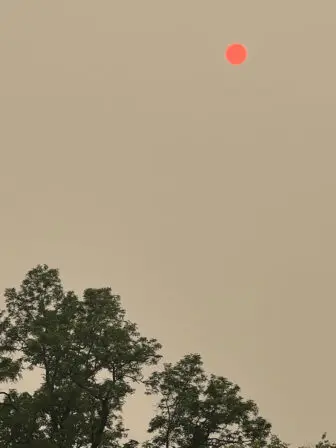

Iwoke up a week ago Wednesday and was confused as to why there was an intense orange sunbeam across the floor.

“How long have I been asleep?” I wondered. “And why is the sun setting in the east?”

My disorientation was the least-harmful effect of the three-day smokeout. Researchers at Stanford University calculated that June 7 was the worst day for wildfire smoke pollution in U.S. history. The day before, June 6, was the fourth worst. (Nos. 2 and 3 were caused by California wildfires over two days in September 2020.)

Outdoor air pollution contributes to the deaths of 4.2 million people annually, according to the World Health Organization, and wildfire smoke is one of the most toxic pollutants out there, partially because as forests burn, they often spread to houses and everything inside. Imagine huffing every cleaning product under your sink. Imagine doing it for every sink in town, plus everyone’s melting microwaves.

As I write this, the Highlands sky is again blue and the air quality map has returned to green, so it’s understandable if people are relegating the haze to another of those weird incidents, such as a worldwide pandemic or fish falling from the sky. But in many other parts of the country, wildfire smoke is more common, although still unexpected.

“I was talking to a colleague in Seattle, where they get smoke all the time,” Winslow Hansen, a fire and forest specialist with the Cary Institute in Millbrook, told me when I called to ask him about our orange-out. “He said: ‘Every summer, we’re surprised by the smoke, too.’ It’s something about the annual cycle where you can easily forget about it.”

A forest ecologist, Hansen directs the newly created Western Fire and Forest Resilience Collaborative, a multi-year project that’s using fieldwork, remote sensors and simulation modeling to provide the best science possible to decision-makers “grappling with how to manage a fire regime that is increasing rapidly with climate change and increasing fuel loads.” In addition, he said, it will provide guidance on “how to manage the forest so that we can live sustainably with fire rather than in in opposition to fire.”

Because Hansen’s work is focused on the west, he said he was just as surprised as everyone else by the amount of smoke pouring down from Canada into New York state and the Hudson Valley. The boreal (cold weather) forests of eastern Canada generally aren’t as vulnerable to massive, prolonged fires as the temperate (seasonal) forests of the west are — not because they can’t burn, but because they’ve been allowed to burn.

“The reason California fires are so challenging is that we’ve been suppressing fire for a century, which has led to a buildup of fuels,” Hansen explained. Fire is an important part of the forest ecosystem. Some trees, like the pitch pine, need fire to reproduce. Indigenous cultures have long known the importance of setting fires intentionally in certain times and places to prevent woody understory from becoming denser and becoming fuel for more dangerous, out-of-control fires anytime lightning strikes.

Since the 1930s, U.S. policy has been to put out any fire by 10 a.m. the next day, which doesn’t give fires the chance to clear out understory. Add in the hotter and drier summers that climate change has been bringing and you have an explosive combination.

The Canadian wildfires haven’t been as big in the past because the fires were allowed to burn and the boreal understory isn’t as dense. But once again, if the climate is hot and dry enough, anything will burn.

This could spell changes for the Catskills and Adirondacks, which haven’t been prone to California-style wildfires because the understory is comprised of species that retain moisture well and are less likely to burn. If the warming climate dries that understory out, coupled with more summers of drought like we had in 2022, it could lead to wildfires the likes of which New York hasn’t seen.

Forest management policies are slowly changing, and Hansen said he is glad to see intentionally set, low-severity fires and mechanical thinnings of forests are being implemented more frequently and more thoughtfully.

“That’s one of the most inspiring strands of this story,” he said. “There has been an embracing of cultural burning in a way I couldn’t possibly have anticipated. People are being empowered to reinvigorate cultural practices of burning that were largely exterminated in the 20th century.”

But setting a prescribed burn is expensive: It takes a lot of people to treat the sections you want to burn while protecting the sections you don’t want to burn. It gets even more complicated if you’re setting a burn near houses — not to mention stressful for the people who live in the houses. This is where Hansen’s work out west may prove vitally necessary if our local forests get hotter and drier. The 2019 Sugarloaf and 2020 Breakneck fires in the Highlands were relatively small. But with our population density, it doesn’t take a widespread fire to put people at risk.

“We need to understand what our fire risk is, and how we can take proactive strategies to mitigate that risk,” Hansen said. “We’ve been largely isolated from this fire crisis that’s been unfolding around us, and we may not be in the future.”