By Ron Soodalter

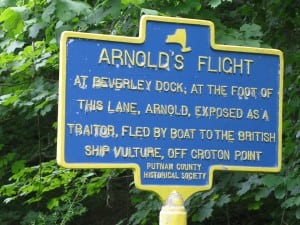

Residents of Philipstown are fortunate to live in an area where so much of our nation’s history took place. One of the most dramatic stories to come out of the Revolutionary War occurred, at least in part, in and around Garrison, and within just a few miles of Cold Spring. It was here that Benedict Arnold – George Washington’s “fightingest” general – attempted to sell West Point to the British. And when the plot failed by the slimmest of chances, it was from here that he made his escape.

Library of Congress

Arguably, there is no other figure in the pantheon of America’s homegrown villains who has achieved the degree of infamy of Benedict Arnold. His very name has become synonymous with the meanest forms of betrayal. And yet, there was a time when he held not only the respect and admiration of a nascent country struggling for its independence, but the love and trust of its army’s commander-in-chief.

The road from patriotism to treason was a long and twisted one, fraught with heroism and injustice, bitterness and disappointment, and deserving of more understanding – and perhaps sympathy – than Arnold has been accorded.

Benedict Arnold was a Connecticut Yankee, born into privilege in Norwich in January, 1741. He learned the value of money, when his father’s bad business ventures compromised the family fortune, and necessitated Benedict’s removal from school. After serving an apprenticeship, he ultimately opened his own apothecary, while maintaining a bustling side business in smuggling. Stocky, powerful, and quick to anger, he reportedly fought two duels before leaving business for a military career.

Apparently, the pull of military service was strong, and just five weeks before the outbreak of the Revolutionary War, he outfitted and trained a militia company, with himself as captain. Immediately after the smoke of battle had cleared at Lexington and Concord, Arnold obtained permission to lead his new company in an expedition against British-held Fort Ticonderoga.

Along the way, however, he was confronted by a man of equally strong and intractable ambition – the legendary frontiersman, land speculator, and brawler Ethan Allen. Allen stood at the head of his Green Mountain Boys (the largest paramilitary group in America at the time) with the same plan as Arnold: seize Ticonderoga. Neither would concede command to the other. Consequently, they agreed to capture the fort together, although bitter feelings between the two remained. Ultimately, Allen would have the last word in his reports to Congress, and would receive sole credit, while failing to mention Arnold’s role – or name – at all.

Arnold was furious over what he rightly perceived as the slighting of his part in the capture of Ticonderoga. He challenged an offending officer to a duel (which the man declined), resigned his commission in the militia, and dismissed his men. This pattern would repeat itself throughout his military career – bold action and the promise of success and glory, followed by disappointment, anger at betrayal by higher-ups, and rash response. It earned him many critics and few supporters, and would ultimately prove his undoing.

By late 1775, George Washington was planning an invasion of British-held Canada, and he proposed Benedict Arnold to the Continental Congress to command an expedition against Quebec. Commissioned a colonel in the regular army, Arnold led his 1,100 men north out of Cambridge, Mass., across icy rivers and into the teeth of brutal Maine snowstorms, on a grueling wilderness trek that has come down as one of the most extraordinary feats in U.S. military history. Hearing of the march, Washington dubbed Arnold “America’s Hannibal.”

On December 31, Arnold and General Richard Montgomery, who had just captured Montreal, launched their attack. The weather was still against them, however, and driving rain and ranks thinned by death and desertion combined to doom their chance of victory. Montgomery was killed, and Arnold came away with a badly wounded leg and dashed hopes. After maintaining a long, fruitless siege at Quebec, Arnold was placed in command of Montreal, but the reinforced British forces eventually rallied and drove the Americans out of Canada. Although disappointed, Washington – in recognition of Arnold’s valiant efforts – had him commissioned a brigadier general.

Meanwhile, Washington knew that the British army in Canada was certain to invade New York by sailing down Lake Champlain and the Hudson River. He ordered Arnold to stop them. During the summer of 1776, Arnold built a tiny armada of 16 vessels, some of which were little more than armed rowboats, and in October, sailed to Champlain to meet the British fleet. Hopelessly outnumbered and outgunned, Arnold lost the two desperate battles that followed, but his bold action delayed the British invasion until the following year. It also gave Washington time to cross the Delaware in the dead of winter, and stage his now-famous attack against Trenton.

Instead of praise, however, Arnold found his name and reputation were in poor standing among many of the politicians in Congress. Nowadays, we tend to lionize the original members of Congress as noble men, unified in their purpose – to forge a new nation. However, they were often self-serving, politically driven bureaucrats, following their own agendas.

The year 1776 has magic connotations for Americans; it was also the year when a political faction hostile to George Washington began a campaign of sniping at him, and all those who supported him. And one way to hurt Washington was by attacking one of his favorite generals, Benedict Arnold. With his prickly personality, and tendency to attract negative attention, Arnold was an easy target.

He was falsely accused of misconduct on the wilderness march to Quebec, and incompetence during the battles on Lake Champlain. And when he learned that Congress had promoted five other brigadier generals – all his juniors, with less experience – to major general’s rank while ignoring him, a disgusted Arnold wrote out his resignation. Only the pleadings of Washington himself, who recognized Arnold as his best fighting man, kept the bitterly disappointed general in uniform.

In the spring of 1777, Arnold led a party of local Connecticut militia in driving a superior British force from Ridgefield to the sea, earning himself the praise of a fickle Congress. They finally promoted him to major general – but did not restore his seniority over the other five appointees. Worse yet, Congress now formally accused Arnold of pilfering goods from Montreal’s merchants during his brief tenure as commander of the city.

Although the Board of War exonerated him, declaring all charges “cruel and groundless,” this time he tendered his resignation – “not out of a spirit of resentment (though my feelings are deeply wounded), but … as an implied impeachment of my character.”

Again, Washington intervened. He had received word that a force of 10,000 British troops under General John Burgoyne had, in fact, invaded the Champlain-Hudson River corridor and was moving on Albany. Washington requested the approval of Congress to send Arnold north to meet the threat, characterizing him as “active, judicious, and brave.”

Congress responded by shelving Arnold’s letter of resignation – but still refusing to restore his seniority. Once again, Arnold was sent into harm’s way, this time to play a major role in the battle that would change the course of the war. And once again, Congress would respond to his victory with insult rather than laurels.

Parts II and III will point out the dramatic events that unfolded just outside our doors and down the road, and will explore the final attacks on Arnold’s character, his marriage to the beautiful young Tory, Peggy Shippen, and his rapid decline from patriot soldier to notorious traitor.