Effort aided by wisdom from Baldev Raju, who assisted Russel Wright in 1970s construction

By Alison Rooney

Manitoga’s 75 acres of woodland trails, outdoors ‘rooms,’ ponds and native plantings require far more maintenance than what the small landscape staff is able to manage. The usual tasks of weeding and clearing are dependent on the good will of a coterie of volunteers, many devoted to the site after visiting as hikers, or on a tour of the home and studio, or both.

Four times a year Manitoga rounds up these ready, willing and able-to-help volunteers and enlists their assistance in a specific, targeted project. Recently, on a perfect autumn Saturday morning, the contingent was put to work in at what – during more rain-flush times – is one of Manitoga’s signature spots, the Russel Wright-designed waterfall, which flows into the carved-out-from-granite pond which the home and studio overlook. During peak water flow times, resounding cascades of water thunder down from streams above.

What makes it unique beyond the obvious visual and aural beauty, is that it did not exist as it is now, originally. When Russel Wright designed the home and landscape, he carefully worked out a plan to create the waterfall, using a combination of heavy-duty equipment and old-fashioned manpower to divert several streams from just north of the pond, so that they would empty themselves into the pond.

To achieve just the precise flow and rushing water sounds that he wanted, he carefully calibrated a path of boulders designed to guide the water, at times having giant, heavy stones moved just slightly, to achieve his vision.

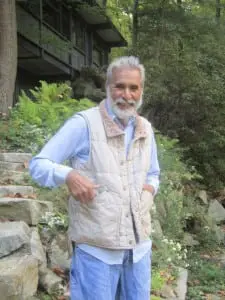

Assisting him in this labor was Baldev Raju, then (around 1973) recently arrived in Garrison, and badly in need of a job. Raju, who still lives in Garrison, came along on this volunteer day, ostensibly to offer advice, but in reality literally pulling up his sleeves and helping once again to set the waterfall right. He recounted the story of how he helped the first time around:

“I was looking for a job. I asked my friend, who was a friend of Russel Wright, ‘Can you get me work?’ She talked to him and he said ‘yes, I need someone who can help me.’ He liked my idea of helping with stonework, landscaping and bookkeeping.

“I was happy to have the work — especially as I had no good experience in anything! I learned everything from him: cooking, moving trees, cutting stone. I lived in the big house; he lived in the studio. We had breakfast together every day and then went to work. We always had music on while we worked in the pond: Indian music, classical, Japanese. I stayed until 1976 and then worked a little longer after that — for five years we worked together. Then there was no longer any money to take care of things, so I had to leave.

“He wanted to make it as natural as can be — the waterfall, landscaping, paths. We walked so many days and months to see and always tried to follow the natural paths, keeping it as much as possible the way it is in nature, bringing more native plants, letting the people know the ways that nature comes and goes.”

As volunteers arrived in the morning, Manitoga’s landscape manager, Emily Phillips, gathered them round a display of photos showing the waterfall and surrounding area as they used to be. She explained that the area, devastated by recent hurricanes, was no longer functional. Describing the work of the day as “highlighting the water course” she noted the need for pushing rocks over to the side, building up the course again to see where water enters the pond.

Vegetation clearing was also needed. “At the top there’s a pool,” said Phillips. “It has a breech in it. We can try to push the gravel out – it just needs clearing. We’ll have one team up there, and another at the edge of the pond, so we can start to see our pond looking deeper, and not like a marsh.” Raju, speaking words likely similar to those he heard from Wright decades ago, added to the directions: “You have to build a stone wall around the other side. And the spicebush should be cut down so people can stand over there and see the view.”

Manitoga’s Executive Director, Allison Cross, was there helping, along with her husband and two young children. She called the Landscape Volunteer Days “integral to our mission, which is to preserve and share Manitoga — which is the entire property: the house, studio, woods, trails — with the public. The work is done in tandem with our Woodland Landscape Council. We invited Baldev here a month ago because we had some questions since we don’t have everything documented. He immediately said that the water course was off. He talked eloquently, saying that the waterfall was part of the [outdoor] ‘Living Room’ and an important part of Russel Wright’s intent, so that it was important to maintain.”

Manitoga’s Board President, architect David McAlpin, was also hard at work near the pond. “One of Russel Wright’s interests was to bring Americans into a closer and intimate relationship with nature,” he said. “Hopefully the people participating here today can take something that they’ve learned home and apply it — and have fun, too. McAlpin noted: “It’s easier to notice when the interiors begin to degrade; it’s more difficult with the landscape.”

Volunteers came from far and wide, and included two women, Anita Csordas and Annie Block, from Brooklyn. Csordas, an interior designer, “came up here last summer, hiking with my dog,” she said, “This is a great opportunity to help and get my hands dirty. It’s a mutually beneficial deal: seeing nature.” It was Block’s first visit to Manitoga.

Ironically, she had been scheduled to come for the public tour on what turned out to be the day that Hurricane Sandy hit. “We always knew we’d come back,” said Block, the deputy editor at Interior Design magazine. “Interior Design has a deep interest in Russel Wright, and this is so fortuitous because now we’re helping out with what resulted from the destruction of Sandy. Russel Wright is a mid-century master and our magazine cherishes him. It’s a beautiful fall day, and it’s wonderful to be here. This is just such a masterpiece and we want to help preserve it.

Manitoga’s next Landscape Volunteer Day will take place from 9 a.m. to 2 p.m. on Saturday Nov. 2. Lunch is provided. For more information or to register, visit russelwrightcenter.org or phone 845-424-3812.

Photos by A. Rooney