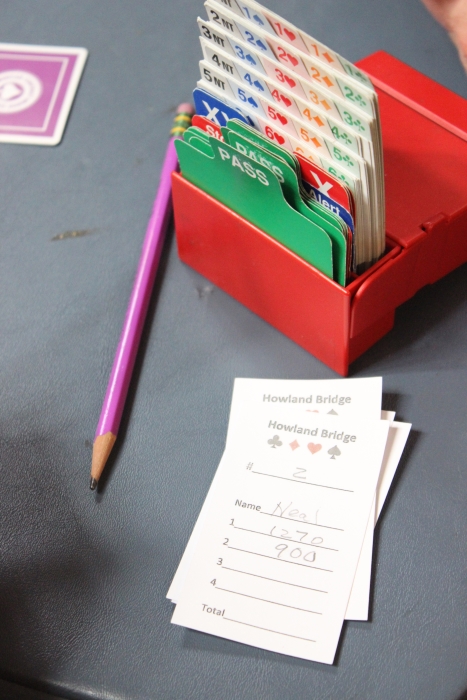

The retired IBM engineer and former faculty member at Mount St. Mary’s College is a regular at the Monday morning bridge gatherings at the Howland Cultural Center that have been going on for some 20 years. At a recent session, as players changed tables, many drifted over to Christensen, showing him their hands, seeking advice. The questions and his answers, as well as the conversation around his table, were foreign to anyone but bridge players:

“My partner opened with a club. Should I?”

“You should have played the king right away.”

“I’m stuck with one no trump.”

“I’ve got a balanced hand.”

“Discretion says I should bail. I hate to bail. But I will.”

“I’m a little overbid. Glad I passed.”

Ay caramba!”

Christensen’s enthusiasm for the game is evident. “Bridge is the most complex card game in the world,” he says. “It involves using logic and understanding probability. It’s a game of partnership, built from communication and trust. The communication is all done through the cards.”

Other players at a recent Monday session often used the word “addictive” to describe the game’s appeal. The consensus was that once you got bitten by the bridge bug — you stay bitten.

Aspects of the game date to the 16th century, at least, and the first published rules of biritch, or Russian whist, from which the name bridge is thought to have evolved, appeared in the 1880s. It became popular in the U.S. and England a decade later as “bridge-whist.” More fine tuning, particularly in bidding and scoring, followed, until the arrival of “contract bridge” in 1925.

Nowadays the most popular form of bridge, and the type played at the Howland Center, is duplicate bridge, in which the same arrangement of the 52 cards into the four hands is played at each table and scoring is based on relative performance. The importance of skill is heightened while that of chance is reduced.

Bridge reached its zenith in the U.S. in the 1940s and 1950s, when “it was as popular as baseball,” Christensen says. Today it’s a challenge to get young people to take it up — although Kathie Munsie, who has been coordinating the Howland group for the past five years, says she has made inroads with her 11-year-old grandson.

At the Howland, players change partners every four hands, which “encourages camaraderie and the benefits gained from the sharing of knowledge,” Munsie explains. Players come from Beacon, Cold Spring, Fishkill, Newburgh, Pleasant Valley, Poughkeepsie and Wappingers Falls.

Christensen learned the game from his wife Suzanne years ago but took a 30-year hiatus when their son was born. Now he’s back at it with a vengeance. He considers bidding the game’s most difficult aspect.

“Each bid is intended to communicate information about your hand to your partner, and that can be hard to do,” he says. It’s easier for those who think in certain ways. “A rational brain is better suited for bridge than an artsy one. Memory is important. You have to count cards, keep track of the four suits. Know what trump cards are still out there.” Suzanne Christensen adds that bridge is hard to teach, “because you have to learn it all at once; it’s not progressive.”

Join the Club

Even if they are perplexed by the more challenging game play, many new players quickly become converts. Harry Norman, who began playing 18 months ago, notes there is a “steep learning curve, but if you stick with it you’ll start making breakthroughs. I especially like this group; other groups discourage socializing, but this group is very congenial.”

Rose Clary-Droge hadn’t played since her youth but was encouraged by a friend. “I took lessons from Neal,” she says. “Although I remembered a lot, there were all these new rules. Now, it’s like, ‘Don’t disrupt my bridge day!’ ”

Eldon Smith began about two years ago and says he has fallen for the game hard. “My mother was great at it, but I was always too busy to learn,” he recalls. “Now I have the time and willingness. And I’m learning more each time. I went to a place in the beginning, where, well, they didn’t throw me out, but they did suggest I come back after taking lessons. I play several times a week, here and at Lagrangeville. I can get bridged out.”