Haldane, Garrison and Beacon, like most districts in New York, are told each

year by the state how much they can raise taxes. How is the cap calculated?

The inflation rate of 5 percent has made it a challenge to balance 2023-24 school budgets because of a state-imposed cap that limits property tax levy increases to 2 percent or the rate of inflation, whichever is less.

To calculate how much they can raise taxes, most districts in the state, including Haldane, Garrison and Beacon, each year must use a state-mandated formula with as many as a dozen factors.

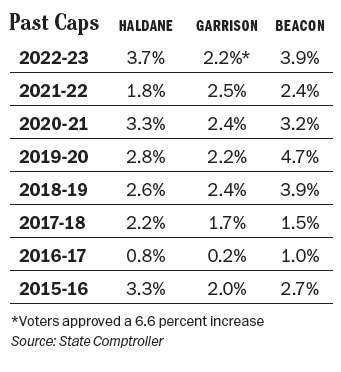

The vast majority of the school caps this year are clustered around a median of 3 percent, said Brian Fessler, governmental relations director for the New York State School Boards Association. (A district can override its cap, as Garrison did last year, but it requires approval by 60 percent of voters.)

To explain the formula, we’ll use Garrison as an example, with assistance from Joseph Jimick, the business administrator for the Garrison district, and representatives from the state comptroller and Department of Taxation and Finance.

First, it’s not really a 2 percent cap.

It starts at 2 percent, but a number of factors in the formula drive the cap up or down for each district. That’s why Garrison’s cap is 3.29 percent while Haldane’s is 1.96 percent and Beacon’s is 3.64. As we’ll see, the 2 percent cap established by law plays a major role in holding down property tax increases.

Everything starts with the previous levy.

The cap formula determines the maximum increase a district can make in the property taxes it collects over the previous year. In Garrison, the levy for 2022-23 was $10.38 million.

The formula allows this number to be adjusted if a district collected too much or too little. But Garrison was on target, so the $10.38 million is where we begin.

How much did the assessed value of property grow?

School districts raise money by taxing the assessed valuation of property in the community. Each year, the comptroller tells districts how much that changed by providing what is known as a “tax-base growth factor.”

For Garrison, the growth factor was 1.0024. That means that the comptroller’s office believes Garrison’s overall property value assessment grew by less than 3/10 of 1 percent last year. How did the comptroller get that number? It relies on assessment figures from the Department of Taxation and Finance.

But doesn’t 3/10 of 1 percent seem too low? Isn’t the value of property in Garrison rising faster than that? Maybe. But the comptroller is not measuring market value. He’s measuring the value of property as determined by the local assessor, not real-estate agents or sales. (By comparison, in Beacon, which has seen a spurt of new residential construction, this year’s growth factor is 1.0163.)

Garrison’s tax-base growth factor means it can only raise its tax levy in 2023-24 by about $25,000, before adjustments.

Subtract last year’s capital levy.

Every district can collect taxes for capital improvements, but the spending must be approved by voters separately from the annual budget. Because capital levies are not included in the tax-cap calculation, you must remove them from the previous year’s levy before calculating the cap.

In Garrison, the capital levy for 2022-23 was $586,991. This is the money that the school spent on HVAC systems, the removal of asbestos floor tiles, security cameras, phone systems, door locks and monitoring of doors. After subtracting the capital levy, the base becomes $9.82 million.

The Effect of the Cap

The New York State tax cap went into effect in 2012. It applies to most public school districts and local governments, including counties, cities, towns, villages and fire districts.

According to a 2019 analysis of state data by the Rockefeller Institute of Government, the average school tax levy in the Mid-Hudson Valley has dropped 75 percent since 2004. It was 7.59 percent from 2004-07 (the highest of any region), 3.31 percent during the Great Recession (2008-11) and 1.88 percent since.

Since 2004, Haldane’s average has fallen from 7.8 percent to 2 percent; Beacon’s from 6.9 percent to 2.6 percent; and Garrison’s from 4 percent to 1.8 percent.

The study estimated that Mid-Hudson homeowners have paid $5.6 billion less in school taxes since the cap went into effect.

Add payments in lieu of taxes.

Some districts grant tax breaks to businesses to entice them to create jobs or provide other benefits to the community. For example, the Beacon City Council recently approved a PILOT agreement with an affordable housing developer that will pay an incrementally increasing fee to the school district over the next 40 years rather than assessment-based payments.

These PILOT payments are considered part of the tax base from the previous year so they’re supposed to be added into the mix. But Garrison has relatively little commercial and industrial property and no PILOT agreements.

Here is where the 2 percent cap comes in.

We have reached the point where “2 percent or the rate of inflation, whichever is less” is applied.

The current rate of inflation is about 5 percent, which means districts must cap the growth at 2 percent. Each year, the comptroller converts the inflation rate into the “allowable growth factor” that applies to every district. If inflation is more than 2 percent, the allowable growth factor, by law, must be 1.02 percent. If it is below 2 percent, the growth factor will essentially be the rate of inflation.

For Garrison, we multiply $9.82 million by 1.02 and get $10.01 million.

Put back the capital levy.

We subtracted the 2022-23 capital levy to determine the levy applicable to the 2 percent cap. Now we have to add the capital levy back to get a final cap number.

In Garrison’s case, the capital tax levy for 2023-24 is expected to be $706,747. This spending was authorized by Garrison taxpayers as part of a referendum in 2019, and under that authorization the district has borrowed $8.3 million that is payable over 15 years.

Once you add the capital levy back, you get $10.72 million.

Getting to the final cap.

There are other factors that can be added to the levy, such as costs of legal judgments and costs associated with pension funds, but Garrison doesn’t have those.

So the final allowable levy is $10,721,026, or 3.29 percent more than the 2022-23 levy. That’s the maximum cap.

Next week: Is Garrison’s squeeze an early warning sign for other districts?

If properties in Garrison were correctly assessed, you would have a lot more money in the pot. Why wasn’t the Lakeland Central School District mentioned in this article? Hundreds of families live in Philipstown in the Lakeland District but are never included in school district discussions.