Director investigates the Citizens’ Commission to Investigate the FBI

By James O’Barr

In her well-timed and widely praised documentary 1971, Johanna Hamilton brings us back to those thrilling days of yesteryear, when President Nixon declares the War on Drugs, Apollo 14 lands on the moon, Joe Frazier defeats Muhammad Ali at Madison Square Garden, while the Citizens’ Commission to Investigate the FBI breaks into the Media, Pennsylvania, offices of the Federal Bureau of Investigation and removes all its files.

The Citizens’ Commission to Investigate the FBI? Perhaps some other highlights of that year will provide context: There were 196,700 American troops fighting in Vietnam in the 10th year of that war; hundreds of thousands of people were demonstrating against the war across the country; 12,000 people were arrested in the Washington, D.C., May Day Protest; Army Lt. William Calley was found guilty of 22 murders in the My Lai Massacre; and The New York Times began publishing the Pentagon Papers.

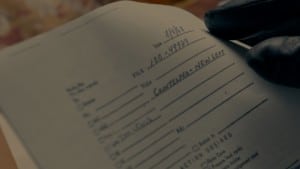

The Citizens’ Commission appeared out of nowhere to heist the FBI files, anonymously sent what they deemed newsworthy to five people — two members of Congress and three journalists — and then disappeared. What they uncovered was what they were looking for: evidence that the FBI had for several years been conducting illegal massive surveillance and using informants and agents provocateurs to degrade and destroy not only the anti-war movement, but the civil rights, Black Power and other radical or countercultural movements it considered “politically pernicious.”

This hitherto-secret program was called COINTELPRO, operational under the aegis of FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover since 1956. These revelations, along with subsequent reports on similarly unlawful activities engaged in by the CIA and the NSA, eventually led to the first congressional investigation of U.S. intelligence agencies, the Senate Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities, otherwise known as the Church Committee.

Hamilton, an experienced journalist and documentary producer, first heard about the break-in from Betty Medsger, The Washington Post reporter who received the files, and the only one of the five recipients who did not return them to the FBI. She broke the story of the content of the files in the Post, and, having discovered the identities of two of the burglars years later, was writing a book about the events surrounding the break-in.

Hamilton, intrigued by the story as a model of history — once documented on typewriters, and now in digital files, repeating itself in the age of WikiLeaks and Edward Snowden — decided she had an important and immediately relevant subject for her directorial debut. It had the additional cachet of a mystery unsolved, despite a massive effort by the FBI to find the culprits. And eight members of the Citizens’ Commission had agreed to come forward and tell their stories for the first time; five of them appear in the film.

Using interviews, archival photographs and footage, and re-enactments of the planning and execution of the break-in, 1971 effectively recreates the time, and what a time it was. The anti-war movement was alive and well in Philadelphia, and many of its strongest leaders were seasoned activists who’d gotten their first experience of organizing doing voting-rights work in the South during the 1960s.

With an end to the war nowhere in sight, and with dissent and its suppression becoming more violent, some felt that more than protest and civil disobedience were necessary. One of these was Bill Davidon, a physics professor at Haverford College. Inspired by the Catholic activists who took files out of a draft board office in Catonsville, Maryland, and burned them, he brought together several people he knew and trusted, and proposed that they see what they could find about efforts to crush dissent in the small FBI office in nearby Media.

Others we meet in the film are Citizens’ Committee members John and Bonnie Raines, Keith Forsyth, Bob Williamson and journalists Medsger and Carl Stern. Hamilton, together with her co-script-writer and film editor Gabriel Rhodes, tells a clear, compelling, at times riveting story. The re-enactments, always a chancy proposition, are very skillfully done and seamlessly woven into the movement of the film from the present to the past and back. Now, 44 years later, in this present time of sweeping surveillance by the U.S. government’s NSA, major disclosures by WikiLeaks and whistles blown by Edward Snowden, 1971 takes us back to the future.

The Philipstown Depot Theatre at Garrison’s Landing will show 1971 on Friday, March 6, at 7:30 p.m. Hamilton and producer Marilyn Ness will be present for a post-screening Q-and-A and a Depot Docs reception. For more information call the Depot Theatre at 845-424-3900 or go to philipstowndepottheatre.org. For tickets (recommended) go to brownpapertickets.com.