Using Nazi records, a journalist tracks his father’s life

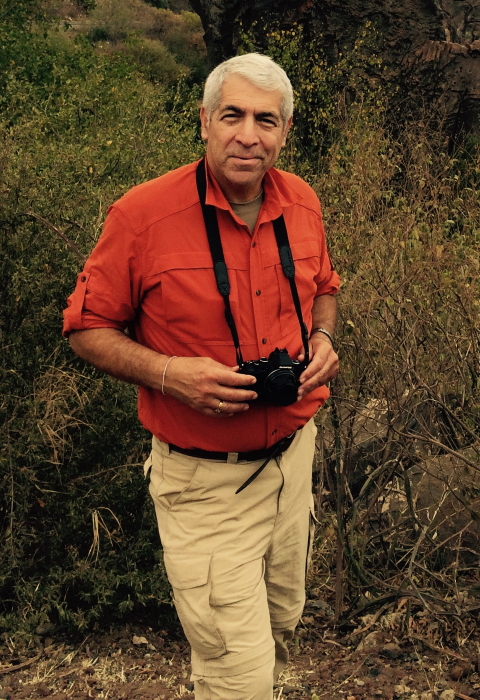

As a foreign correspondent and news desk editor working out of London and later Jerusalem, Mel Laytner was well-schooled in the necessity of fact-checking.

Reporting for United Press International, a news agency, Laytner was adept at shaping complex issues into just-the-facts stories and presumed he would apply these methods to any future writing.

But when he began researching what he describes as an “investigative memoir” based upon his mild-mannered and introspective father’s experiences as a black-market ringleader and survivor of Auschwitz and other Nazi concentration camps, as well as his life as a refugee, the writing wasn’t as straightforward as envisioned.

“I fought and objected to the notion that people suggested I would have to examine my relationship with my father in a personal way,” says Laytner, who is a board member of Highlands Current Inc., which publishes this newspaper. “It took a while for me to accept the fact that I was not just reporting on amazing documents” he had discovered.

Those documents proved essential to the story, because his father only shared vignettes of his traumatic experiences, and “he scrubbed the stories of any blood. With benefit of 20/20 hindsight — and you have to be cautious of your own memories — there were clearly things he didn’t talk about.”

It was left to Laytner to apply his professional skills to a personal story that resonates beyond his family.

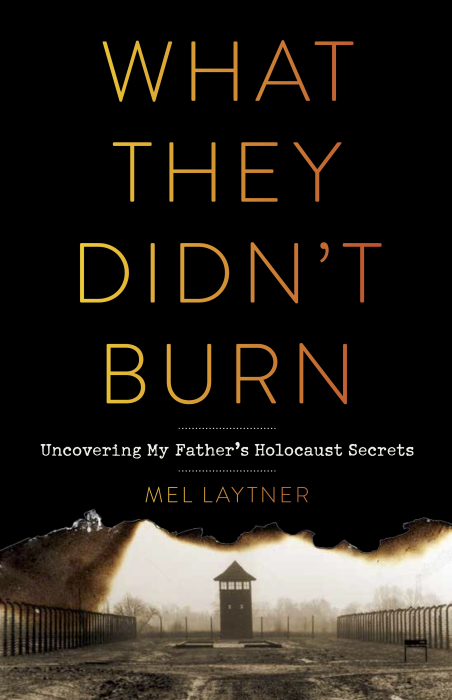

His book, What They Didn’t Burn: Uncovering My Father’s Holocaust Secrets, which was published on Sept. 20, uses the Nazi paper trail to shine a new light on his father’s life and on the collective experiences of prisoners at the camps.

To do this, Laytner, who lives in Nelsonville, had to become a determined detective, frequently in chase of elderly sources with potentially unreliable memories. He also had to question his own memories.

“When I was 10, I asked my dad, ‘Why didn’t you escape?’” he recalls. “He told me about an elaborate scheme, which didn’t make sense to a child. Then, this German document comes my way which confirmed the story. I thought: ‘What about all these amazing survivor stories?’ If I can show the truth by corroborating one man’s journey through the war, it shows that these things did happen, in an independent way.

“In discovering an important document, I felt that a curtain, a divider had been lifted,” he said. “For a long time for me it was a story; I was a journalist and it was a story. As I got into it deeper I decided that I would not report stories that I couldn’t corroborate without cross-checking with documents or other witnesses. Throughout the book I used the reporter’s rule of a minimum of two sources” for each assertion. “The only things that I don’t have a second source for are my own memories,” he says.

Laytner, who studied political science at the City College of New York and journalism and international and public affairs at Columbia University, says “the temptation to cross from history to historical fiction is enormous, and there were scenes I created based on fact but in which I initially filled in the blanks. But if you cross over into fiction, you lose the authenticity of the memoirs.

“The hardest part was the personal memoir; the easy part was doing research and writing up the research,” he says. “The hard part went against everything I was trained to do, forever.”

Although one document sparked his investigation, Laytner didn’t think he had a book until three others came his way. Even then, he wasn’t sure how to put the research in the best perspective.

“It wasn’t until two or three years into the process that I began to reconcile that it had to be a memoir,” he says. “I realized that you make a better story if it involves people. I wanted to take the readers along on my journey of discovery, including my frustrations of running into brick walls.”

The extended research paid off. “I’d be looking for evidence of one thing and I’d discover something else,” he says. “I’d learn of something in Year One and in Year Five it would come back and be key.”

He decided to use two voices: third person past tense for historic accounts, and first person for the descriptions of his research. “I wanted it to be credible so my former colleagues would look at it and think, ‘He did a good job reporting, and he maintained his street cred.’ But I also entertained hopes that it would appeal to an audience greater than people affected by the Holocaust.”

He initially organized the book chronologically but finally followed his path of discovery. Eventually, the two paths meet and “the 23 documents that I found [relating to his father’s experiences] show the evolution of Nazi policy from ethnic cleansing to genocide, as well as my father’s attempts at coping with what was going on.

“When I was growing up I sort of discounted what it took, on a nitty-gritty action level, to survive the camps,” he says. “I had an appreciation, but I didn’t get what it meant to go through this day after day and make micro-decisions constantly in order to have a better chance of living another day. By the time I finished, I understood that this guy — my dad — did a lot of stuff to improve his luck.”

On Oct. 5, the Museum of Jewish Heritage will host a virtual discussion with Laytner about What They Didn’t Burn. Register at bit.ly/laytner-talk.