Garrison Photographer needs to raise $14,000 for special outdoor Exhibition

Garrison Photographer needs to raise $14,000 for special outdoor Exhibition

By Alison Rooney

Seeking a way to give the photographic subjects of his Newburgh portraits a chance to celebrate themselves and bask in a little rarely-given recognition, photographer Dmitri Kasterine has come up with a unique proposal: to emblazon them, in the form of 36 vinyl-surfaced weatherproof 4 ft. by 6 ft. mural-size prints mounted on the exterior of the newly-restored Ritz Theater in downtown Newburgh. The proposed exhibition would coincide with the publication of Kasterine’s book, Newburgh: Portrait of a City, which will be published in September by W. W. Norton.

The photographs will be displayed through the sponsorship of Safe Harbors of the Hudson, a nonprofit organization that is committed to transforming lives and building communities through housing and the arts in Newburgh. Organized by the Ann Street Gallery, an affiliate of Safe Harbors, the intention of this outdoor display is to allow all the citizens of Newburgh free and constant access, with a goal of “embracing the people of Newburgh.”

In today’s arts economy, with dwindling grant and large donor support, to generate funding for this project, Kasterine has turned to Kickstarter, the successful 3-year-old site which encourages small private donations to approved, finite, creative projects. Believing that “a large group of people can be a tremendous source of money and encouragement,” the Kickstarter methodology entails a submission of a project, — which Kickstarter then accepts or rejects — with a beginning and end, definable expectations, a set target amount price tag for just that project and a small “reward” for donors, who can then donate any amount of their choosing.” Each Kickstarter project has a deadline date by which all funds must be raised, and no monies are collected in advance of that ending date; if the full amount is not raised in that time, all pledged monies remain uncollected. The deadline for this project is April 11, and the target amount required is $14,000, with a budget as follows:

| Manufacture of prints and mounting Delivery Installation Design, marketing, promotion TOTAL |

$9,360 |

Revenue from the sale of prints will be given to a Newburgh charity.

Newburgh has long suffered from what seems like an irretrievable urban blight, with the usual smorgasbord of adjectives tossed about: derelict, crime-ridden, crumbling. With this exhibit, Kasterine wants to turn the focus away from those words, and instead towards the people who live there, some of whom are descended from the original Native American population and others who can trace their heritage to the great migrations north after WW II. Newburgh’s history is non-linear. Brief excerpts from A History of the City of Newburgh by May McTamaney, City Historian, tell of a land originally settled by the Waoranek, part of the Lenape tribe of the Algonquin nation, who lived in bark-covered huts, grew crops, hunted and fished along the river. Hudson’s Half Moon arrived in Newburgh Bay in 1609 and notes from the log called it “”a pleasant place to build a town.” By 1684 the English crown had replaced the Dutch West Indies Company as the colonial government, and Newburgh’s first settlers arrived in the spring of 1709. According to McTamaney’s history,

Newburgh has long suffered from what seems like an irretrievable urban blight, with the usual smorgasbord of adjectives tossed about: derelict, crime-ridden, crumbling. With this exhibit, Kasterine wants to turn the focus away from those words, and instead towards the people who live there, some of whom are descended from the original Native American population and others who can trace their heritage to the great migrations north after WW II. Newburgh’s history is non-linear. Brief excerpts from A History of the City of Newburgh by May McTamaney, City Historian, tell of a land originally settled by the Waoranek, part of the Lenape tribe of the Algonquin nation, who lived in bark-covered huts, grew crops, hunted and fished along the river. Hudson’s Half Moon arrived in Newburgh Bay in 1609 and notes from the log called it “”a pleasant place to build a town.” By 1684 the English crown had replaced the Dutch West Indies Company as the colonial government, and Newburgh’s first settlers arrived in the spring of 1709. According to McTamaney’s history,

By 1750, Newburgh had expanded to nine streets — four parallel to the river and five heading west from the shore. Mills were operating along the creeks, farms were productive, and there were two docks on the Hudson: one public, at the north end of town, the other private, at the south end, at the foot of the Hasbrouck farm. A ferry had begun carrying passengers on daily trips to the other shore, replacing the former practice of hiring a private boatman as needed. New lumber mills fed the growth of ship, home and commercial building. The great American melting pot began to simmer, as German Palatines were joined by Dutch, English, Scots and a few Africans working as free, indentured or slave hands on the larger farms in the area.

