Beacon schools launch pre-K special education program

Shawna Ryan’s son is one of the children the Beacon City School District was hoping to reach.

The Beacon resident said she and her husband noticed that their son was having difficulty regulating his emotions and had “atypical” tantrums caused by stressors that “didn’t align with what you would expect to upset a 3- or 4-year-old.”

Early last year, the parents had their son evaluated by the school district, which admitted him to its pre-K program beginning in September. After a long wait, a pediatric neurologist diagnosed him as autistic a month later, on his fourth birthday.

Ryan didn’t know it, but Heather Chadwell Dennis, the assistant superintendent of pupil personnel services, had been working for a year to launch a state-approved preschool special-education program.

The district already had plans to expand its full-day pre-K program to each of its four elementary schools (voters in May 2023 approved funding). But after joining the district in June 2022, Chadwell Dennis said she realized that Beacon needed to get creative to reach the youngest children with learning difficulties.

Many public school districts in Dutchess County offer pre-K classes, and some of those are “integrated,” with children receiving general education and others with special needs in the same classroom. Typically they are taught by a teacher certified in general education with help from private therapists hired to visit the classroom.

Beacon stands out because it has a teacher, Tara English, who is certified in both general and special education. She has 11 pre-K students in her class at Sargent Elementary, including five with learning disabilities.

When discussing the program, Chadwell Dennis said she didn’t have a model to follow while going through the arduous process of getting state certification. (Other than the school district, there are two private preschools in Beacon that are state-certified for special education.)

First she had to submit an 18-page document to argue there was a need in Beacon. A 59-page application followed. In addition, she had to provide floor plans for Sargent, safety access routes, bathroom measurements and the district’s electrical bills, to name a few of the requirements.

“It was complicated because it’s not a language I normally speak,” Chadwell Dennis said. Half a dozen staff members from the state Education Department met with her on Zoom calls for months to help prepare the application. The approval letter arrived Aug. 25, a week before school began.

There are more pre-K children with learning disabilities in Beacon than the five in English’s class, but Chadwell Dennis said creating it was an important first step. “To a family of a 4-year-old experiencing learning difficulties, this class is like a gift,” said Superintendent Matt Landahl.

‘Like a classroom family’

On a sunny but cold Tuesday morning in December, English led the class through its morning meeting.

The students, who are all 4 years old, briefly discussed the weather before beginning warmup exercises. Following the teacher’s lead, the children played head-shoulders-knees-and-toes and then transitioned to jumping jacks.

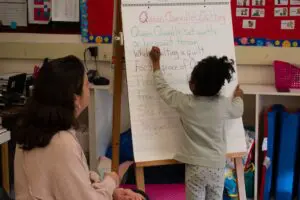

From there, they worked on the alphabet. English read a poem filled with “Q words” and the students took turns circling uppercase and lowercase Qs on a flip chart.

exercise. (Photo by Una Hoppe)

English admits she was nervous when Chadwell Dennis and Sargent Principal Cathryn Biordi approached her last spring about leading the class. The idea for an integrated classroom is to keep the children with learning disabilities from feeling isolated while exposing general-education children to classmates with diverse needs.

Together, the children are learning basic concepts, such as sounds, letters and to color within the lines, as well as how to clean up after themselves and treat others with respect, “almost like a classroom family,” English said.

Speech therapists visit three times every week, and occupational therapists twice weekly, to supplement English’s instruction and work privately with students who have individualized education program (IEP) plans tailored for their disabilities.

Other than the therapists’ visits, “it doesn’t appear like there’s anything different happening,” said Biordi. “But what people don’t see is the expertise in differentiating instruction.”

English and Jeanine Cruz, her teacher’s aide, also work with the children on sharing and communication skills. For example, if two children want to play with the same toy, they’ll use an hourglass to remember when it’s time to share with the classmate. Coping skills and self-regulation will be necessary next year in kindergarten, when the students will expand on the letters, rhyming and counting they’ve learned.

“If we can teach them to recognize how they’re feeling, to communicate with their peers and be kind human beings, those are the things they’re going to need throughout school,” English said. “The letters and sounds — that will all come.”

She noted that she knew the class was working when she heard one child politely ask another if they could take turns with a puzzle. “They’re trying, and that makes me happy to see that they are using the tools that you’re teaching them,” she said.

Ryan said her son has found the “niched space” he needed. “They’ve created a safe space for him to work through his challenges without as much of a risk of something going wrong,” she said.

She was quick to clarify that it hasn’t been “all roses and peaches” in the classroom. If her son drops a toy on the ground, for example, and a classmate picks it up for him, he is still prone to perceive that as the classmate taking the toy away from him, which could lead to an outburst.

But because of the small class size, English or Cruz can note what’s happening, watch her son for cues and report back to her. “That way I can more effectively beat the same drum” regarding emotional regulation and coping when he’s at home, she said.

Ryan’s long-term goal is for her son to help choose his educational path — whether that’s in a school for special-needs students or in an integrated setting. But before that can happen, she needs to see that he can consistently apply the healthy protocols he’s learning at Sargent.

“I want him to have a choice, but I can’t give him that until I see that he’s in a good place to make a choice,” she said. “Without a doubt, I’m seeing improvement on a day-to-day frequency. I’m noticing better communication skills and better awareness” of social cues and triggers.

A daunting task

Since starting the program, Chadwell Dennis has had administrators from many other districts call for advice on wading through the state’s application process. “When they see how big it is — the application itself is a barrier to these programs,” she said.

She still feels anxiety, as well. “It takes a lot of trust and I don’t want to let anyone down,” she said. “I’m feeling a little bit like I’m in the hot seat. But I believe all children have the right to the most inclusive educational setting, and Beacon supports that at a very high level.”