It’s high season for color and butterflies in my yard. It’s also a good time to check in and notice where I want adjustments. Cut back a species here, move that bee balm over there, fill in a gap.

As I built out my flowerbeds over the years, usually by finding a plant I liked and walking around the yard to find a suitable spot for it, they still have haphazard areas. I overlooked grasses; the flowers caught all my attention.

I made a spreadsheet of native grasses. I had a dozen mixed in with general perennial lists, but moving them to their own category lets me compare attributes and needs. I decided to add ferns and groundcovers; it got unwieldy again, but they have similar functions. Eventually, I’m sure I’ll break them out as I keep adding more and the list gets too long.

Why consider a native instead of an ornamental grass? Miscanthus grasses are among the most widely used and readily available ornamental grasses. Silvergrass (Miscanthus sinensis) has many cultivars with varied sizes and colorations. It is the tall, fountain-shaped grass frequently seen in yards planted as an island or scattered in a row like a hedge with gaps. Some have feathery tips and variegated foliage.

They have been found to jump from our yards into natural spaces, where they compete with native species that our birds, insects and wildlife rely on. Cutting off the seed heads can control its spread. That’s the nicest part, though, and the reason people like them. I don’t think that happens often. Alternatively, native grasses look lovely and make other contributions to the ecosystem.

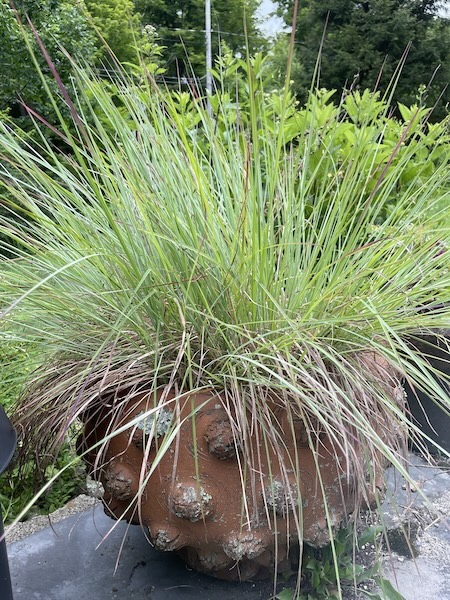

I’ve stuck with little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium) and sedges for the most part. I love everything about LBS — the blue and bronze shading, its graceful form — and it’s a good size to accent and mix into smaller scale projects. It’s a dominant species in short-grass prairies and grows to about 3 feet tall.

Insects and birds love this clump-forming grass, and it is a larval host for the caterpillars of six skippers, a group of butterflies noted for their “stout” bodies and quick, jumpy flying. I typically confuse them with moths. There isn’t any reason not to include a patch of little bluestem in your yard or intermix them with perennials. They even look great in a patio container.

As I’ve broadened my gaze for grasses, prairie dropseed (Sporobolus heterolepis) also has moved to the top of the list. It’s got a waterfall shape, like long hair rolling into the landscape. The seed stalks wave in the breeze and become bird food in the fall and winter, and they get a golden hue. This grass, also a prairie species, thrives in hot, dry conditions. Few cultivars are more compact or have richer coloring, but at 2 feet tall, the straight species is easy to work with.

Moving into some taller species, big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii) can bring the drama. Rising to 5 to 6 feet tall, this grass can take the place of a shrub, be used as an accent or serve as the focal point of a planting. Visualize a cluster framing a view or path. Maybe it’s the column holding the edge of a border or the centerpiece of a mixed-height grouping of perennials. I like to complement it with little bluestem; both do well in dry or medium soil.

I’ve used switchgrass (Panicum virgatum) less frequently, primarily because of a lack of opportunity for the right space. It’s also a 5-foot-tall grass with similar possibilities to big bluestem, but it’s suited for wetter soil conditions. While big bluestem’s coloration falls in with reddish hues, switchgrass is in the yellow spectrum. Both are tall-grass prairie plants.

The grasses I’ve mentioned will all grow well in nutrient-poor situations and appreciate the Highlands’ rocky, clay soil. Maintenance is easy with grasses, and they are best left to brighten the landscape through the winter, providing habitat for insects and wildlife, as well as seeds for birds. Cut them back in the spring to allow new foliage to emerge, although I miss that step sometimes and it still works out just fine. No-pressure plants — there is everything to love about that.