Report details local impact of climate change

In 2018, The Current published a series called “How Hot? How Soon?” that asked how climate change would affect the Highlands.

Now, thanks to a newly released report by the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA), we have an answer: Annual average temperatures in Dutchess and Putnam counties are projected to increase between 4.1 and 6.1 degrees by the 2050s and between 5.7 and 10 degrees by the 2080s, compared with the averages between 1981 and 2010. The state’s average temperature has increased by 2.6 degrees over the last century.

The report says that, without “serious action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions” that cause global warming, New Yorkers can expect the decades to be significantly hotter, with many more extreme weather events.

“We have known for a long time that climate change is real,” said Radley Horton, a Philipstown resident who is a scientist at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory and worked on the report. “It’s going to be severely impactful, humans are responsible and there are solutions.

“You could have discerned that from a report written 30 years ago,” he said. “But now climate change is happening faster than we thought it would. We could be heading into a future that nobody thought was possible 10 or 20 years ago. And I suspect a portion of folks in the Hudson Valley are probably starting to feel that way too.”

After the severe flooding in July and a warm winter, “people can feel that this is outside of that range of natural variability,” said Horton, who will speak with David Gelber, head of The Years Project, who also lives in Philipstown, on April 6 at the Desmond-Fish Public Library about the current state of climate change.

The NYSERDA report, at nysclimateimpacts.org, is extensive but incomplete. A section that details the projected economic impacts of global warming on the state will be released later this year. Amanda Stevens, the report’s editor, said drafting the final chapter has been eye-opening.

“The amount of warming isn’t set in stone yet,” she said. “We shouldn’t [view it as] either reduce our emissions or adapt. We need to do both. That’s a key takeaway.”

The New York State Climate Impacts Assessment doesn’t address how the state could reduce greenhouse gas emissions because a 2022 scoping plan covered that. However, Stevens said that the assessment can help communities and decision-makers prepare.

“I use that term decision-makers broadly because it could mean municipal governments, state agencies or even farmers who need to understand what kinds of crops they’ll be planting,” she said.

Fleeting winters, brutal summers

The assessment divides the state into 12 regions and dives into how climate change will affect each one.

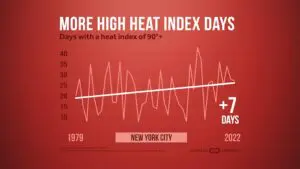

The projections for the South Hudson, which includes the Highlands, were calculated using long-term data collected at a station in Dobbs Ferry, Westchester County. The Highlands has an average of 18 days yearly when the temperature reaches 90 degrees. Based on the data, we can expect that average to jump to 41 to 64 days by mid-century and 48 to 87 days by 2100.

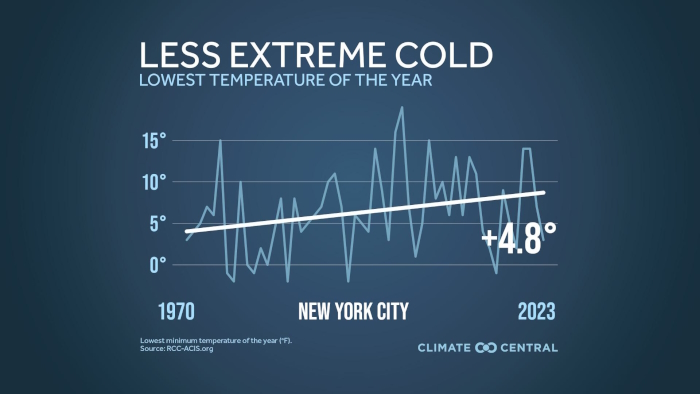

We can also expect milder winters, like the one that just passed. Historically, our area averages 105 days where the temperate dips below freezing. That number is expected to fall to 54 to 82 days by the 2050s and between 25 and 67 days by the 2080s.

Storms like the one that the Highlands experienced on March 23, when more than 2 inches of rain fell in 24 hours, are projected to become more common. Instead of the current average of three storms a year, the assessment projects 4 or 5 by mid-century and 4 to 6 by the end of the century.

Total annual precipitation is projected to increase between 4 and 11 percent by the 2050s and 7 and 17 percent by the 2080s. That increase in rain, combined with projected sea level rise that affects the Hudson River (12 to 17 inches by the 2050s and 25 to 46 inches by the 2100s), means our area can expect more flooding and storm surges, especially when hurricanes are added to the mix.

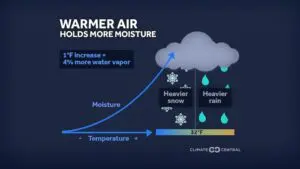

Droughts will become more common, the report says, a finding that may seem at odds with projections of wetter summers. But as temperatures increase, the atmosphere holds more moisture.

“At the same time, those high temperatures are evaporating more water from plants and the soil,” Stevens said. “So there’s more moisture going into the atmosphere, and the atmosphere can hold more of that moisture. When it rains, we get a lot of it coming down at once. In between, we’ll potentially get these periods of drought; because the atmosphere is holding more moisture, it doesn’t have to rain as often.”

Horton suggested that the extreme weather the Highlands has experienced is a good indication of what to expect. “What if it was more severe?” he asked. “What if it was a longer heat wave? What if the power was out for longer? What were those points that almost broke in our system, and what can I do to protect myself next time?

“Some of the things that we thought about during the pandemic, like having a supply of non-perishable food on hand, are useful from a resilience perspective.”

