Many humans also involved, including Philipstown director

The future of AI-animated film is here — but there are still some kinks that will be resolved when today’s leading-edge technology eventually becomes obsolete.

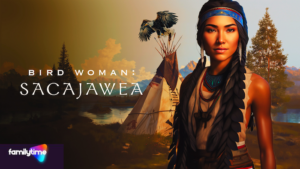

Philipstown filmmaker Lynn Rogoff, who has watched computer-driven movies and video games evolve for 30 years, wrote and directed the first episodes of a new historical series, Bird Woman: Sacajawea, which has already earned an armload of awards and began streaming this month at Familytime.tv.

This is no press-a-button-and-the-magic-occurs process, she says. The feature expanded the capabilities of artificial technology by combining three software tools to create somewhat lifelike historical avatars that speak.

“Getting characters to talk is very hard for AI, so this is a milestone,” says Rogoff. “We’re the first team to combine these applications. When we sent the film to [one of the developers], they were shocked because they thought their product would be used as an enterprise solution, like selling homes on the internet.”

Here, the focus is on influential figures in the Lewis and Clark Expedition, including Sacajawea’s baby, nicknamed “Pompy.” Behind the historical talking (and cooing) heads, backgrounds convey vivid natural dreamscapes and dramatic action scenes that explore the journey’s inherent clash of cultures.

Something always moves onscreen as the characters deliver their lines, and the look is designed to mimic video games, says Rogoff.

The story germinated 20 years ago as a script. Other human elements include voice actors, a haunting flute song, a score crafted by a composer, an orchestration of the score, illustrators, editors, historians and Rogoff’s directing.

“Everyone wanted to work on this because no one ever combined music audio, dialogue and special effects in this medium,” she says.

For two decades, Rogoff tried to drum up funding for a video-graphic portrait of Sacajawea, a teenager who guided the federally sponsored expedition from 1804 to 1806 through the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Ocean and back, infant in tow.

But timing is everything. Now, the atmosphere for the film is more receptive due to the Me-Too feminist movement and a newfound interest in telling stories from diverse communities, Rogoff says.

The reboot started at the Butterfield Library in Cold Spring, where Rogoff revisited the historical record with help from librarians Jane D’Emic and Pat Turner. Then, she headed to her cabin in the woods with the goal of time-traveling to the early 1800s and conveying Sacajawea’s perspective.

Rogoff spends winters in Manhattan, where she teaches communications at the New York Institute of Technology. The school provided a grant to develop chatbot characters from the film to answer questions in real-time (in English and Spanish), drawing from their uploaded knowledge base that includes the film’s script, journals from the expedition and other heavy texts and documents.

Though mature in places (it’s rated TV-PG), the project skews toward an educational market and attempts to make history entertaining for people who chafe at processing names, dates and facts, says Rogoff, an alum of PBS shows Sesame Street and Big Blue Marble.

In the 1990s, she started a nonprofit called Amerikids Productions and worked with then-revolutionary blue screen technology after McGraw-Hill commissioned Pony Express Rider, a history-themed game that delivered doses of information in a palatable format.

Amerikids are icons whose claim to fame occurred during their childhood or teen years, including Sybil Ludington, who was 16 when she made her famous 1777 ride through what is now Putnam County to warn that the British were coming, says Rogoff.

Beyond extending AI’s capability to create characters who speak and make credible facial expressions, the film breaks the technology’s four-second barrier.

“AI doesn’t understand the human body, so after four seconds, legs get weird and fingers kind of disappear,” says Rogoff. “Our team edited hundreds of four-second moments together; that’s state of art, as of now.”

Other limitations include blurred teeth and awkward scowling, smiling and lip movements. But some details can be stunning, such as the creases in characters’ faces, the furrows in the hills and the reflection of a snow-capped mountain in a lake.

“The hardest part of filmmaking is raising money,” she says. “Kevin Costner spent $100 million on Horizon trying to recreate the 1800s. I want to tell an interesting and accurate story and, yes, we’re using AI to make life a lot simpler, more productive and cost-effective. But we’re still bringing human creativity to the fold.”