Labor built an industry and community

By Liz Schevtchuk Armstrong

On Thursday, Aug. 18, 1859, William Penman, a 19-year-old apprentice, went to his job at the West Point Foundry. He never came home. In an incident shrouded in mystery, he died on the job, “killed by a cannon discharge,” according to a sketchy note in an obscure book.

Whether any parents or siblings mourned him is unknown, but his young peers clearly felt his loss. His tombstone, in the Old Cold Spring Cemetery (next to the Haldane school campus), was “erected as a tribute by fellow apprentices,” relates the obscure source, Old Tombstones of Putnam County, a 1975 compendium of grave listings. Though visible 40 years ago, Penman’s tombstone, if it still exists, today cannot readily be found; graveyard weeds grow high, many stones lie toppled, and inscriptions on others have worn away.

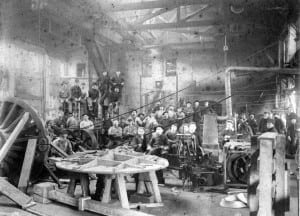

A diverse workforce — except in gender

Penman’s untimely demise, portending the deaths of thousands of young men a few years later in the Civil War, underscores the risks confronted daily by those who turned Cold Spring from a tiny riverfront hamlet into a thriving 19th-century village, home to an innovative industrial giant, the West Point Foundry, an ironworks established in 1817. Known not only for its state-of-the-art cannons, but for policies both enlightened and paternal toward workers, the foundry offered employees houses (initially rented, then sold), many still in use, and encouraged family life.

The men — so far, research reveals only one woman in the workforce — settled into new village neighborhoods; their children went to a foundry-built school (where apprentices likewise took classes) and they socialized and worshipped at WPF-supported churches. They worked in the foundry machine, pattern, blacksmith, and casting shops; and in the boring mill, offices, and other facilities.

For a time, the foundry included a large smelting furnace and kept sloops to transport goods on the Hudson River, crucial before the railroad arrived. WPF employees produced train and steamboat components, water pipes, building facades, agricultural equipment, household implements, stoves, and more, in addition to cannons and armaments.

Sometimes specifically recruited (especially at the beginning), they traced their origins to Ireland, England, Scotland, France, Germany, and Puerto Rico, as well as New York state. Collectively, they filled laboring, trained crafts, and managerial positions. Archaeological digs at the location of homes built within the foundry boundaries found scientific instruments, quality ceramics and porcelain, toys, and similar items, evidence of comfortable middle-class lives.

Thanks largely to the foundry and its employees, by 1852 Cold Spring sported what one news story described as *neat and tasty buildings, with comfortable homes and happy firesides.* Even so, accommodations were not always so attractive: during the Civil War, when an expanded workforce flooded the village, the foundry brought in a barge on the Hudson to serve as staff dormitories.

Over the years, through their patronage, WPF personnel also helped fuel the growth of Main Street’s numerous shops, professional offices and businesses, listed abundantly on 1860s maps.

“The workers provided the skills that made the West Point Foundry a success and, in turn, contributed so much to the development of the village,” said Rita Shaheen, Scenic Hudson parks director, Aug. 26. “Through their work in manufacturing Parrott guns, they also played a critical, if unheralded, role in winning the Civil War.”

(In 1996, decades after the foundry closed, Scenic Hudson, a regional environmental organization, bought the property and later converted it to a historical park.)

But trainees like Penman were tightly controlled — apprenticeship rules forbade sex, card games, and hanging out at bars, among other taboos. The older, regular workers often endured 10- or 12-hour shifts in the sprawling foundry, which stretched from approximately Chestnut Street to the Hudson River. Over everyone loomed the potential for disasters like the one that killed Penman.

Perils in proofs

Tests or proofs of cannon, to ensure proper functioning, could be particularly hazardous. “Things like that” — fatal accidents — “in a proofing exercise sound all too common,” Steven Walton, an assistant professor at Michigan Technical University, told The Paper, Tuesday (Aug. 26). In Penman’s case, Walton suggested, “it could have been an accident or could have been a bad barrel that blew up. Typically the company proofed it once or twice themselves, and then if it did not blow, they subjected it to an Army or Navy proof again. So if he was killed in that, I would bet it would have been an accident in the company’s proof process.”

Walton worked on the WPF archaeological dig and has researched and written about foundry topics. Michigan Tech, a leader in industrial archaeology, conducted excavations at the WPF from 2002 to 2008.

“Accidents came with industry, and they happened regularly at the foundry, where workers contended with deafening sound, flying sparks, molten metal, and tools and products that weighed in the tons,” the Scenic Hudson mobile WPF tour explains. “Add to that the crowded, cramped workspaces and stress of ever-increasing production demands during the Civil War, and the foundry’s doctor would have been just as busy as the rest of the workforce.”

