In PCB mess, Hudson recovering too slowly or getting worse

Even as General Electric was dredging the Upper Hudson River from 2009 to 2015 to remove toxic chemicals it had discharged over a 40-year period, environmental groups predicted that the cleanup wouldn’t succeed.

They warned that targets the federal Environmental Protection Agency had set for GE were based on inaccurate measurements that vastly underestimated the amount of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in the riverbed. They said that GE wasn’t dredging the most polluted spots, which would lead to recontamination.

A new report of sediment in the Upper Hudson, commissioned by Friends of a Clean Hudson, a consortium of environmental groups, including Riverkeeper, Scenic Hudson and Clearwater, which is based in Beacon, has borne that out. Samples collected from spots that GE dredged, as well as samples of fish caught in the Upper Hudson, show that the contamination hasn’t decreased as much as the EPA projected it would by this point. In the sampling spot that was closest to the dismantled GE plants that were the source of the PCBs, the contamination has gotten worse.

The conclusion, according to Tracy Brown, the president of Riverkeeper, is that the EPA needs to rule “that this remedy has not been protective.”

(This past summer, after years of delay, GE began a review of the river south of Albany, including in the Highlands, to measure the extent of PCB contamination in the Lower Hudson.)

The release of the study of the Upper Hudson comes in advance of the EPA’s next five-year review of the cleanup, which was supposed to be completed over the summer. An EPA representative would not comment on the Friends of a Clean Hudson report but said the agency’s five-year report will be released in early 2024.

The consortium members are concerned about the conclusions the agency appears to be drawing from the data. “We looked at the same exact numbers that the EPA is looking at,” said Althea Mullarkey of Scenic Hudson. “They’re just not giving it as much importance as we are.”

She accused the EPA of “abandoning the goals that were laid out in the record of decision,” which detailed in 2002 what GE had to accomplish, and switching the focus from risk reduction to risk avoidance.

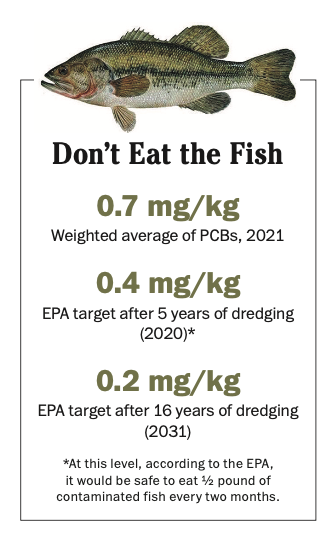

The difference between the two is illustrated in the effects that PCBs have had on subsistence fishing, said Aaron Mair, a Peekskill native who is a former president of the Sierra Club. Many people still fish in the Hudson and eat what they catch, despite state restrictions. Risk avoidance means relying on people who fish the river to not eat their catch. Risk reduction is requiring GE to remove the PCBs that make the fish dangerous to begin with.

The difference between the two is illustrated in the effects that PCBs have had on subsistence fishing, said Aaron Mair, a Peekskill native who is a former president of the Sierra Club. Many people still fish in the Hudson and eat what they catch, despite state restrictions. Risk avoidance means relying on people who fish the river to not eat their catch. Risk reduction is requiring GE to remove the PCBs that make the fish dangerous to begin with.

“What they’re asking Americans to do is write off their river, write off their environmental assets and let corporations convert our most important waterways to a corporate sewer,” he said.

He also pointed out that risk avoidance does not address the ecological damage of the contamination. Bald eagles and river otters, for example, are presumably not following the DEC guidelines.

Only the EPA has the authority to get GE to resume its cleanup, and only if the agency can prove that the dredging wasn’t effective. New York State sued the EPA in 2021 to compel GE to get back in the river. Although the lawsuit was dismissed, the judge wrote that the language of the consent decree “leaves a clear opening for the government to come after the company with the full force of the law to get the job done.”

The consortium believes its new data provides that opening, although Mullarkey said that, so far, the agency “politely agrees to disagree.”

Kevin Farrar, an analyst who worked on the report, said that without more data he couldn’t say exactly why PCBs in the samples were rising, even after dredging.

He did rule out the possibility that they are coming from a source other than GE, although that is probably the case in the Lower Hudson. Manufacturers created distinct mixtures of PCBs during the 50-year period when the chemicals were legal in the U.S.; each has its own fingerprint. “In the Upper Hudson, there simply is no source of any significance compared to GE,” Farrar said.

Scenic Hudson President Ned Sullivan said the consortium would like to see further reduction of PCBs in the river, “but we can’t even begin discussing that until the EPA acknowledges the basic facts, and the failure of the remedy to meet their explicit goals.”

It’s possible the new report will influence the coming EPA five-year review. That’s what happened with the last one, said Pete Lopez of Scenic Hudson, who at the time was a regional administrator for the EPA. He said thousands of additional samples provided by the state DEC and environmental groups painted a more complete picture of the state of the river and the extent of the contamination.

“The EPA was moved from intending to say the remedy was protective to saying that it’s not yet protective,” said Lopez. “This group made the EPA blink.”

It’s so true that people don’t listen to the restrictions on eating fish from the Hudson River. You can cite Environmental Protection Agency data and people will still insist it’s “liberal propaganda” or some other thing or another because they aren’t seeing these stories in the news.

The only way to make conditions safer is not to depend on the actions of people who aren’t hearing about the restrictions (from a source they trust, anyway), but to actually clean the river. [via Facebook]