Beacon resident transcribes soldier’s wartime letters

On Nov. 27, 1944, three days after his 20th birthday, Pfc. Edwin “Buster” Johnson was killed instantly by a sniper in the village of Kriegsheim in northeast France.

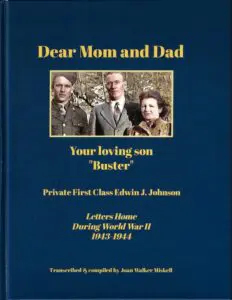

Eighty years later, in time for Memorial Day, Johnson’s 103 wartime letters to his family in Beacon have been published in a book, Dear Mom and Dad.

Johnson’s mother, Mary Moranski Johnson, kept the letters for decades in a trunk. In 2023, her daughter, Anne Johnson Thomas, loaned the collection to Joann Miskell, who had chaired the Veterans Banners Project spearheaded by the Melzingah Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution.

Miskell began to transcribe the letters, which were written in pencil, but many took time to decipher. “They had badly faded, but with a magnifying glass, sunlight and digital editing [to adjust contrast], I was able to get through them,” she says.

When Anne Thomas, 85, read the manuscript, she says she “felt like my brother was still alive and talking to me.” The last surviving of the six Johnson children, she is a longtime volunteer at the Castle Point VA Medical Center in Wappingers Falls.

Buster’s letters, written in 1943 and 1944, chronicle his 19 months in the Army, from his enlistment in Beacon and processing on Long Island, through training in Kentucky and Maryland, to deployment to England and France.

In one letter, he wrote: “We’ll dig fox holes and crawl in and let tanks drive over us.” Says Miskell: “I can only imagine how his mother felt” reading that.

While in Kentucky, Buster married his high school sweetheart, Dorothea Tompkins, 16. He wrote: “If you buy me anything for Christmas, Mom, I wish you’d buy something Dot and I both could use and send it to her. That way I’d have it when I come home.”

Buster’s letters while in the U.S. included descriptions of basic training and camp life. Once overseas, the correspondence became less frequent and was heavily censored to ensure it had no details that might benefit the enemy, such as a unit’s location, movements or engagements. While in France, Buster never mentioned combat but hinted at it, frequently commenting he’d “been very busy lately.”

Below are excerpts from a sampling of Johnson’s letters:

From Kentucky

June 9, 1943: “I’m learning to fire two rifles, 33mm and 50mm machine guns, and a 37mm anti-tank gun. We take long hikes carrying full packs and guns weighing about 70 pounds.”

June 12: “I like Dorothea Tompkins a lot. I’m seriously thinking of becoming engaged. Of course, I want to know what you think. She’s willing to become a Catholic.”

June 14: “I’m dead tired. I never realized I could be so tired.”

July 2: “Three guys went AWOL. They caught one of them.”

July 10: “The Chicago Cubs are playing an exhibition game here against the post team.”

July 12: “I was sent to the rifle range yesterday. I didn’t do too good. I was scared. I couldn’t hold the rifle steady because I was shaking. Today I was better.”

Aug. 11: “Boy, it’s hot and crowded at service club dances. You’re soaked with sweat. I stayed 15 minutes. There’s 15 guys to each girl. You’re lucky if you get to dance two steps with a girl.”

Aug. 14: “Gee, this food is getting worse every day.”

Aug. 30: “I got your letter with pictures of Joe DiMaggio and your package. The cakes are already gone.”

Aug. 30: “I got your letter with pictures of Joe DiMaggio and your package. The cakes are already gone.”

Sept. 11: “We’re going out to the assault course; we crawl on our bellies with machine guns firing over our heads. It’s going to be tough, but I guess I can take it now.”

Dec. 15: “Today we are out in the field. Some of our men dressed as Germans, and we had to attack them. Boy, that machine gun is heavy when you carry it for a while.”

Dec. 25: “I hope everyone is well and happy this Christmas. I went to midnight Mass. Right now I’m on guard at the stockade. I stand in the tower outside the prison fence and make sure no one tries to climb it. The weapon they gave me is a 12-gauge shotgun.”

Jan. 28, 1944: “I had my first boxing bout. I finished my man off in the third round. He couldn’t take it anymore.”

Feb. 11: “Last night we had a beer party. Gosh, it’s too bad I don’t drink beer. They had a few Cokes for us weaker men who couldn’t take the beer.”

From England

May 1944: “I’ve finally arrived safely in England after a trip that wasn’t so bad as I thought it’d be. The scenery is really beautiful.”

June 7: “I received a letter from Dot; she said [uncle] Frank had been home. Tell him I’ll meet him in Berlin pretty soon. Now that the invasion has started, things may start popping.”

June 28: “When it’s not raining, it’s getting ready to. I’ll be glad to get back home again when the war is over.”

From France

July 11: “I’m now in the 79th Division fighting here in France. It was one of the first to enter Cherbourg when it was captured. So, you can see I’m with a good outfit.”

Sept. 8 (to his sister, Marion): “I received your pictures. The boys here were surprised I had such a good-looking sister. They all plan to stop at Beacon after the war.”

Oct. 14: “I went to Mass and communion in a small French church. It looked like it had been very pretty. Now there’s nothing much of it standing.”

Oct. 28: “I was able to see a USO show, The Puddle Jumpers. It was pretty good.”

Nov. 8: “How is everyone at home these days? I’m feeling fine. I’ll write to you again as soon as I can.”

Buster did not write again. His mother wrote three times, noting in each he had not written in some time. On Dec. 3, she wrote: “I keep wondering if you’re not in the front lines.” The letters were returned, unopened.

On Dec. 8, she received this letter:

Dear Mrs. Johnson:

I have been directed by the regimental commander to write these few lines to express to you the profound sympathy of the officers and men of the regiment in the loss of your son Private First Class Edwin J. Johnson, who was killed in action November 27, 1944, while fighting as a member of this organization during the campaign in Western Europe.

Your son was buried in a military cemetery in France. A chaplain of the Catholic faith officiated at the burial. Security regulations forbid revealing details with regard to the exact time place and circumstances of your son’s death.

Although words can in no way decrease or soften your sense of loss, I write these few lines to assure you that he died bravely, and that his regiment deeply mourns the loss of a soldier who so courageously gave his life for his country.

Through your sorrow we hope you will understand our pride in his heroism and devotion to duty.

Sincerely,

Emmit A. Joyner

Ass’t Adjutant

On Nov. 17, 1945, Buster was posthumously awarded a Purple Heart. He was interred in the military cemetery in France until 1948, when his remains were returned to Beacon for burial at St. Joachim’s Cemetery.

Dear Mom and Dad is available by emailing [email protected].

Thank you for your wonderful article featuring Edwin “Buster” Johnson’s letters home during World War II. I am grateful to his sister, Anne Johnson Thomas, for entrusting me with her brother’s precious mail.

On Memorial Day, Anne and I sat together at the Veterans Memorial Building in Beacon remembering him and honoring all the men and women who gave their lives so that we can remain free.