The long-time WPF physician, Dr. Frederick Lente, in 1853-54 built The Grove, a spacious but now derelict home above Chestnut Street, and became nationally renowned for his medical acumen.

Two serious foundry mishaps preceded an 1864 worker strike, a job-action ostensibly sparked by dissatisfaction over wages but launched at a time when the foundry ran 24 hours a day, under intense pressure to produce war materiel. Involving attempts to lift heavy weights, the accidents left one man with a broken leg and the other with a broken collarbone, according to Scenic Hudson.

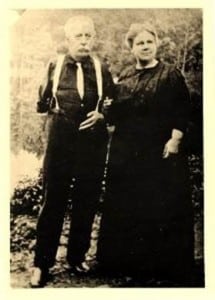

Also at some point, WPF worker James Lahey lost part of an arm in an on-the-job accident. He survived, to pose with his wife, Margaret, in a photo — now included in Scenic Hudson’s mobile tour of the site.

The WPF paid financial assistance to injured workers who could no longer function on the job.

Foundry executives also put in long stints. Letters from Foundry Superintendent Robert Parrott, an inventor and former Army officer who created the highly successful cannon that bears his name, attest to his inability in 1863 to even cross the river to visit the iron furnaces that provided the foundry with metal. Cannons “are ordered by the fifties” by the Union “and all my efforts required to keep up the supply,” he wrote to his brother. “I have no let-up in the calls for guns” and ammunition, he reiterated several weeks later, “in fact, it is increasing daily.” (The West Point Foundry and the Parrot Gun, a booklet by Charles Isleib and Jack Chard, contains excerpts of the correspondence.) During the war, the foundry employed more than 1,200 workers, about 2.5 times its pre-1861 level.

A war-time walk-out

Notwithstanding Parrott’s 24/7 duties, the nitty-gritty, hot, physically demanding labor fell to the factory workers. The strain perhaps contributed to the sole serious (or publicized) WPF strike, in March 1864, when, according to The New York Times, about 300 workers, forming the Laboring Men’s Union, walked off the job on a Thursday, forcing others to leave as well — abruptly shutting the plant.

The diplomacy of Father J. Caro, the local Catholic priest, who convened a worker meeting; a cordial greeting from Parrott’s wife when the workers marched en masse to the couple’s home, accompanied by Caro; the fact Parrott himself stayed at work, shrugging off any threats; private negotiations; and the arrival of 120 soldiers, joined by the Putnam County sheriff, to arrest the alleged strike leaders and ensure production resumed, all seemed to end the walk-out without violence. For a while, however, tension prevailed and teachers at the foundry school fled Cold Spring, worried about attacks.

“Groups of men in earnest conversation may be seen on the corners of the streets and in the grog-shops of this usually quiet village. The work at the foundry is still stopped and fear is entertained lest injury to life and property may ensue,” a New York Times article reported, two days after the strike began. “It is to be hoped this unfortunate affair may soon be brought to a favorable termination and that the West Point Foundry may speedily resume its operations, for its importance in connection with the government and the war is incalculable.”

A day later, the Times reported that the strike was largely over, with work beginning to resume, though a military guard remained. “The property and persons of the [village] inhabitants have not been injured and under the circumstances the [striking] operatives have conducted themselves with greater decorum than was expected,” the correspondent wrote.

An end in 1911

After the war, business slacked off and in 1873, during a U.S. economic downturn, the foundry cut back workers to 75 percent of their normal hours. The factory continued for another 38 years, but steel replaced iron and the heyday of the 1820s-60s never returned. Though the J.B. & J.M. Cornell Co., a New York City business, acquired the foundry in 1898 and oversaw upgrades and expansions, the foundry closed in 1911.

Nonetheless, despite the ups-and-downs of its latter years, the workers still felt enthused enough to maintain a WPF band and play on a baseball team.

For more on the foundry, visit the Putnam History Museum, with its foundry-related collection, 63 Chestnut St., Cold Spring; consult West Point Foundry, by Trudie A. Grace and Mark Forlow, an Arcadia Publishing 2014 book; tour the West Point Foundry Preserve and take advantage of the mobile tour, also found on the Scenic Hudson website.

Parrot rifles still exploded when in actual use. This article describes one such explosion in Charleston and another at Fort Fisher, N.C. I read somewhere and some time ago that this was one reason there was not a lot of demand for the guns after the war.

A few years ago (20-25?) fires broke out on the west side of the river all along the mountains. You could see the flames raging as you headed north from Peekskill on the train ride home. West Point helicopters scooped up huge buckets of water from the river to help douse the fire. It burned for several days apparently exploding live ordinance the Foundry had shot over to Crow’s Nest a hundred years ago testing its rifles. The forests were closed for some time afterwards to search for any other unexploded ordnance.

Thanks for this…. I loved reading about my former backyard.