A conversation with Evan Pritchard, a descendant of the Mi’kmaq

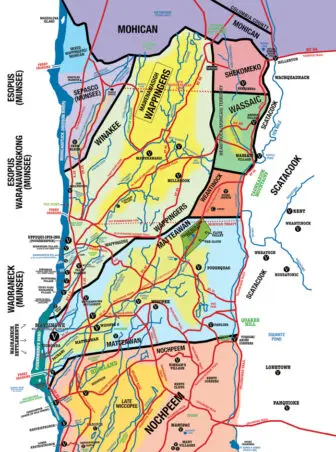

Evan Pritchard, a former professor of Native American studies at Marist and Vassar colleges and founder of the Center for Algonquin Culture, is the author, most recently, of Mapping Native New York. He spoke with reporter Michael Turton.

According to the 2020 census, more than 5,500 people in Putnam, Dutchess and Orange counties identify as Native American. Does that surprise you?

I’m very surprised, because a lot of Native Americans don’t have a lot of respect for the census and government meddling. So, they might not — and I don’t generally — indicate that on the census.

What was the Native American population of the Hudson Valley at its peak?

Nobody agrees on that. It was probably about 5,000 per borough in present-day New York City and 10,000 per county in the Hudson Valley, which had some of the best territory for growing, fishing and hunting. But nobody really knows.

How would you describe the Wappinger and other Algonquins who lived in the Hudson Highlands?

They were hunters, and a lot were fishermen. They knew their rivers inside out and upside down; they mostly named their villages after them. They grew corn, especially where the tide would rise and water the plants. Women often had dominant roles, but it was not a matriarchal society. The women were tough but often they weren’t equal because the men were stronger, taller and more muscular. Some men weren’t always nice to the women, but that was individual; it was not their philosophy. They were surrounded by friends, allies and relatives, so there was little warfare, although they were capable warriors. Using bows and arrows, they held their own against guns.

Is it true there was a ferry system for crossing the Hudson?

Yes, they had ferry routes all along the river. In Poughkeepsie, it was at the bottom of a trail that is now Main Street. Someone would stand by the river, hold a large pole with a white cloth attached and wave. The ferry operator might be a young guy who wanted some extra wampum. He would land his canoe, put out his hand and they’d give him beads, furs or whatever, and he would take them across. It was the same at Beacon, Newburgh, near Bannerman’s Island, at West Point and other locations.

What were some of the significant trails in the Highlands?

The Mohican Trail was likely the most important. It started in what is now Manhattan and went quite far north to Mohican territory. Later it became Old Albany Post Road, and then Route 9. The original trail was probably created by huge mastodons that followed the ridge. They saved Native Americans a lot of work! It was a trade route because there were many items along it that could be collected. What is now Route 52 through Fishkill and Beacon was once a trail that continued west from Newburgh to the Delaware River. Route 9D was also an important trail. Many served as portages, connecting one river to another.

What present-day places were significant to the Wappinger?

Dennings Point in Beacon was one. Many tribes gathered there — it was crowded, because that’s where trading was conducted. It was serious stuff; landings like that held society together. Cold Spring was a decent-sized village, and it had several satellite “fires,” or villages, around it. I can’t say authoritatively that Little Stony Point was significant, but I’ve spent a lot of time walking around there and it is a magical place, a place of power. Maybe it was a crossing. There is also archaeological evidence, including copper tools, of a fire near the present-day Garrison train station.

Is it true Native Americans have no word for “time”?

When I went up north to the bush to learn the Algonquin language from Micmac elders, I asked what the word for time was. My teacher said, “We don’t believe in that.” They may use the word when, such as “when the sun is there” or “when oak leaves are the size of a mouse’s ear,” but there’s no word for the concept of time. It’s very much in harmony with what Einstein thought in terms of relativity.

Today, do Native Americans in the Hudson Valley gather as a group?

We hold powwows for ourselves, and to educate others. More than 20 years ago, Gil Tarbox said Daniel Ninham (1726-1776), the last sachem of the Wappinger, came to him in a dream and said, “Nobody remembers my name anymore; do something to help them remember.” That led to the Daniel Ninham powwow, and for years they boomed. They’re the backbone of our community; thousands came. I went to 19 of them. But a couple of years ago, almost all the powwows collapsed; the organizers got older and wanted to retire. COVID-19 killed what was left of the powwows. They are just now starting to come back.

What is the goal of the Center for Algonquin Culture?

Part of our mission is to protect, preserve and restore the dignity and culture of every Algonquin nation, large or small, and to unify the Algonquin people. We’re spread all over Canada, the U.S. and Mexico. That’s a tough job. We also want to educate the public about Algonquin culture and history and its central role in the development of modern-day America.

How well are schools educating students about Native Americans?

Since moving here in 1982, I’ve been trying to help schools teach Native culture in a respectful way. It’s been discouraging, overall, but during COVID, and since the George Floyd killing started to be resolved, my phone has been ringing a lot. In the last year, it’s been a sea change. Private schools have been working hard. Public schools lag behind, but they’re certainly better since COVID.