In a national survey conducted in September by Marist Poll for National Public Radio and PBS News, 44 percent of registered voters said immigration was a deciding factor in whom they support for president. Another 43 percent said it was an important factor. In this series, we examine what drew recent immigrants to the Highlands, the process they undergo to stay and the effect on local schools.

When Renata Saldaña was 17, she and her younger sister showed up at the Garrison School seeking to enroll. It was 2017 and they had just come from Ecuador, overstaying tourist visas and moving to their parents’ Philipstown apartment.

As Renata recalls, it took a week to realize that they were at the wrong school, that Garrison only goes through eighth grade and that they needed to enroll a few miles up Route 9D at Haldane High School.

“We spoke no English,” she said, adding that the schools sometimes relied on Spanish-speaking janitors to translate. “It was hard.”

That year Renata and her sister were two of 11 English Language Learners (ELL) at Haldane and the only two enrolled at the high school. The district had one ELL teacher.

Seven years later, Haldane has 20 English Language Learners among its 800 students and has added a second ELL teacher, said Carl Albano, the district’s interim superintendent.

What’s happening at Haldane is happening at schools across the Hudson Valley.

In the Wappingers school district, the number of ELL students has tripled over the last 10 years to more than 330, although that’s still a tiny percentage in a district with over 10,000 students, said Michelle Cardwell, assistant superintendent for curriculum and instruction. She said the growth of the ELL population has not strained district resources. The Arlington, Brewster, Carmel, Poughkeepsie and Newburgh districts report similar increases.

Driving the growth are people fleeing economic hardship and political turmoil in Latin America, said Julie Sugarman, associate director for K-12 research at the Migration Policy Institute in Washington, D.C.

At Haldane, 50 percent of the English language learners are Latino, according to state education data. In Beacon, it’s about 80 percent Latino, in Wappingers, about 75 percent, and in Poughkeepsie and Brewster, about 95 percent.

Newburgh had 1,800 ELL students last year, up from 1,500 a decade ago. The district reported that most newcomers are from Honduras, Peru, Columbia, Venezuela, Guatemala and Haiti. In Wappingers, many are from Guatemala.

An exception to the ELL growth is the Beacon school district, where enrollment has remained consistent: 75 a decade ago and 70 today among the district’s 2,400 students. The reason is the cost of living, said Sagrario Rudecindo-O’Neill, the assistant superintendent of curriculum and student support. “If you look at the rents here, you can’t buy anything,” she said. “We don’t have hotels nearby or short-term rentals.”

Kathryn Lokmaci, who teaches ELL at South Avenue Elementary School, recalled that several years ago some ELL students were forced out of their homes on Main Street to make way for condos and “had to relocate to other areas that were cheaper, like Newburgh or Poughkeepsie,” she said. “That was sad.”

How many ELL students are undocumented is unknown. Districts enroll students without regard to their legal status; the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1982 in Plyler v. Doe that public schools must accept undocumented immigrants.

That case was in the spotlight last year when some New York districts expressed concern about an influx of immigrants. In response, Attorney General Letitia James and Betty Rosa, the state education commissioner, issued a joint letter “to remind school administrators that all children and youth in New York between the ages of 5 and 21 have the right to a free public-school education,” regardless of status.

The influx has created a shortage of ELL teachers, prompting the Education Department to partner with local teaching programs and to build flexibility into the certification process. The department said that more than 1,400 people have enrolled in ELL teaching programs over the past decade.

In recent years, Wappingers added four ELL teachers and now has 12, said Cardwell. She noted that several districts in Dutchess County have partnered with SUNY New Paltz to get more teachers certified.

In addition to learning English, immigrant students face emotional challenges.

“I felt so ashamed,” said one former Haldane ELL student. She recalled telling her parents: “I’m not happy here. I’m not understanding anything. I can’t communicate with my friends. Coming to school is giving me anxiety. I can’t do it anymore.”

She said she was bullied for her lack of English. The student, who asked not to be identified because she is still undocumented, told her parents that she wanted to transfer to Peekskill, where there were more Latino students.

She credits Principal Julia Sniffen and her teachers with stopping the bullying, making her feel welcome and persuading her parents to stick with Haldane.

ELL students also experience culture shock. A Newburgh student from Ecuador reported that she didn’t understand why students didn’t wear uniforms and was appalled when she saw students attending school in what looked like pajamas.

While the influx of immigrants has created resource challenges for larger districts in New York City, Chicago and Denver, schools in the Highlands appear to have embraced the diversity.

Beacon’s district newsletter, the Bulldog Bulletin, featured a story this summer about a project in Lokmaci’s class at South Avenue called Bilingualism is My Superpower.

“It’s scary when you come to another country, and you might be isolated from your culture,” Lokmaci said. “I want them to know that it is cool that they know two languages.”

Haldane also has embraced cultural differences, said Albano: “It brings a lot of value to the school.”

When she graduated in 2019, Renata Saldaña was the first Haldane graduate to be awarded a Seal of Biliteracy by the state, said Sniffen, who noted that by 2024 a third of the graduating class earned the honor.

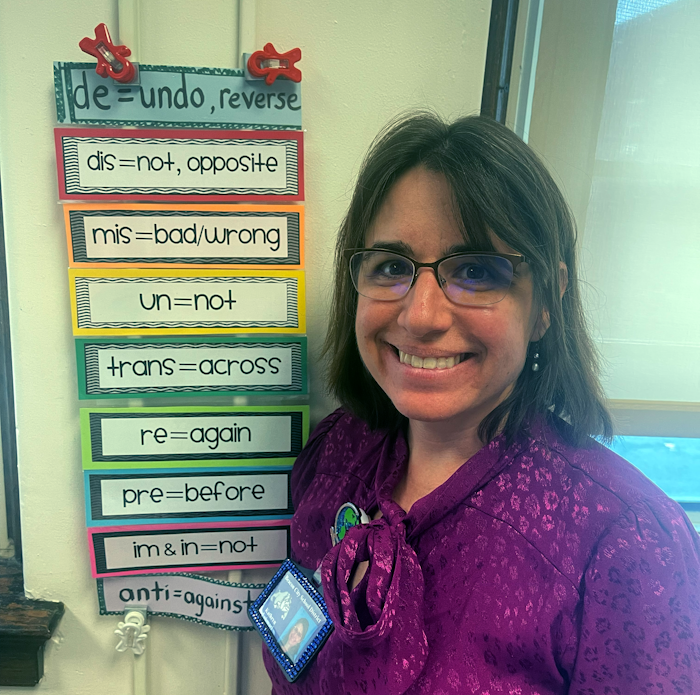

Barbara Jennings, who has taught ELL at Haldane since 2010, said the approach has evolved. Teachers once urged students’ parents to speak only English at home, believing that immersion helped children become fluent more quickly. Now, she said, students are encouraged to retain their native language and culture.

Nevertheless, Jennings said some students shy away from their native language. “They’re embarrassed because it makes them different,” she said. “I try to share with them how important it is to have their identity, to share their culture and to share their heritage.”

Not once in Plyler v. Doe do we see featured the nonsensical term “undocumented immigrant.” We do see “illegal alien” and “undocumented children,” both of which possess merit in context. I continue to urge The Current to de-politicize its reporting and stick to precise usage of language, particularly in cases in which it’s easy to do so. Sadly, The Current’s choice to politicize is exposed as faulty in its very own definition of the term “undocumented” in the Oct. 25 edition: “Since 2013, the [federal] government has issued ‘waivers’ [aka documents]” to illegal aliens.