Who’s to blame for these skyrocketing electricity bills? The causes are many: aging infrastructure, economic uncertainty, tariffs, wars, red tape, the failure to build enough renewable energy, inefficient construction, rising demand, the responsibility of investor-owned utilities to generate profits for shareholders and rapidly changing climates, both atmospheric and political.

Over the next few weeks, we’ll examine some of these causes and innovative solutions being proposed. But to understand utility prices, you first must understand how the largest machine in the world works — one so ubiquitous that although we use it every minute of every day, we hardly notice it.

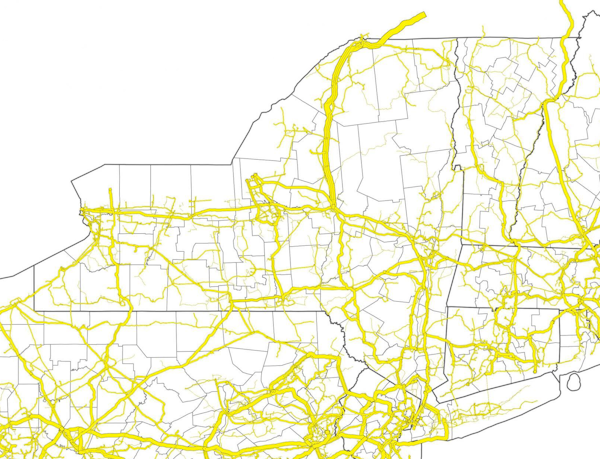

New York’s power grid consists of 11,000 miles of transmission lines that can supply up to 41,000 megawatts of electricity. The problem is that the grid is losing power faster than it can be replaced. Fossil-fuel plants are aging out of service. Since 2019, New York has added 2,274 megawatts while deactivating 4,315 megawatts.

“It’s an old system,” said Rich Dewey, president of the New York Independent System Operator (NYISO), the nonprofit tasked with running the grid, on an episode of its podcast, Power Trends. “The expectation that it’s going to continue to perform at the same high level that it has, say, for the last couple of decades, is just not reasonable. We’re going to need to replace those megawatts” to maintain a reliable transmission system.

The state has undertaken several initiatives to boost the energy flowing through the grid. Six years ago, the state Legislature passed an ambitious law that stipulates that New York must be powered by 70 percent renewable energy by 2030 and 100 percent zero-emission electricity by 2040. Last year, 48 percent of the energy produced by the state was zero-emission; nearly all that energy is produced upstate, where solar and hydropower are abundant.

The $6 billion Champlain Hudson Power Express, which will carry 1,250 megawatts of renewable energy from Quebec to New York City, and passes by the Highlands buried beneath the Hudson River, is expected to go online in 2026. This week, Gov. Kathy Hochul announced her intention, citing the Build Public Renewables Act of 2023, to construct nuclear plants that will produce at least 1 gigawatt.

The site or sites for those plants are expected to be in less-populated areas upstate or in western New York, which would make them subject to the same problem that prevents solar and hydropower from reaching downstate, including the Highlands: a bottleneck where the upstate and downstate grids meet.

The $2 billion question

If Jeffrey Seidman, a Vassar College professor, sounds philosophical when discussing climate change, it’s to be expected. Seidman is an associate professor of philosophy.

A few years ago, he began having second thoughts about his chosen field of study. “Watching the world visibly burning, I began to doubt that continuing to teach philosophy was morally defensible at this moment,” he said.

A career change seemed out of the question — Seidman had just turned 50 — but Vassar’s Environmental Studies department is interdisciplinary. So he developed a class called Climate Solutions & Climate Careers.

Lately, he has been taking his lectures outside the classroom to clear up misinformation for lawmakers. Renewable energy faces strong headwinds these days, as President Donald Trump’s executive orders and proposed legislation demonstrate that he intends to make it more difficult to build wind and solar projects. Before relenting, the federal government briefly halted an offshore wind project that was under construction off Long Island.

At a June 3 meeting of Dutchess County mayors and supervisors, Seidman explained the potential of battery energy storage systems (BESS) to facilitate the transfer of renewable energy from upstate to the Hudson Valley. Jennifer Manierre of the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA) discussed how the state can help municipalities quickly and safely site renewable energy projects. And Paul Rogers spoke about his experiences at the New York City Fire Department, where he was tasked with helping the city develop fire codes for BESS within dense urban environments.

Al Torreggiani, the supervisor for the Town of Hyde Park, was unimpressed. “Where are you going to come in and save me money?” he said. “Because everything you’re talking about is going to cost me money.”

Grid Basics

The U.S. electric grid dates to 1882, when Thomas Edison opened the first power plant at the Pearl Street Station in lower Manhattan. Today, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, plants that burn coal, oil or natural gas create 59 percent of the nation’s energy, nuclear plants account for 18 percent and renewables 23 percent.

To transport electricity over long distances, utilities use high-voltage lines. When the power reaches local substations, it is converted to a lower wattage to be sent to homes and businesses. The national grid includes 11,000 plants, 3,000 utilities and 2 million miles of power lines.

