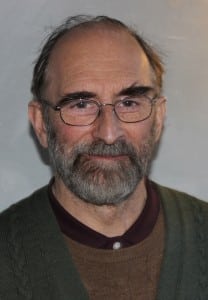

Juilliard faculty member is a Brahms scholar

By Alison Rooney

Michael Musgrave’s special guest at the two concerts he is presiding over during the Depot Theatre’s Classical Music Weekend, is, drumroll please, a piano. He’ll be “bringing” a piano “proportionate to the size of the theater” for his own concert there on Friday night, March 13, and for three piano students to perform on during the master class he’ll conduct there on Saturday afternoon.

Musgrave, according to biographical notes included in a story about him in The Juilliard Journal (he is a professor there — a specialist in German music of the 19th and early 20th centuries and the social history of British music of the same period), “started playing piano by ear at the age of 4 — from the radio, records and music in church — soon becoming fluent at playing and improvising … He earned degrees in piano at London’s Royal College of Music and organ at the Royal College of Organists, plus his bachelor’s and doctoral degrees and a certificate of music teaching from the University of London.”

After over 25 years of teaching at the University of London Goldsmiths’ College, King’s College and Royal Holloway College, Musgrave came to Juilliard, where he teaches doctoral students, in 2004. London-born and a part-time Philipstown resident, he “loves this part of the world. There are so many people interested in supporting the arts in general,” he said.

Having performed at the Depot once previously, about 10 years ago, he professed liking the theater “very much … it’s easy to talk to the audience from the stage,” something he’ll be doing a little of in between playing pieces in From Bach to Brahms, as his performance is titled, and quite a bit more of while in dialogue with the three master class students the next day.

For his own concert, he described the “connective theme” as “the use of basic ideas, variations, to create a big, extended, structure. I’ll talk a bit about the difference between piano and harpsichord, and I’ll be playing pieces I like to play and feel happy playing, and things which I hope will appeal to the audience.” He’ll be playing “works by Brahms and Schumann — not complete sets, just half, so I don’t push my luck with the audience,” he joked, “though I take it for granted that everyone loves Brahms.”

A noted Brahms scholar, Musgrave developed his interest in the composer as a child, playing the piano. This affinity continued during his later university study.

As a result of lectures at college, I came to realize that the range of Brahms’ influence was much bigger than I imagined. My first book, The Music of Brahms, tried to show his great contribution to the development of what we call classical music. People — academics — until recently still considered him a minor figure and took him for granted, didn’t realize how great the music really was. I think in the future people will realize this more and more. Every minute, around the globe, people are playing Brahms’ music, because he wrote such a large amount of music for the most popular instruments: piano, cello, violin and horns.

The master class will be structured with each of three students — Jane Cardona from Vassar, Maryna Gustavsson from Bard and Theresa Orr from SUNY New Paltz — playing one to three prepared pieces. Musgrave will respond with remarks relating to accuracy, the physical characteristics of the playing itself and interpretation.

“One must be careful not to contradict the student’s own teacher,” he said. “I focus on the origin of the text and the interpretation in the context of the first performance of it. Most of all, we’ll look at how to communicate with the audience. There’ll never be a shortage of wonderful young performers because music grabs you at a young age. But it’s no good having wonderful players unless you have an educated audience. That audience is crucial to the future of performance and composition, otherwise we just ‘listen’ [i.e., not attend and listen] to performance. If you live in Manhattan or London you’re spoiled, with so much to go to, but if you don’t, the chances of serious musical inclination are much less these days.”

The notion that classical music is for the elite rankles Musgrave, who stated: “So many great composers started out in modest circumstances. The idea that the beautiful things they offer is regarded as privileged is fundamentally wrong. Conservatories have to produce students who have to create audiences for their talent. In master classes, we then work together, collaboratively, to mature their performances.”

The program

- J.S. Bach: Italian Concerto

- Domenico Scarlatti: Six Sonatas

- Robert Schumann: Fantasy Pieces, op.12, nos. 1–4

- Johannes Brahms: Piano Pieces, op. 76, nos. 1–4; Waltzes, op. 39 (selection); Rhapsody in E flat, op. 119, no. 4