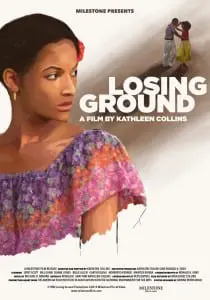

Downing screens film restored by Philipstown’s Nina Lorez Collins

By Alison Rooney

The journey that Nina Lorez Collins has taken is akin to opening up a treasure chest stored for decades in an attic and discovering something hazily remembered, then bringing it downstairs for others to rediscover as well — only on an unexpectedly grander scale, with several reels of film. Those reels, unremarkable in form yet remarkable in content, contain a film, Losing Ground, written and directed by her late mother, Kathleen Collins. The story of how she brought her mother’s film back to a very invigorated life could almost be called cinematic.

Kathleen Collins, a City College film professor and playwright at the time she filmed Losing Ground, was born in 1942. A French major at Skidmore, she was elected class president and spent time in the Republic of Congo on a service trip. Her pre-filmmaking life included several trips to the South in the early ’60s as a field worker, canvassing for black voter registration; a John Hay Whitney scholarship, which took her to the Sorbonne, where she first took a film course; a period working for WNET, where she trained as an editor; and finally the professorship, all the while continuing to write stories independently. All of these professional activities took place against a backdrop of marriage, two children and then divorce.

A CUNY student encouraged her to try film directing, and her first attempt, The Cruz Brothers and Miss Malloy (1980), was made with an initial investment of just $5,000, raised from friends. Filmed around the Nyack and Piermont areas where the family lived, it was praised but never released commercially or shown widely.

In 1982, despite the obvious dearth of distribution mechanisms for low-budget feature films directed by African-American women, and despite a cancer diagnosis (unrevealed to her family), Collins followed up with her second feature. This time, she wrote an original screenplay, very much taken, said Lorez Collins, from her mother’s own life, despite some alterations.

Lorez Collins described Losing Ground’s story as concerning “a philosophy professor, very much in her own head. She’s married to an artist, her mother was also an artist, and she feels discounted because she is not an artist. It’s very much a story of this couple, during the summer. It’s funny and intellectual and kind of sexy, and very much feminist with both a black perspective and a feminist one.”

Interestingly, Lorez Collins feels that because the story itself does not overtly examine “being black, it made it harder to sell,” back then. “It’s really a story about a woman’s interior life. The race stuff is superficial; there are some allusions to it, but so much more about this woman and her own struggle.” Aside from showings at film festivals, and one airing on WNET, the film languished, its rare portrayal of black professionals largely unseen. It disappeared, with just one 16mm print preserved at Indiana University’s Black Film Archive. Collins died from breast cancer in 1988, leaving behind Nina and her brother.

Cut to about four years ago. By then Lorez Collins herself had married, had children and divorced, passages that led her back to her mother’s written work; for years she had left things untouched because her mother’s death was such a painful experience. Then letters started arriving from DuArt Film Laboratories, repository of thousands of film reels mentioning storage fees. Lorez Collins initially ignored them. Eventually, she understood that these were probably the only copies of her mother’s films.

A talk with Professor Terry Francis, then a Yale University professor (now Indiana University) who includes Losing Ground in her course, convinced Lorez Collins of the importance of preserving these works through remastering, despite the costs. From Francis she learned that for black female film students “have never seen a representation of this, and it blows them away. My mother was definitely doing something that really wasn’t done and still isn’t done.”

Once in possession of the newly remastered films, Lorez Collins approached film distributors. After a few passes, she met with Milestone Films, which she described as having a “great reputation as an independent discoverer of lost films.” They signed a contract and “I hosted a screening in TriBeca for about 100 friends, it went really well, I was happy with all of it, and checked in with Milestone about once a year. Then, three months ago, a call came from the Film Society of Lincoln Center. They were doing a film series, [Tell It Like It Is: Black Independents in New York, 1969–1986] at the Walter Reade Theater, and they wanted Losing Ground to be the centerpiece. Why they chose it, I don’t know, except that it’s a very warm, funny, cool movie.”

She added that “10 days before it opened, The New Yorker reviewed it, saying that ‘had it been shown in its time, it would have changed film history.’” What she calls “great write-ups on indie film blogs” came next, followed by “The Village Voice and then a huge, front-page Arts section story in The New York Times. At opening night I found myself having to speak to people I knew as a child — many familiar names, a fun event. Since then it’s continued to be like Cinderella … It’s all completely surreal.”

She added that “10 days before it opened, The New Yorker reviewed it, saying that ‘had it been shown in its time, it would have changed film history.’” What she calls “great write-ups on indie film blogs” came next, followed by “The Village Voice and then a huge, front-page Arts section story in The New York Times. At opening night I found myself having to speak to people I knew as a child — many familiar names, a fun event. Since then it’s continued to be like Cinderella … It’s all completely surreal.”

Lorez Collins, who has lived in Philipstown part-time for years, wanted her friends here to be able to see it. Thus, the Downing Film Center, at 19 Front St. in Newburgh, will show it on Sunday, March 22, at 1 p.m., [rescheduled from March 15] with Lorez Collins and the film’s music composer, Michael Minard, in attendance for a Q-and-A. Tickets are $10. The film will be shown again on Monday, March 23, at 7:15 p.m. at the regular price. Tickets can be purchased in advance on Downing’s website or call 845-561-3686.

Images courtesy of Milestone Films