During the Revolutionary War, hundreds of troops encamped in the area, and George Washington guided the war from his headquarters there. It was in Newburgh that peace was declared and its terms decided. From that point Newburgh became a major commercial center, an easy base for sailing sloops and steamboats. Manufacturing began, banks were established, and impressive homes were built. The prosperity continued through the Civil War period and beyond, with many Victorian residential and commercial buildings constructed.

The economic vitality continued as this excerpt from the history describes:

As the 20th century dawned, Newburgh was thriving, with over 100 manufacturing plants. Newburgh industries were predominantly machine shops, shipbuilding yards, cloth manufactories, clothing design and production factories, brickyards, plaster works and shipping concerns. Newburgh was a major center for retail shopping for the entire Hudson Valley up through World War II. Many old-timers still recall the awesome array of shops lining Broadway, Colden and Water streets. Newburgh was also a recreational hub. Sports included speed skating, ice boating, yachting and rowing clubs, baseball leagues, casinos and dance ballrooms, as well as many picnic groves, amusement parks and river excursion steamers.

As World War II ended, there was another building boom – the city’s largest population of 32,000 was recorded in the 1950 census. But the same growth that blessed Newburgh started to curse it as well. All those transportation routes turned the open countryside into suburbs, and America fell in love with its cars. Shopping centers attracted more customers than the Water Street business district. Interstate trucking routes made the movement of goods across great distances cheaper, and manufacturing followed cheaper utilities and lower-cost labor in the South. The growth of chain stores made it too costly for family businesses to compete: many folded by 1970. The air force base at Stewart Field closed in the early 1970s, emptying many city apartments and taking away the customer base of many local businesses.

The 1963 opening of the Newburgh-Beacon Bridge, which bypassed the waterfront and city center, drew more visitors away, and suburban shopping malls opened up, to the detriment of the establishments in the city center. On top of all of this urban renewal projects pulled down historic structures in the city center with never-realized intentions to build anew, residents were relocated to housing projects and the city deteriorated rapidly. Today, per the 2010 census, with a population of 28,866, 47.9 percent Hispanic/Latino and 30.2 percent Black/African-American, the median household income is $36,153, with many living below the poverty line.

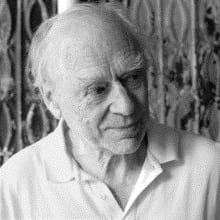

All of this historical background is both pivotal and unimportant to Dmitri Kasterine. Pivotal in the shaping of his subjects’ lives but unimportant in the sense that these lives go beyond just their circumstances. Long a photographer of renowned figures in the literary and art worlds, Kasterine, originally from England, spent the 1970s and 1980s taking commissioned portraits for top magazines, including Harpers & Queen, Vanity Fair and Vogue. A 2010 solo exhibition of his work at London’s National Portrait Gallery consisted of studies of writers, filmmakers and artists, including Samuel Beckett, Martin and Kingsley Amis, Robert Graves, Stanley Kubrick, Francis Bacon and David Hockney. In 1986, following a commercial assignment photographing Mick Jagger in Los Angeles, he visited New York City, where “I had a lot of fun and thought ‘I’m not going home.’” He moved to New York, living first in the city in a Soho loft, producing work frequently for corporate magazines (“a good racket, then!”), and later, following a visit to the Hudson Highlands to see a friend, in Garrison, where he has lived ever since.

His own description of his beginnings in his field,

Photography came to me at age 11, photographing birds at the bird feeder my mother put up outside the kitchen window. After the acute disappointment of the birds being minute specs in the picture, I did cows in the fields around us in Kent. … After the wine trade, Lloyd’s, racing cars, selling cars and flying airplanes to Australia, I became a photographer. I photographed my friend’s engagements and their weddings. I worked for magazines and advertising agencies.