The nonlinear future

Besides geographic regions, the report details the challenges that global warming will pose to New York agriculture, transportation, buildings, health and safety and other sectors.

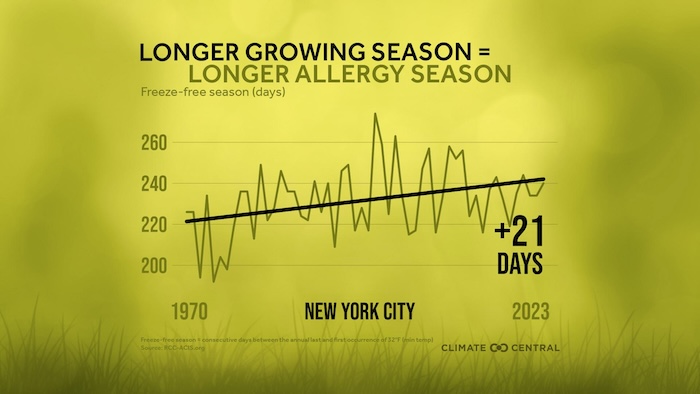

For farmers, the assessment warns that climate change will act as a threat multiplier. Extreme weather, droughts, heat waves, late spring freezes and more pests will exacerbate labor shortages and tight profit margins.

Farmers are well aware of these threats and are working to adapt by improving soil health, adding hoop houses and high tunnels to protect crops, installing wind machines and fabric orchard covers to counter frost damage and harvesting at night when the weather is cooler. But the assessment notes that farmers will need technical support, financial assistance and research.

In its chapter on buildings, the report recommends that new construction and retrofits consider building not for current conditions but for the climate to come. Green roofs are touted because they absorb water to mitigate flooding, counteract urban heat and keep buildings cooler, which decreases the need for air conditioning and puts less strain on the electric grid. The assessment urges builders to consider increased rainfalls, strategies for keeping out the increasing populations of rodents and insects that thrive in hotter and wetter climates and ventilation designed for outdoor air quality that is expected to worsen.

Many of the worst effects of global warming will be felt in communities the state has identified as “disadvantaged,” including Beacon. Many residents in such communities lack the money for retrofits to their homes or are renting.

That echoes a message repeated throughout the report: Climate change affects everyone in New York, but not everyone is affected equally. People of color, Indigenous peoples, low-income individuals, immigrants, the unhoused and older adults will be especially vulnerable, it says.

“Adaptation touches on all aspects of society,” said Horton. “Who’s vulnerable? Who can’t afford air conditioning? Who is exposed to terrible air quality that compounds with extreme events, such as heat waves, in ways that can lead to death or asthma cases?

“By addressing climate adaptation, we have a lens into a much broader campaign against various social ills, be they poverty, histories of redlining or failures to give everybody a seat at the table.”

Addressing these failures now is crucial because of what Horton refers to as “nonlinear trends” in climate data. Worldwide ocean temperatures, for example, have jumped in the past year for reasons that aren’t clear, even considering natural variability and seasonal variations such as El Niño, a climate pattern that pushes warm water in the Pacific Ocean toward the Americas.

More nonlinear trends are emerging from recent climate data, showing that global warming is increasing. As a result, we may be further behind in adaptation and mitigation than we thought. “That’s deeply disconcerting, but it’s important to face those possibilities,” said Horton.

Horton warned that we may start to see concurrent nonlinear trends in other areas. Real estate values could drop precipitously because of sea-level rise or repeated flooding, and food prices could spike because of frequent agricultural disasters. “And who the heck knows what the failure to have proper winters, like this year, is going to mean for our ecosystems?” he asked. “We’re in uncharted territory.”

There are positive nonlinear trends: The price of installing wind and solar power has fallen faster in the past 10 years than anyone predicted, and there’s been an increase in people purchasing electric vehicles. Other positive trends will take time to appear as legislation takes effect, electricians are trained and networks of EV chargers come online. But Horton says we may be approaching or have reached critical tipping points, even if we aren’t aware of them.

Charts by Climate Central (climatecentral.org)

Thank you for reporting on this critical issue. We are fortunate to have a great source of knowledge right here in Philipstown. Dr. Radley Horton will speak at the Desmond-Fish Public Library at 2 p.m. on Saturday, April 6, for anyone who wants to learn more. He will be interviewed by David Gelber.

Much of the conversation around global warming focuses on how changes in temperature and precipitation are going to be unpleasant and inconvenient for individuals but, and this article touches on it, the real challenges will come from the array of nth-order effects like crop failures and food shortages, long-term power and communications outages, population displacement and mass migration, supply chain disruption, and civil unrest. Throw in the far-reaching implications of A[G]I, and its enormous energy consumption, and we may face a future that is extremely unlike the present.

We’d be well served to move on from the bargaining stage of climate grief to an acceptance of the fact that the dominoes are already falling, that our unmitigated, ecologically blind consumption and the imperative for economic growth is the cause, that the fragile and complicated systems that underpin our modern Western lifestyles will not endure, and that it may fall upon individual communities to ensure that their residents can survive and thrive in the future.

I highly recommend Nate Hagens’ The Great Simplification podcast and the books Surviving the Future (excerpts from David Fleming’s Lean Logic) and Rob Hopkins’ From What Is to What If for some visions into what our future will/can look like. If any Beacon residents are interested in discussing/working toward a more resilient local future, join me and others at future.beaconny.net (email [email protected] for an invite).