When discussing local history, I always refer to the Highlands as one of the birthplaces of the modern environmental movement. The movement has many mothers. One of them is in North Carolina.

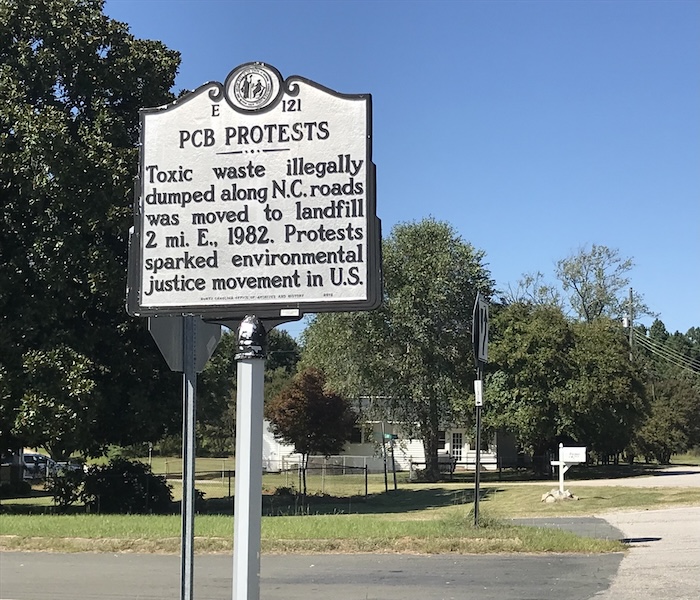

In 1978, a Raleigh company disposed of 30,000 gallons of industrial waste by dumping it on the rural roads of Warren County, which at the time had the state’s highest percentage of Black residents, many of them with limited incomes. Although the waste was cleaned up, the state announced that the waste would be moved to a landfill to be built nearby. County residents began years of protests.

Just as the battle over a plan to plant an electric plant in the side of Storm King inspired the idea of environmental law, the fight in Warren County inspired the idea of environmental justice.

There had been earlier movements: Caesar Chavez’s mobilization of Hispanic farmworkers, a battle in 1968 to prevent a sewage plant in West Harlem, hundreds of years of Indigenous resistance. But the Warren County protests brought the concept to the mainstream, with news photos showing Black protesters lying on dirt roads to block dump trucks of toxic waste. Hundreds of people, including members of Congress, were arrested. The landfill was built anyway.

The idea of environmental justice became even better known in 1990 with the publication of Dumping in Dixie, by Robert Bullard. He wrote the book after learning that, although the population of Houston was 25 percent Black, every single city landfill was in a Black neighborhood. President George H.W. Bush created the Office of Environmental Justice at the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) two years later.

The concept of environmental justice is one of our greatest gifts to the world, but these days, you wouldn’t know it. On Jan. 21, President Trump issued an executive order that attempts to rescind the Biden administration’s environmental justice initiatives. Websites dedicated to environmental justice at the Department of Energy and the Department of Transportation vanished overnight. As of Feb. 6, the EPA’s environmental justice page was still available, although its Climate & Economic Justice Screening Tool is gone. (Researchers who suspected the page might be a target mirrored it at dub.sh/ej-screening-tool.)

It will take time for local and state governments, as well as nonprofits, to assess how the erasure of environmental justice at the federal level will affect their initiatives. New York State has its own Office of Environmental Justice, but the New York chapter of Black Farmers United announced this week that, because of the executive order, it lost key funding and was forced to cancel programs and potentially lose staff.

How might this affect us locally? The toxins dumped in rural North Carolina nearly 50 years ago were polychlorinated biphenyls, or PCBs, the same industrial waste dumped in the Hudson River by General Electric that led to the decades of legal battles over a federally mandated cleanup that so far has not been nearly as successful as anyone had hoped.

What if the world had stood with those Black protesters in North Carolina? Would it have set a precedent that might have helped clean up the Hudson sooner that the 40 years it’s taken, with disappointing results? I was born in 1975 and have lived near the Hudson River for 28 years. The most optimistic current projections state that it will be at least another fifty years before people can eat the fish from the Hudson again without restrictions. When I die, I will have lived my whole life without ever knowing a time that it was safe to fish in the river.

Because of the long history of pollution, negligence and disinvestment, both Beacon and Newburgh are designated in state climate laws as “disadvantaged communities” — and regardless of where you live, anything that happens to the Hudson happens to all of us. As the history of environmental justice has shown, when you start creating reasons that someone else’s home should be a dumping ground, you lay the groundwork for polluters to come to your front door next.