Due to the substantial costs of infrastructure, most utilities are granted local monopolies but are heavily regulated.

At the same time, municipalities are enacting moratoriums on renewables. Last year, Carmel and Putnam Valley passed moratoriums on battery energy storage systems and other projects. In some cases, doubts are fueled by conspiracy theories that wind and solar cause cancer (they don’t). In others, the resistance is for aesthetic reasons.

Battery energy storage systems are needed because solar and wind power suffer from being, to use the industry term, “intermittent.” Fossil fuels may be dirty, expensive and subject to the whims of war, but you can burn them whenever you want. Although the infrastructure costs of solar energy have dropped by 90 percent over the last decade, we have not yet figured out how to keep the sun from dipping below the horizon. Batteries store the excess power collected from solar panels and wind turbines for use when the sun isn’t shining and the wind isn’t blowing.

“As prices [of battery units] have plummeted, it’s made deploying them at the scale where they can support the whole electrical grid more and more feasible,” Seidman said.

The downside is that they can catch fire. In 2023, three BESS units in New York caught fire, including one in Orange County. The state says no hazardous chemicals were released.

Seidman thinks that the risks and dangers have been overblown. During his talk on June 3, he explained how battery units are becoming safer and more affordable. Like solar, battery costs have come down 90 percent over the past decade. He noted that 15 years ago, cellphones caught fire.

“The reason you don’t read those stories is because we have gotten so much better at making these things,” he said. “Even though billions of people carry them in their pockets, they don’t catch fire.” Likewise, the batteries that power electric vehicles have also gotten safer. According to the U.S. National Transportation Safety Board, a gas-powered vehicle is 60 times more likely to catch fire than an electric one.

Paul Rogers, the former FDNY lieutenant who spoke at the June 3 meeting, explained the increasingly rigorous safety testing that battery storage units undergo, including making sure that if one battery catches fire, it doesn’t spread. Several firefighters attended the meeting to hear about training programs for fighting BESS fires (water isn’t effective) and to develop site-specific emergency plans.

In the Hudson Valley, there’s not as much open, available and affordable space for wind and solar projects. But with battery storage units, the downstate grid could receive the ample renewable energy from upstate to replace closer but more expensive and dirtier fossil-fuel plants. With battery units in place, renewable energy could be sent downstate at night, when transmission rates are cheaper and the grid is less crowded.

That is one answer to the “Where are you going to save me money?” question: Renewable energy sent to battery storage units could lower the “supply charges” section of electricity bills. In addition, with battery storage units, utilities don’t have to spend as much on substations and transmission lines, costs passed on as “delivery charges” on customer bills. A recent NYSERDA study showed that putting 6 gigawatts of battery power in New York by 2030 would save ratepayers across the state $2 billion.

At no point in Seidman’s talk did he mention climate change or the state climate laws. That’s intentional. Seidman said it’s easier to explain the benefits of the transition to renewable energy by focusing on less pollution and lower bills, which everyone wants. Some elected officials at the meeting discussed using BESS moratoriums to collaborate with the state on creating guidelines, rather than rejecting the technology outright.

What if your house was the battery?

Imagine you own a department store with an oversized parking lot that is full only one day of the year: Black Friday. As it happens, there’s another lot next door that’s always empty, including on Black Friday.

You ask your neighbor if, on Black Friday, your customers can use his parking lot. Sure, he says, for $1,000 per car. He says he needs that much to pay his property taxes, since the lot is otherwise empty.

Sounds ridiculous? In a nutshell, that’s how the electrical grid works. For 360 days of the year, the grid has enough power. However, on peak days — such as during this week’s heat wave — it requires more. So, operators turn to “peaker” plants, such as Danskammer, located on the Hudson River north of Newburgh.

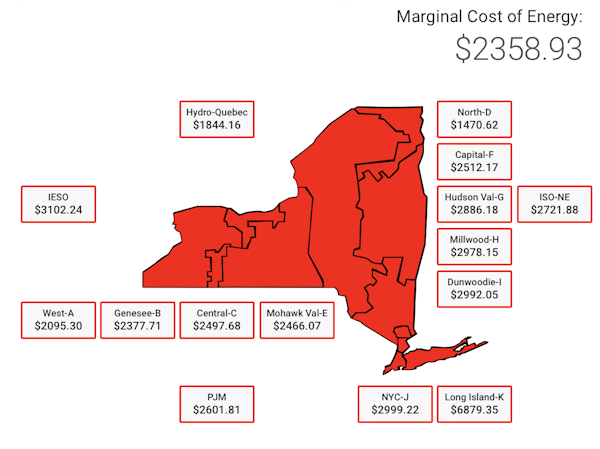

Because these fossil-fuel plants operate only a few days a year, they charge exorbitant rates to cover their operating expenses. That drives up costs across the grid. For example, on Tuesday (June 24) at 5:51 p.m., with the peaker plants running, the price per megawatt in the Hudson Valley was $2,886. A month earlier, on a mild May afternoon, the price was $26.

