Beacon resident finds food in the wild

Rambling off a trail at University Settlement in Beacon, James O’Neill stops to examine a cluster of mushrooms growing at the base of a red oak tree.

O’Neill rattles off the fungi’s colloquial name (hen-of-the-woods), as well as how it’s known in Latin (grifola frondosa) and Japanese (maitake). He prefers the Japanese name, which translates to “dancing mushroom.”

The Beacon resident also notes its incubation period — when the fungi’s root-like mycelium produces the “fruit” we consume — which can take up to a month. But based on the heat and humidity, he’s able to pinpoint the week it should be best to pick.

“I’m not a scientist, just a fanatic,” he says, with a laugh.

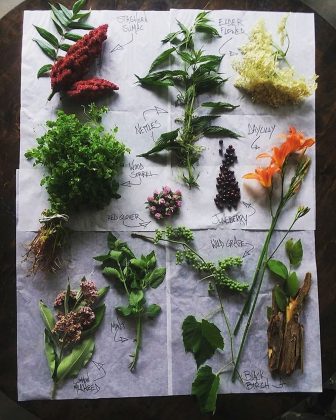

On guided, two-hour workshops, O’Neill covers the basics of foraging from both a health and legal perspective while introducing participants to the most accessible edible plants and fungi in the Highlands. He recommends that newcomers start simple: stick to legal-foraging areas, such as state and national forests (state and national parks are off-limits) or mixed-use areas. Also, look for edibles that don’t have risky lookalikes, such as hen-of-the-woods, autumn olives and garlic mustard.

O’Neill, under the name Deep Forest Wild Edibles, also sells the plants and fungi he forages to local chefs, such as Nicholas Leiss, Terrance Brennan, Brandon Collins and Michael Kelly. O’Neill’s Instagram account (@deepforestwildedible) features photos of plants and fungi he has encountered, as well as inventories of mushrooms and bags of vegetables, greens, teas and “switchels” (cocktail mixers which O’Neill prepares) that are for sale, along with recipes.

O’Neill arrived at the forest by way of the kitchen. A native of Newburgh, he spent 25 years working in restaurants before beginning to forage a decade ago. While he is self-taught, with the aid of reference guides and an indomitable curiosity, O’Neill is certified by the state to identify certain mushrooms. He also continues his education in the same autodidactic fashion, reading research papers in his spare time. (Research on the medicinal properties of mushrooms has been booming since the 1970s, he notes.)

O’Neill says he views Deep Forest Wild Edibles as a means of instilling in his neighbors a greater appreciation for the environment they cohabitate. Marketing foraged edibles to chefs gives them a story to tell about the provenance of their ingredients, bringing an awareness of the value of wild spaces that might otherwise be viewed as worthless, he says. O’Neill recently discovered a patch of groundnuts — a type of endangered wild potato — but when he returned to the site a week later, it had been razed by a Central Hudson crew installing power lines.

Even without the threat of development, foraging is a catch-as-catch-can pursuit. O’Neill notes that the spring and summer are best for vegetables, autumn for mushrooms and teas, and winters for preparing for spring. The foraging season is already fleeting, as illustrated by a cluster of chicken-of-the-woods mushrooms that O’Neill points out. While he concedes that it may still be suitable for preparing a stock, he bends a cap to demonstrate how the fungi has grown brittle.

“It’s beyond its culinary peak,” he explains. Maybe next year.