Garrison native creates art to remember

By Alison Rooney

Nils Kulleseid makes his living with two tools: a chisel, and a mallet.

Raised in Garrison and based in New Paltz, Kulleseid is a stone carver. Most of his commissions are for gravestones and memorials.

Not surprisingly, he did not dream of becoming a stone carver while attending the Garrison School and James O’Neill High School, although he did love art and majored in art history at Hamilton College. After several years working for the U.S. Forest Service in Washington state, he returned to New York and became intrigued by the apprentice program in stone carving at Manhattan’s Cathedral of St. John the Divine.

He wasn’t accepted but was told that most master carvers came from England. So he embarked on a two-year vocational course in Weymouth, located near a limestone quarry that has been active for centuries. (Its stone was used by Christopher Wren in the construction of St. Paul’s Cathedral.)

“I have fond memories,” says Kulleseid, “although I was definitely not one of the better carvers. I wasn’t the quickest; I was cautious. We were learning how to make templates, in which we’d take a block of stone and make replacement pieces, like arches, which were very exacting as they had to fit perfectly into existing places in a church.”

Kulleseid, 49, says he preferred letter cutting, perhaps, he says with a laugh, because “the building’s not going to fall down if I don’t get the ‘M’ quite right.”

After finishing at Weymouth in 1993, he ended up in a Cambridge workshop working on “lots of pulpits,” he says. After a sojourn in Egypt doing relief carving for an English government visitor’s center, he heard of an opening in Cambridge at the David Kindersley workshop, which was known for its quest for quality and beauty.

“Kindersley had died, and the workshop was in transition,” Kulleseid recalls. “His widow took a chance on me with a one-year apprenticeship in lettering. The first month I didn’t touch any stone; I just drew an alphabet and she’d critique it.” Initially he worked mostly on memorials ordered by Cambridge University. “She’d do most of the drawing, then we’d come, rough it out, and she cleaned it up. As we got better, we got more real jobs.”

It was in Cambridge that Kulleseid met Susie Fenton, who would become his wife. With his work visa about to expire, the couple moved to the U.S. “I love England, its history, landscapes and especially its stone buildings,” Kulleseid says. “The American stone experience is not as prevalent.” He set up shop in New Paltz after his wife enrolled in nursing school at Ulster County Community College.

Then and now, most of his work comes through referrals, with his parents, Lars and Marit, spreading the word in Garrison and the Highlands. (See kulleseidstonecarving.org.)

Carver vs. Sculptor

“A sculptor assigns shape to an idea. A carver imposes a shape on stone, and must be able to do so reliably and in a manner that can be duplicated.” ~ The Stone Carvers Guild (stonecarversguild.org)

Kulleseid also made a valuable early connection with Dean Anderson, of Super Square Ironworks in Newburgh, who rented Kulleseid part of his studio and connected him with a commission to carve benefactor plaques at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

“That’s been huge,” he says. “I set up behind some screens to hide me from the public, but sometimes museum-goers peek in and are surprised to see me doing it all by hand, with no machine and not much dust.”

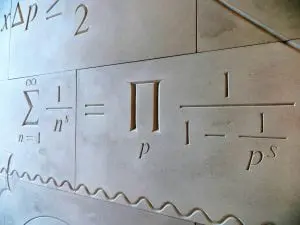

Closer to home, examples of his work can be seen on a slate bench on the Boscobel Woodland Trail or on a wall inside the geometry and physics building at SUNY Stony Brook that he filled with numbers and mathematical formulas.

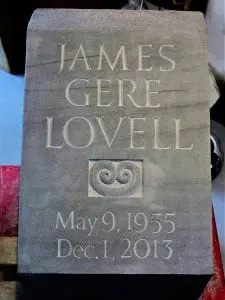

But some of his most affecting work is on display at cemeteries. Because his studio is near Woodstock, he was commissioned to carve a memorial stone for musician Levon Helm. And in the churchyard of St. Philip’s in Garrison, a stone done at the same time commemorates Jim Lovell, who was killed on Dec. 1, 2013, in a Metro-North train derailment.

Nancy Montgomery, his widow, commissioned Kulleseid to carve a gravestone for Lovell, which was placed this past May at his gravesite. But she had a challenge for the artist — she wanted him to carve a symbol known as a double koru, on the stone. Her husband had worn one around his neck for as long as she could remember.

“He got it on a trip to New Zealand,” Montgomery says. “It represents new life and family. He called it a taonga, which is the Maori word that means spiritual treasure. A double koru becomes a taonga when it takes on the spirit of those who wear it.”