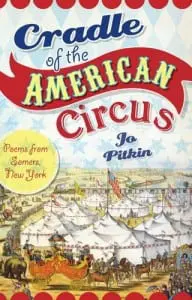

Author to read from new book at Butterfield Sept. 23

By Alison Rooney

Although it is but a stone’s throw away, geographically speaking, few in Philipstown are likely to know much about the almost outlandish history of the northern Westchester town of Somers. Philipstown poet Jo Pitkin didn’t know much more than the broad strokes despite having grown up there.

She knew, as she says in the prologue to her new book, Cradle of the American Circus, that “an elephant loomed large in Somers history. My childhood was threaded with tales about Old Bet, the town’s resident pachyderm. … At school I cheered for the Tuskers … an elephant was emblazoned on our shiny fire trucks.”

That much alone is fodder enough to pique the imagination, but what Pitkin discovered, after deciding to write a sequence of poems about her hometown’s unusual history, was that the 19th-century farmers and drovers of Somers were the progenitors of the traveling menagerie business in this country, importing and displaying large animals from Africa and other far-off precincts of the globe for the first time.

Making use of Somers’ proximity to the ports of New York City, they used the coach roads and the large swathes of farmlands to their advantage and coupled this with their expertise in handling farm animals to create a fantastical and lucrative new enterprise.

Working over an extensive period of time, Pitkin wound up “pulling a thread and going in another direction. … I let the material lead me.” Initially, old-fashioned investigation and research began through Pitkin’s local library system (at that time she was living in Massachusetts). In that pre-Internet universe, her thirst for more details led her back to her hometown, to the Somers Historical Society archives stored at the aptly named Elephant Hotel. “I opened old metal filing cabinets crammed with fascinating material: hotel receipts, bills of sale, letters home, passports. It appeared that no one had looked in these files for a long, long time.”

Stimulated by what she found, she further immersed herself in literature relating to small-town American life, letting it shape the way she would tell her story, eventually settling on a mix of poems and prose, the prose giving a context to the poems, as well as giving her a foundation for the imaginative leap she would then give to interpreting this slice of history and its players.

The prose portions of the book began as notes that Pitkin originally envisioned forming a lengthy set of footnotes to the poems. As the notes kept increasing, Pitkin decided to move them forward and to incorporate them into the book itself. Illustrations were added at the suggestion of the publisher to complete the now three-pronged approach.

Humans have been fascinated by displays of exotic animals as far back as ancient Rome, where the beasts were paraded around arenas. The details on the arrival of the first elephant in this country are slightly murky, but it is an either/or that one was brought from India in 1796 by a sea captain, or that the first import came from Africa, via London, purchased at an auction in the early 1800s by the brother of Somers’ Hachaliah Bailey and shipped across the Atlantic, then up the Hudson, where it was unloaded at Ossining and walked to Somers.

Humans have been fascinated by displays of exotic animals as far back as ancient Rome, where the beasts were paraded around arenas. The details on the arrival of the first elephant in this country are slightly murky, but it is an either/or that one was brought from India in 1796 by a sea captain, or that the first import came from Africa, via London, purchased at an auction in the early 1800s by the brother of Somers’ Hachaliah Bailey and shipped across the Atlantic, then up the Hudson, where it was unloaded at Ossining and walked to Somers.

Conjecture about the reasons for the purchase included the ability of the elephant to help in clearing farmland, and, more simply, that the intention was always to display the animal.

Whatever the beginnings, the first few decades of the 1800s saw the rapid rise in popularity of traveling menageries — differentiated from the raffish circuses, which were considered a bit shady and controversial, with their acrobats, clowns and scantily-clad women.

The menageries, traveling separately, had no such connotations and were perceived as scientific. Initially, says Pitkin, the animals were just displayed and didn’t perform any tricks, but as things evolved, the showmanship aspect came more into play, and eventually, by the mid-19th century, the menageries and circuses were joined.

It was the community of farmers and drovers of Somers, led originally by Bailey, that transformed the menagerie business. Many were astute businessmen, and seeing the curiosity engendered by glimpses of these creatures, they realized there was a large touring market. At one point, Pitkin says, 130 men, largely from northern Westchester and eastern Putnam, formed a consortium and basically held a monopoly on the business. It was the showmen’s entrepreneurial earnings that essentially built Somers.

As time went on, and audiences grew bored with the same old animals, new ones were imported and shown. Pitkin says that it is important to remember that in this pre-photography era, people had no preconceived realistic idea of what these animals looked like, relying on the written word and posters of the day, which often depicted the scale incorrectly, with tiny humans dwarfed by gigantic lions and the like. Thus, fascination ran high.

With all of this as a jumping off point, Pitkin grew curious, and her questions, which fed her poems, drove her further in research. Frustrated by how little she could find, in particular relating to how people felt about it all, she mused on many perplexing things: How were these animals shipped, and how were the cages constructed? How did they maintain their diets in this wildly different climate? With tales of dangerous animals stored in barns, and even a rhinoceros kept in a creek near a home, how did the wives and families of the showmen feel about all this — were they fearful? Did they form their own relationships with the animals?

This fertile ground gave rise to a variety of perspectives for the poems — one is written from the animal’s point on view, another takes the form of an inventory list, while many project the thoughts of the showmen. Rather than seeking to write a comprehensive history in poetic form, Pitkin simply wrote about what she connected to most, spurred on by, in some cases, firsts associated with Somers: they were the first to import giraffes, to design portable circus tents … the list goes on.

Pitkin writes “pretty much everyday.” Always interested in writing, she turned towards poetry in high school and eventually earned an MFA in poetry from the Writers’ Workshop at the University of Iowa. A long career in publishing has supported her creative life as a poet.

After working as an editor at Houghton Mifflin for years, she now works freelance from home, largely on textbooks, with clients all over the country. Pitkin’s “day job” writing is factual, with stipulations for number of lines and exact specifications. Writing poetry, on the other hand, relaxes her, as “it’s two different parts of the brain,” she says. With no deadlines and with the end product less scrutinized by a hierarchy of editors, there is inherent freedom.

In the mid-1990s, after living elsewhere, Pitkin decided to return to live near where she grew up. Remembering Cold Spring from visits when she was a teenager, she “looked around and ended up here.” She has been involved in many things literary and local, starting up a series of readings at Butterfield in 2002, bringing writers from both sides of the county together, and eventually bringing nationally known writers in as well. (For years she ran a similar group in Massachusetts.)

Her previous published work includes The Measure, and her individual poems have garnered awards and have been included in many anthologies, including Riverine: An Anthology of Hudson Valley Writers. Another new work, Commonplace Invasions, is to be published next spring by Ireland’s Salmon Poetry.

Pitkin will read from Cradle of the American Circus this Sunday, Sept. 23 at 3 p.m. at Butterfield Library. Copies of the book will be available for signing, and the program is free of charge.