A few months earlier, the cost in the Hudson Valley at the same time was $26 per megawatt.(Source: NYISO)

These plants release copious amounts of pollution on days when air quality, because of the heat, is already poor. In addition, they tend to be built in low-income neighborhoods.

What if, on Black Friday, instead of paying an exorbitant rate to rent your neighbor’s lot, you coordinated with customers so they didn’t all show up at 6 a.m. when the doors opened? If they did that, you could lower your prices even more.

That’s the concept behind virtual power plants. Electricity customers join a program in which a smart meter in their home or business distributes energy, so that everyone is not using the grid at once. That allows operators to “reduce the peak and those extraordinarily high costs,” said Seidman. Like battery storage, it’s a way of getting more power from the grid without having to build costly substations and transmission lines.

Many people with EVs plug their cars in when they return home for the day, so they will be charged in the morning. With a virtual power plant, a utility can spread out the charging of cars, saving it for the middle of the night, when power is cheaper and the load is lighter. The same can be done with water heaters — after your morning shower, you don’t need your water to be hot again immediately.

Homes equipped with solar panels and battery storage can create their own peaker plant. When the grid needs more power, it draws from the battery unit instead of relying on a more expensive fossil-fuel plant.

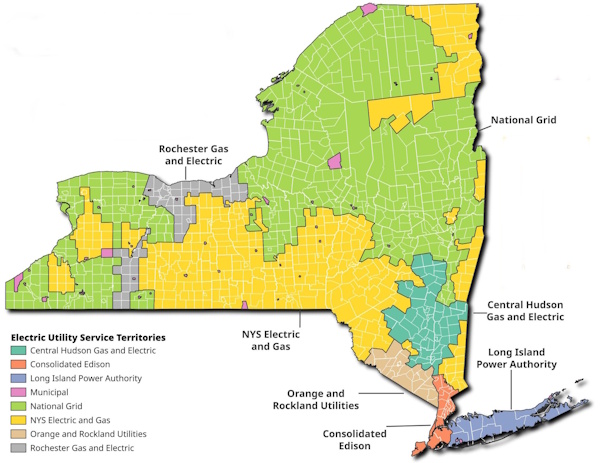

“We call it a virtual power plant because we’re calling on all these smaller batteries to give us the power of a much larger system,” said Christian Woods of Orange & Rockland Utilities, which operates across the Hudson River. “It’s not a big eyesore installation that takes up a lot of space. It’s diluted across the system.”

During this week’s heat dome, customers participating in the Orange & Rockland virtual power plant fully charged their batteries thanks to ample sunshine. At night, O&R drew from those batteries and dispatched about 1.6 megawatts into the grid. On a day when the grid statewide was carrying more than 30,000 megawatts, 1.6 MW might not seem worth the trouble. However, that came from just 346 of the 300,000 homes O&R services in the two counties.

Orange & Rockland launched the program in 2015, when New York State offered funding to utilities that developed methods that cleaned up the grid while lowering costs for customers. Virtual power plants were moving from theory to practice in California and Texas, where they are credited with eliminating many of the rolling brownouts and blackouts that plagued the states due to insufficient power.

After receiving funding from the state, O&R developed a system in which new customers of Sunrun, a rooftop solar installation company, received a free battery storage unit if they agreed to allow the utility to draw from it during peak periods. If there’s an “outflow,” the customer receives a bill credit.

Solar systems are designed to provide up to 110 percent of a home’s annual usage, Woods said. There are seasonal fluctuations in energy usage, “but once you go through a full year, you’ve built up enough credits that you don’t need to buy energy from us,” he said.

Woods called it a win-win-win situation: Sunrun got new customers, O&C didn’t have to build substations and ratepayers got a free battery and lower bills. He said the most challenging part about implementing the program was convincing customers it wasn’t a scam.

Not everyone was eligible for the program: It was only for new customers who had roofs that could support solar panels and got enough sunlight, and who had garages with room for a battery. But Woods said the pilot program provides valuable data. “We’re seeing how much energy is being released through these systems and trying to extrapolate from that,” he said. “What if we had one in every 10 homes? In every five homes? We can take that data to our regulator and say, ‘This is what we’re looking to spend, and this is the benefit.’ This can defer the need to build out traditional infrastructure.”

Together, battery storage and virtual plants could be the solution to preparing the grid for the renewable energy era without raising rates. For that to happen, the state and utilities will need to develop plans that benefit a broader range of people. Even as the mayors and supervisors in Dutchess County warmed up to the idea, there was still skepticism.

“Does Central Hudson have to be involved with any of this?” asked Torreggiani, the Hyde Park supervisor, pointing to photos of battery storage units that Seidman had projected on a screen. “Because they’ll just jack the shit out of the price.”

Part 2: Cost Overload

Part 3: Home Energy

Part 4: Public Power