A young woman chronicles her battle with anorexia

In January 2017, Sandra Slokenbergs wrote in her journal: “I have a sickening feeling my daughter is dying.”

Her fears were well-founded. A week later, her daughter Lidija, 17, a Haldane junior, was rushed to a hospital, suffering from severe anorexia.

Anorexia nervosa is an eating disorder which, if not treated, can cause serious medical conditions associated with starvation. Anorexia is second only to opioid overdoses in deaths tied to mental illness, including by suicide. Its causes are not fully understood but are thought to involve genetics, psychological and social factors and major life transitions.

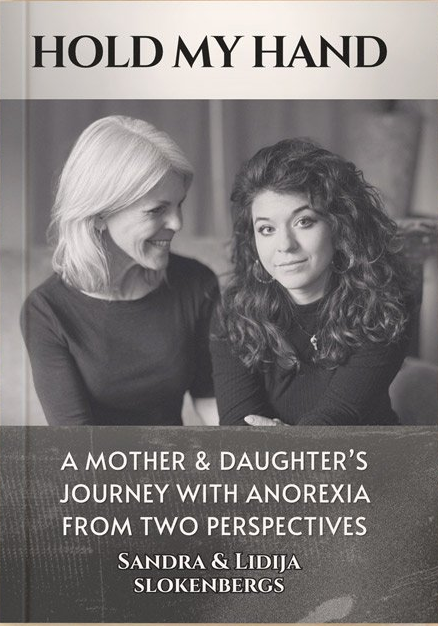

In a newly published book, Hold My Hand, Sandra and Lidija tell their story in detail from each of their perspectives.

By age 16, Lidija had experienced more life changes than most. When she was 6 and about to enter the first grade at Haldane, she and her family moved to Latvia. Both sets of her grandparents had emigrated to the U.S.; her parents were born in New York, but Latvian was spoken in their Cold Spring home.

During the 10 years they spent in Latvia, Lidija changed schools five times. Although Latvia became independent from Russia in 1990, many schools still followed the rigid Soviet system, with multiple daily tests, teachers calling out students’ grades, waiting for permission to sit and an intense level of competition.

“I didn’t feel I could keep up,” she recalled. “I knew I was smart, but I was made to feel stupid a lot of the time.”

Lidija loved to dance but was told at age 12 by her ballet instructor that she danced “like a bear.” She came home crying, feeling “intimidated, ridiculed and never good enough.” There were cultural differences, as well. Although Lidija spoke fluent Latvian, it was with an accent. She was “the American,” an outsider.

The Slokenbergs returned to Cold Spring each summer. Lidija said that was “paradise”: swimming in her grandparents’ pool, her July 3 birthday parties, camp and ice cream. Although she loved Latvia and had friends there, returning was always difficult. Sandra remembers the end of the summers as full of “anxiety, sadness and dread” for her daughter.

Red flags began to appear by the time Lidija was 14. Once, she stood by her bedroom mirror in Latvia sobbing, unable to decide what to wear to a birthday party. Sandra coaxed her to go, but it was a struggle. For a yoga class where everyone wore a T-shirt and leggings, Lidija agonized, rejecting one combination after another.

Sandra noticed her daughter’s movements had become less natural. She had begun to dislike aspects of her body. “Clearly, self-esteem was seeping out of her,” Sandra said. Lidija developed an uncharacteristic interest in Sandra’s treadmill and worked out on it obsessively for several weeks. She later admitted hating every minute of it.

Ironically, a permanent return to Cold Spring in 2016 fueled what would soon be diagnosed as anorexia. “I was happy because I’d have two years left at Haldane,” Lidija said. But other thoughts were troubling. “I felt I had the chance to reinvent myself, to become someone I liked more, someone who was smarter and prettier,” she said. “I had been holding in a lot of stress, a perfect time for anorexia to swoop in.”

Anorexia, she said, makes many false promises: “You’ll be happy if you lose a bit of weight. You’ll be happy if you control your food more. You’ll be happy if you get to the desired weight.”

Lidija’s 16th birthday included a trip to Dairy Queen and an ice cream cake. It would be the last time Lidija ate without feeling the need to greatly restrict food. After eating leftover cake the next morning, she obsessed over the thought that she had already consumed more calories than she should for an entire day. She vowed to take control, to get skinnier, to be prettier. She thought, “Maybe I’ll feel better then.” Her mother recalled: “I saw her change into someone I didn’t recognize.”

Lidija became obsessive-compulsive. She’d swim 100 laps in her grandparents’ pool, even in bad weather or when sick. Soon 100 laps became 120.

Good things happened at Haldane, including a strong performance in the school musical, but to Lidija it felt like “too little, too late.”

She went to a number of counselors without finding a good fit. One, after hearing Lidija’s symptoms, said: “I’d never have guessed — you seem like such a happy person.”

“That comment made me nauseous,” Lidija recalled. She needed someone who specialized in eating disorders. “My body had been slowly crumbling,” Lidija said. “I had been getting dizzy more often and was consistently low on energy.”

In January 2017, a social worker finally recognized what was going on; she said Lidija needed immediate inpatient treatment.

The next evening Lidija remembers a strange blurriness, a feeling of being disassociated from her body and a severe panic attack. Her legs and hands began to tremble. Her father called 911. She would soon spend three weeks at the Center for Eating Disorders at NewYork-Presbyterian Westchester in White Plains.

“I was forced to undergo this massive transformation,” she said. “It didn’t heal me, but it put things into perspective.” Breakfast on the first morning was more than she had been eating all day. Patients earn points for finishing each meal, which allows them to leave their room to participate in programs such as art or yoga.

After being discharged, Lidija continued therapy. Eight years later, “I feel more like myself than I ever have,” she said on Monday (May 26). “I feel more passionate about the things I do, the activities I’ve tapped into. I even speak with more confidence than I used to.”

At the same time, like an addiction, “it’s very easy to slip back into unhealthy behaviors. You have to learn to live with thoughts that don’t always go away.”

Hold My Hand is available at dub.sh/hold-my-hand. If you or someone close to you may have an eating disorder, the National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders operates a weekday helpline at 888-375-7767.