World War II radio operator interred in Wappingers Falls

As the World War II bomber Heaven Can Wait was hit by enemy fire off the Pacific island of New Guinea on March 11, 1944, the co-pilot managed a final salute to flyers in an adjacent plane before crashing into the water.

All 11 men aboard were killed. Their remains, deep below the vast sea, were designated as non-recoverable.

Yet four crew members’ remains are beginning to return to their hometowns after a remarkable investigation by family members and a recovery mission involving elite Navy divers who descended 200 feet in a pressurized bell to reach the sea floor.

Staff Sgt. Eugene Darrigan, the 26-year-old the radio operator, was buried with military honors and community support on Saturday (May 24) at the Church of St. Mary in his hometown of Wappingers Falls, more than eight decades after leaving behind his wife and baby son.

The bombardier, 2nd Lt. Thomas “Toby” Kelly, was buried Monday in Livermore, California, where he grew up in a ranching family. The remains of the pilot, 1st Lt. Herbert Tennyson, and navigator, 2nd Lt. Donald Sheppick, will be interred in the coming months.

The ceremonies are happening 12 years after one of Kelly’s relatives, Scott Althaus, set out to solve the mystery of where exactly the plane went down.

“I’m just so grateful,” he said. “It’s been an impossible journey — just should never have been able to get to this day. And here we are, 81 years later.”

March 11, 1944

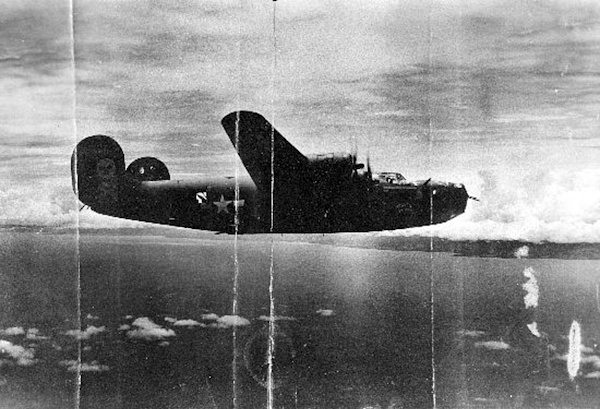

The Army Air Forces plane nicknamed Heaven Can Wait was a B-24 with a cartoon pin-up angel painted on its nose. It was on a mission to bomb Japanese targets. Other flyers on the mission were not able to spot survivors.

Their wives, parents and siblings were of a generation that tended to be tight-lipped in their grief. But the men were sorely missed.

Sheppick, 26, and Tennyson, 24, each left behind pregnant wives who would sometimes write them two or three letters a day. Darrigan also was married, and had been able to attend his son’s baptism while on leave. A photo shows him in uniform, smiling as he holds the boy.

Darrigan’s wife, Florence, remarried but quietly held on to photos of her late husband, as well as a telegram informing her of his death.

Tennyson’s wife, Jean, lived until age 96 and never remarried. “She never stopped believing that he was going to come home,” said her grandson, Scott Jefferson.

Memorial Day 2013

As Memorial Day approached 12 years ago, Althaus asked his mother for names of relatives who died in World War II.

Althaus, a political science and communications professor at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, became curious while researching World War II casualties for work. His mother gave him the name of her cousin Thomas Kelly, who was 21 when he was reported missing in action.

Althaus recalled that as a boy, he visited Kelly’s memorial stone, which has a bomber engraved on it. He began reading up on the lost plane.

“It was a mystery that I discovered really mattered to my extended family,” he said.

With help from other relatives, he analyzed historical documents, photos and eyewitness recollections. They weighed sometimes conflicting accounts of where the plane went down. After a four-year investigation, Althaus wrote a report concluding that the bomber likely crashed off Awar Point in what is now Papua New Guinea.

The report was shared with Project Recover, a nonprofit committed to finding and repatriating missing American service members and a partner of the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA). A team from Project Recover, led by researchers from Scripps Institution of Oceanography, located the debris field in 2017 after searching nearly 10 square miles of seafloor.

The DPAA launched its deepest-ever underwater recovery mission in 2023. A Navy dive team recovered dog tags, including Darrigan’s, partially corroded with the name of his wife, Florence, as an emergency contact. Kelly’s ring was recovered. The stone was gone, but the word “Bombardier” was legible.

And they recovered remains that underwent DNA testing. In September, the military officially accounted for Darrigan, Kelly, Sheppick and Tennyson.

With seven men who were on the plane still unaccounted for, a future DPAA mission to the site is possible.

Memorial Day 2025

More than 200 people honored Darrigan on Saturday in Wappingers Falls, some waving flags from the sidewalk during the procession to the church, others saluting him at a graveside ceremony under cloudy skies.

“After 80 years, this great soldier has come home to rest,” Darrigan’s great niece, Susan Pineiro, told mourners at his graveside.

Darrigan’s son died in 2020, but his grandson Eric Schindler attended. Darrigan’s 85-year-old niece, Virginia Pineiro, solemnly accepted the folded flag.

Kelly’s remains arrived in the San Francisco Bay Area on Friday. He was buried Monday at his family’s cemetery plot, right by the marker with the bomber etched on it. A procession of Veterans of Foreign Wars motorcyclists will pass by Kelly’s old home and high school before he is interred.

“It’s very unlikely that Tom Kelly’s memory is going to fade soon,” said Althaus, now a volunteer with Project Recover.

Sheppick will be buried in the months ahead near his parents in a cemetery in Coal Center, Pennsylvania. His niece, Deborah Wineland, said she thinks her late father, Sheppick’s younger brother, would have wanted it that way. The son Sheppick never met died of cancer while in high school.

Tennyson will be interred on June 27 in Wichita, Kansas. He’ll be buried beside his wife, Jean, who died in 2017, just months before the wreckage was located.

“Because she never stopped believing that he was coming back to her, that it’s only fitting she be proven right,” Jefferson said.