Roger Panetta is a professor of history at Fordham University and a co-author of The Hudson: An Illustrated Guide to the Living River, which on Jan. 15 was released in its third edition. Hudson River Sloop Clearwater is hosting an online lecture series on the book that continues on Jan. 27 and Feb. 3. See clearwater.org.

What’s new in the third edition?

There’s been a lot of new historical interpretation. We look at the river now — or at least I do — less as a conflictual place, where we have good guys versus bad guys. There’s a much more nuanced sense about what the art of the Hudson River School means, about how the art is used as a tool, how our history of that has changed. Because that’s the business of history, the revisions. It’s the lifeblood of history, and the same is true of the river.

For example, if I’d had time, I would have written more about William Wade’s 1847 panorama of the Hudson River, because I know more and my perspective has changed. But as Steve [Stanne, another co-author] says, that’s not the intention. He keeps us focused by saying, “Our view is shallow, but wide.” What we hope is that it invites people to look deeper.

Why was that 1847 panorama so important?

As the U.S. expanded, people wondered: In what way can I represent that vastness? There were panorama buildings in New York City. You climbed up the stairs, you stood in the middle of a platform and you looked around at the [painted] panorama. The idea was to make you think it was real, to fool your eye. People paid admission; it was a principal form of entertainment.

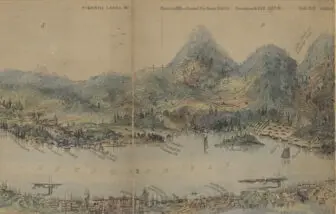

The 1847 panorama was a folded map, about 4 by 6 inches, that you could buy when you boarded a steamboat in Manhattan. It scrolled out to about 7 feet. As you went up the Hudson, you could use the panorama map to follow the river. It was based on a sketch of the river, both sides from the middle. Like the panoramas in buildings, his key was the horizon. He was helping America learn about America, which was very important, because you had immigrants coming into the country and they wanted everyone to have the same baseline of knowledge.

In the second edition, you wrote about how after the War of 1812, America turned to the landscape as something to unite the country. We are again at a tumultuous time. Does the landscape have the potential to unite us?

Yes. It has a long history of doing that. For example, during the Depression, there was an explosion of books on the American landscape, about nature, including several about the Hudson River. The idea was: “Come to nature and you come to our origins. You touch the foundations. If you want to get over the anxieties of the Depression, take a trip to the Adirondacks.” That was the goal of all the “see America” books: See who we are not by reading the history but by going back into nature, visibly feeling America.

On the 1847 map, Mount Beacon is referred to as Grand Sachem. Do you know why?

I don’t. But if you look at the river, and river towns, and at the number of names associated with native populations, I’m always startled by the failure of the public, and myself, to connect those to native peoples. In the 1847 map, there’s never much of a connection besides that name, even though he’ll write: “This is where that battle in the American Revolution was.” And he’ll sketch it in, even though there may not be any sign of that in the landscape. So when he wants, he adds, and when he can’t see, he forgets. I think there’s a great forgetting. Where is the reckoning here? And it’s going to come with the hidden history of the Hudson. Where is that? Where are the Black communities and native legacies?

What will that historical reckoning look like?

I don’t know, but I know it’s going to happen. As a historian, I can feel my brain has been tweaked in the past five years to ask questions that I didn’t ask before, to be more sensitive to those things. And to assume I’m missing something. One of the things I love about the panorama is that you can study it and study it and always see new things. You never come to a set position, because it keeps revealing itself. If I look at it now I see different things than I saw five years ago. And I’ve been playing with the thing for 20 years.