Chuck Thomas can tell you, with a few taps of his phone, that the tree we’re sitting under at Tyrone Crabb Memorial Park in Newburgh is a littleleaf linden.

Nothing unusual there. Many smartphone apps such as iNaturalist can identify flora and fauna. But with a few more taps, Thomas can tell you that the littleleaf linden is sequestering over 24 pounds of greenhouse gases every year and retaining 114 gallons of water.

On a sweltering day like today, the 5.72 kilowatt-hours in energy savings can also be felt to those of us sitting under the tree’s shade. “Seven degrees cooler here than over there,” says Thomas, pointing to the broiling, tree-less section of South Street.

All in all, this little tree is saving the city of Newburgh $47.38 a year in “eco benefits,” according to a map at newburghny.treekeepersoftware.com created by the Davey Resource Group as part of a joint project with the Greater Newburgh Parks Conservancy, Outdoor Promise and the Newburgh Conservation Advisory Council, which Thomas chairs.

The groups are working together to replace the 4,000 street trees that Newburgh has lost over the years to neglect, disease or being improperly planted. At the same time, it hopes to protect 3,757 other trees that are saving city residents an estimated $482,000 in energy costs.

“We used to be a well-canopied city,” says Kathy Lawrence of the Greater Newburgh Parks Conservancy. “Now we’re not.”

She pointed out that as the planet continues to warm due to climate change, green infrastructure such as trees and parks have become vital components for the future of cities because of the way they cool the air temperature, fight pollution and prevent flooding.

“People don’t get that,” Lawrence says. “We’re using the inventory to say: ