Cold Spring, Beacon and Little Stony Point conditions generally good

By Liz Schevtchuk Armstrong

Despite notable improvements in recent decades in the cleanliness of the Hudson River, troubling threats persist, notably from sewage and related pollutants, according to a new water quality report by the environmental group Riverkeeper.

But in the Hudson Highlands, reason for optimism exists.

The Riverkeeper How’s the Water? report for 2015, released June 29, focuses on fecal contamination — principally from human excretory waste and animal droppings — and surveys the quality of water in beach areas used for recreation and swimming, as measured against federal Environmental Protection Agency recommendations. By that criteria, the waterfronts at Beacon, Little Stony Point (location of the popular Sandy Beach often used for wading and swimming) and Cold Spring look good overall, the 39-page report indicates.

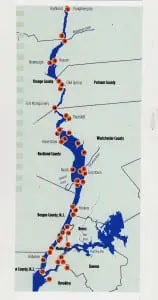

In the report, a chart listing 74 communities and other places (such as parks), where water sampling occurred, depicts water quality calculated on the basis of the EPA’s Beach Action Value, or BAV, for safe swimming and related recreational pursuits. Riverkeeper and its partners in the report, the City University of New York–Queens and the Columbia University Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, tested for enterococcus, which, typically, while not harmful in itself indicates the presence of pathogens — bacteria, parasites or viruses — associated with sewage and related contamination.

At a given location, Riverkeeper explained, a red bar on its report chart shows the percentage of single samples that exceeded an “entero” count of 60, the EPA-recommended BAV safe-beach limit. “Above this level, the EPA recommends public notification and possible temporary beach closure,” the report states.

A ‘blessed’ environment

On the chart, Beacon, Little Stony Point and Cold Spring stand out (along with several other areas) for their minimal red and long swaths of green. The Beacon harbor had a rating of 18 percent in terms of BAV lapses and 82 percent in regard to good water quality. Little Stony Point, just north of the Cold Spring village line, did even better, with a 5 percent score for problems and a 95 percent green, “good” score. Cold Spring’s waterfront slipped slightly behind Little Stony Point, with a 7 percent score for problems and a 93 percent good water-quality rating.

In contrast, at the Newburgh boat launch, across the river from Beacon, the percentage for problems was 61 percent, and the good-water rating 39 percent.

“I’d say the waters of the Hudson around Cold Spring are about as clean as in any stretch of river. Here in Beacon and Cold Spring, we set a pretty high bar,” said Paul Gallay, Riverkeeper president. “It’s good news.” A Cold Spring resident, Gallay told The Paper in a phone conversation Wednesday (July 22) that the Riverkeeper team had taken 42 samples off of Dockside in the last seven years, and only three of those exceeded the levels for safe beaches. At Little Stony Point, of 46 samples, only two exceeded the limit of allowable levels, he continued.

“I’d be very confident getting into the water at Little Stony Point,” said Gallay, noting that he and his family have done so. “Around Cold Spring, we’re blessed,” Gallay said.

Other areas don’t fare so well. “We have water-quality problems in many other parts of the Hudson and its tributaries” where people swim, he observed.

The report covers sites from above the Mohawk River north of Albany to the Gowanus Canal in New York City. It reveals that “23 percent of Hudson River estuary samples fail,” along with those from 72 percent of Hudson River tributary waters and 48 percent from New York City water-access points.

Storm excesses

Contrary to what river-town residents might assume, conditions often worsen with rain — which rather than diluting contamination seems to spread it. “After periods of dry weather, the Hudson River Estuary is safe for swimming in many locations. But after rain, the water is more likely to be contaminated, especially in areas affected by combined sewer overflows and street-water runoff,” according to the report.

It explains that “combined sewers carry both sewage and street water in the same pipes” and that rain or snowmelt can overwhelm a wastewater treatment plant or pipe capacity, producing sewage overflows in facilities struggling to prevent treatment-plant failures. “In the Hudson River Watershed,” according to the report, “there are more than 660 Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO) outfalls.”

Furthermore, it states, “inflow and infiltration” is linked to some problems.

Inflow and infiltration, or I & I, has been a source of concern in Cold Spring, where cases of I & I have involved excess water from heavy rain and other potential sources flooding into the sewer system, overwhelming the sewage treatment plant and forcing discharges into the river. In recent years, the village wastewater treatment staff, led by Water and Sewer Superintendent Greg Phillips, have investigated and tackled I & I causes. The village also anticipates a thorough $1.6 million upgrade of the aging sewage treatment plant on Fair Street, to deal with various needs.

All that notwithstanding, Gallay pointed out that “Cold Spring has safe samplings even after rain.”

Contaminants

Riverkeeper’s report attributes river contamination to such sources as human sewage from leaky sanitary sewers, illicit sewer connections and illegal dumping; dog and other domestic pet droppings; manure from some farming and livestock operations — “the risk from cattle waste is comparable to human waste” — and even decaying plant matter, litter and sediment in storm drains and on streets.

Then there are the problems associated with faulty septic systems. The septic system “failure rate has been estimated at 10 percent nationwide and as high as 70 percent in some communities,” the report states. Many homes in Philipstown rely on septic systems. So does nearly all of the village of Nelsonville, with its close-together houses and other buildings. The report states that “only a handful of communities regulate operation and maintenance of systems at private homes.”

Monetary needs

To help communities meet infrastructure challenges, Riverkeeper advocates a greater New York State government financial role. “The need for investments in wastewater infrastructure statewide, including for managing street-water and farm runoff, has been estimated at $45 billion over 20 years,” the report states. “The governor and [state] legislature need to increase resources for DEC [state Department of Environmental Conservation] and other state and local partners.” It notes that the state has reduced the DEC Water Division staffing by 30 percent in about 25 years and projects substantial DEC budget cuts over the next five years.

Likewise, among other actions, Riverkeeper urges the Empire State to:

- Increase annual wastewater infrastructure funding by $800 million to meet the documented annual need, and exempt water and sewer investments from the 2 percent tax cap to remove a barrier to long-term investment.

- Implement Combined System Overflow Long Term Control Plans, and reinvest where necessary if fully implemented plans fail to result in water quality that meets safe-swimming standards.

- Adopt asset-management strategies, including mapping of wastewater and storm-water systems, so communities invest wisely in maintenance.

- Implement septic management programs to ensure proper operation and maintenance.

Gallay said that the current state budget, which took effect April 1, offers hope. It includes “a new $50 million for wastewater treatment plants and drinking-water safety,” with the money now available for communities to tap, he said. “For that we thank the legislature and governor.”

Riverkeeper’s report can be found online at riverkeeper.org/water-quality.

Photos by L.S. Armstrong

Nobody should be surprised that our open waters are still polluted, because EPA never implemented tge Clean Water Act. When it set sewage treatment standards, it used the BOD (Biochemical Oxygen Denand) test incorrect. By using its 5-day reading (without any nitrogen data), instead of its full 30-day reading, EPA not only ignored 60% of the pollution exerting an oxygen demand, but all the nitrogenous (urine and protein) waste, while this waste also is a fertilizer for algae, hence contributes to deadzones, now in all our open waters. To learn more about this BOD test read http://www.petermaier.net/clean-water-act/bod-test-history-and-description-2

Any attempt during the past 33 years tocorrect this essential test (so we finally will know how seage is treared and prevent that multi-milion dollar sewage treatment plants are not designed to treat the wrong waste) failed, because everybody involved is too embarrassed having to admit that such a basic mistake was and still is made.