Along with his commercial work, Kasterine has also focused on personal photographic essays; his earlier subjects included England and the English and portraits of Brooklyn residents. Newburgh beckoned when “I abandoned photographing people around here, because they looked like the people I left behind in England. Someone said ‘Why don’t you go to Newburgh?’ Off I went, on a boiling hot day, and I was immediately struck by the beauty of the place, the buildings, the people. … Photographing them appealed to me enormously. I’m not a social issues or political photographer, although after a while I got drawn into it, of course, as I found out more of how much Newburgh is a victim of the disaster of urban renewal where now you have three or four generations of people who have never been able to find work. It was torn down with alacrity, never built up again. People have been left with nothing. It’s not unique, look at Buffalo, Athens. … The city doesn’t know what to do with all the vacant buildings.”

Along with his commercial work, Kasterine has also focused on personal photographic essays; his earlier subjects included England and the English and portraits of Brooklyn residents. Newburgh beckoned when “I abandoned photographing people around here, because they looked like the people I left behind in England. Someone said ‘Why don’t you go to Newburgh?’ Off I went, on a boiling hot day, and I was immediately struck by the beauty of the place, the buildings, the people. … Photographing them appealed to me enormously. I’m not a social issues or political photographer, although after a while I got drawn into it, of course, as I found out more of how much Newburgh is a victim of the disaster of urban renewal where now you have three or four generations of people who have never been able to find work. It was torn down with alacrity, never built up again. People have been left with nothing. It’s not unique, look at Buffalo, Athens. … The city doesn’t know what to do with all the vacant buildings.”

During 15 years of photographing in Newburgh, Kasterine has a simple method of finding subjects: he walks right up to them, telling them of his plans for a book, and offering to give them a print. “Most people say yes, and have been very pleased with the images. I have the advantage of being too old to be a policeman! I speak funny [Kasterine has retained his British accent], and have a natural tendency to be very polite — I’ve never been caught taking a ‘stolen shot.’ Some people are a little suspicious of me, but most have been friendly and enjoyed the attention.” Now, many people know him, “Recently people have come up and told me ‘you took my picture 15 years ago.’ It’s a thrill that they remember.” Kasterine has re-photographed some of his subjects from the early years, as well as structures, “houses which have changed because they’ve collapsed further.”

During 15 years of photographing in Newburgh, Kasterine has a simple method of finding subjects: he walks right up to them, telling them of his plans for a book, and offering to give them a print. “Most people say yes, and have been very pleased with the images. I have the advantage of being too old to be a policeman! I speak funny [Kasterine has retained his British accent], and have a natural tendency to be very polite — I’ve never been caught taking a ‘stolen shot.’ Some people are a little suspicious of me, but most have been friendly and enjoyed the attention.” Now, many people know him, “Recently people have come up and told me ‘you took my picture 15 years ago.’ It’s a thrill that they remember.” Kasterine has re-photographed some of his subjects from the early years, as well as structures, “houses which have changed because they’ve collapsed further.”

The idea for an outdoor exhibition of the prints came about when Kasterine and his wife Caroline were wandering around Newburgh, looking at abandoned buildings where they might install the exhibition. “I suddenly thought, why not outside?” Through a realtor they made contact with Safe Harbor’s founder and director Tricia Haggerty Wenz, who suggested her organizations Ritz Theater. The prints will remain protected from the outdoor elements through the use of an alumcore 5mm-thick vinyl surface sandwiched with aluminum backing, foamcore in between.

The idea for an outdoor exhibition of the prints came about when Kasterine and his wife Caroline were wandering around Newburgh, looking at abandoned buildings where they might install the exhibition. “I suddenly thought, why not outside?” Through a realtor they made contact with Safe Harbor’s founder and director Tricia Haggerty Wenz, who suggested her organizations Ritz Theater. The prints will remain protected from the outdoor elements through the use of an alumcore 5mm-thick vinyl surface sandwiched with aluminum backing, foamcore in between.

With no funding looming other than this Kickstarter drive, Kasterine is hoping that the details found on his Kickstarter page, and, more fully on his blog, which includes not just the images, but also descriptions of his subjects, along with an increasing number of video portraits of them, stimulates those moved by the visuals and the stories behind them, to contribute whatever amount they are able, and collectively back the exhibition.

Photos courtesy of Dmitri Kasterine

Lovely story, beuatiful photographs and faces, great project to support.

Thank you Alison for this thoughtful report. Very informative in so many ways.