By Pamela Doan

To people who don’t know a lot about plants, I seem to know a lot about plants. I have big holes in my self-sought education, however, and identifying plants is one such area. I just want someone to tell me. That’s my preferred method. But there’s not always someone around who knows.

My phone apps fail me. Mugwort is not cannabis, iPhone. I take cuttings and use reference guides. I’ve taken an online course that was challenging because it was online and I went to college initially before the internet was a thing. I’ve read Botany for Gardeners yet still must ponder opposite, basal and alternate-leaf patterns.

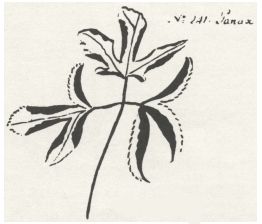

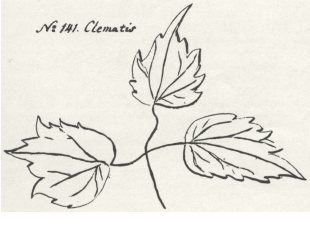

I was inspired by a visit to Boscobel to try drawing. When I stopped by to talk with Executive Director Jennifer Carlquist about their revisions of the rose garden, she mentioned they had used the plant lists of Jane Colden as reference. Colden (1722-1766), known as America’s first female botanist, carefully illustrated a catalogue of plants on her family’s 3,000-acre estate near Newburgh during an exciting time in botany. By the time of her death, she had completed 340 ink outlines.

The Dyckman mansion at Boscobel would have had many of the same plants Colden catalogued at its original location in Montrose. With the help of a team of researchers and consultants, Boscobel was able to work on a new landscape plan for the difficult-to-maintain and historically inaccurate rose garden. “The plans merge history, design, culture and climate,” Carlquist said. “The roses needed constant spraying and upkeep.”

Colden’s manuscript and historical documents about landscapes at other significant homes from the late 18th and early 19th century gave the team a working list of plants. While the current reinvention is temporary while fundraising and other renovations happen at Boscobel, the plantings are pollinator-friendly and more resilient to the extreme weather brought on by climate change.

In 1755, while Colden was sketching the plants on her family’s estate, she corresponded with John Bartram, a Philadelphia gardener who had created the most varied collection of North American plants of the time; Carolus Linnaeus, a Swedish botanist who created the common Linnaean system for plant taxonomy; and Johan Frederik Gronovius, a Dutch naturalist who published Flora Virginica in 1743. She exchanged seeds and cuttings for identification in the beginnings of the field of study.

In 1755, while Colden was sketching the plants on her family’s estate, she corresponded with John Bartram, a Philadelphia gardener who had created the most varied collection of North American plants of the time; Carolus Linnaeus, a Swedish botanist who created the common Linnaean system for plant taxonomy; and Johan Frederik Gronovius, a Dutch naturalist who published Flora Virginica in 1743. She exchanged seeds and cuttings for identification in the beginnings of the field of study.

It was an exciting time for plant lovers. When Linnaeus published Species Plantarum in 1753, it included more than 700 North American species and 70 that were new to science. Some were contributed by Colden.

In the Botanic Manuscript of Jane Colden 1724-1766, published by the Garden Club of Orange and Dutchess Counties, I found many of the native plants that I and many other gardeners are trying to bring back to the landscape. Some of my favorites — turtlehead (Chelone glabra), cardinal flower (Lobelia cardinalis), coneflower (Rudbeckia triloba), butterflyweed (Asclepias tuberosa) and vervain (Verbena hastate) — are carefully drawn and described.

In the Botanic Manuscript of Jane Colden 1724-1766, published by the Garden Club of Orange and Dutchess Counties, I found many of the native plants that I and many other gardeners are trying to bring back to the landscape. Some of my favorites — turtlehead (Chelone glabra), cardinal flower (Lobelia cardinalis), coneflower (Rudbeckia triloba), butterflyweed (Asclepias tuberosa) and vervain (Verbena hastate) — are carefully drawn and described.

Colden’s observations reveal both her status and connection to the plants. Her notes on snakeroot (Aristolochia serpentaria) read, “This S’eneca Snake Root is much used by some physicians in America, principally in Long Island, in the Pleurisy, especially when it inclines to Perip neumony, they give it either in powder or decoction. The usual dose of the powder is 30 grains.”

Snakeroot extract is still sold as an herbal remedy but the plant is considered to be endangered and possibly extinct in our area. It’s out of fashion for landscaping, lost to development and out-competed by invasive species. But as a host plant for the pipevine swallowtail butterfly, it’s worth planting and conserving in your yard.

Boscobel’s interim planting includes yarrow (Achillea), vervain (Verbena hastate), eveline speedwell (Veronica spicata), and summersweet (Clethra alnifolia), among others. All are easy to cultivate and maintain, will bloom during their busiest summer season, and will ease the transition for visitors who will miss the rose garden. “We want to highlight what our ancestors knew about the connection between sustainability and history,” Carlquist explained.

Boscobel’s interim planting includes yarrow (Achillea), vervain (Verbena hastate), eveline speedwell (Veronica spicata), and summersweet (Clethra alnifolia), among others. All are easy to cultivate and maintain, will bloom during their busiest summer season, and will ease the transition for visitors who will miss the rose garden. “We want to highlight what our ancestors knew about the connection between sustainability and history,” Carlquist explained.

When people were concerned about colonial tensions and raising their own food, tending roses wouldn’t have been a high priority. Again, it seems like so much has changed, but not much and listening to messages from history makes sense.