Two-person show of works by married artists Adrienne Cullom and Sergio Gonzalez-Tornero

By Alison Rooney

The artistic worlds of the North American South and the South American South were united in Paris in 1960 when Chilean Sergio Gonzalez-Tornero met Atlantan Adrienne Cullom in a printmaking workshop. “I was full of ink, up to here,” recalls Gonzalez-Tornero, “but I washed my hands a bit, we went to a café for coffee and baguettes,” and now, more than 50 years and three daughters later, the couple is paired again in a joint exhibit at Cold Spring’s Marina Gallery. Cullom, an engraver, water-colorist and fiber-mask maker, is displaying her distinctive knotted masks, while Gonzalez-Tornero’s modernist paintings, inspired by the Haida peoples of the Pacific Northwest, are on view.

Between them, Cullom and Gonzalez-Tornero have exhibited around the world, in solo and group shows, and their work is held in many private and public collections. Their time in Paris concluded with Gonzalez-Tornero following Cullom to Atlanta, and then, in the usual 1960s progression, to a small railroad-flat apartment in Greenwich Village where they and their growing family vied for space with their artistic pursuits.

Fate intervened when Gonzalez Tornero’s publisher visited the basement of their Manhattan home and questioned how they could live and work there. He insisted that they go and live in his vacation place in Mahopac, making them an offer they couldn’t refuse: “Work there and you can buy my house in Mahopac in exchange for prints.” Hundreds and hundreds of prints later, the home became theirs, and Mahopac has been their residence since 1970. Cullom adds, “And the car we have now was in exchange for a painting!”

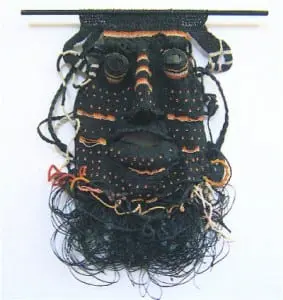

It was Cullom’s long stretch working in black and white that inspired her wish to switch to color. She described the beginnings of her mask-making: “With my engravings, I started doing 3-D work. Then I began to learn how to knot, with an eye to dying the work myself. I took out a book and started practicing knots. There were some 3,000 to learn, but unless you’re going to run off with a sailor … it wasn’t necessary for what I do to do all those other knots … I had worked before in clay and with cast heads — the bare minimum of sculpture … It started as a process; working from the house I started with these inspirations, things just in my head became the process of doing something.”

When Cullom begins to make a mask, she has no idea how it will turn out. “I don’t even know if it will be a profile, or if it will have two eyes,” she says. “I start, and see what happens. I give them titles long after I’ve knotted them. I see them as masks to view the world.” Their very evocative titles include Mask for Political Discourse and Mask for Enjoying Long and Sultry Summers.

Cullom begins with a board to which she affixes a stick to hold the strings, making sure all begin at an even length, secured by even numbers of square knots. “The fun is to end up with extra eyes, an odd nose, tufts of hair — you have to add more string.” She characterizes the masks more fully with found materials: her grandmother’s beads, old shirts yielding unusual buttons.

The smallest masks take Cullom about a year; the bigger ones much longer. “You don’t just knock them out,” she says, wryly, “however, I’m a Speedy Gonzalez if you look at other arts which take years. Engraving is also a very slow process. Maybe slow processes give me time to think.”

In notes for the exhibition, Gonzalez-Tornero describes his work as a “fusion of two distinct things: a compulsion towards modernist form and a fascination with the historic cultures of the Pacific Northwest. I respond to their art above all, which I see as a deeply spiritual and gloriously formalist view of life.” Invited, years ago, to visit a Canadian friend who was living in what are known in colonial terms as the Queen Charlotte Islands, an archipelago located off the coast of British Columbia, Gonzalez-Tornero was immediately entranced by what the aboriginal people call Haida Gwali. “To me the place had magic; I was captivated by it and have returned six times,” he said.

While reading a book of Haida myths and stories, he discovered a character, “The Chief of Kloo,” and zeroed in on him. Transporting the words through the prism of his paintings, he sees the Chief of Kloo as “a dramatic character, a geometrical personage defined by intersecting straight lines most convenient for the construction of hard-edged, articulated color spaces.”

Asked if the masks and the Chief of Kloo seem to get along, sharing the space of the Marina Gallery as they do, both artists immediately assented, Cullom pronouncing it “amazing that string and paint get along!”

The exhibition concludes its August run this Saturday, Aug. 26. The works are on view Thursday to Sunday from noon to 6 p.m. or by appointment. The Marina Gallery is located at 153 Main St., and the phone is 845-265-2204, or visit their Facebook page.

A wonderful review for two lovely artists. I’ve seen their work through the years and it just gets better and better.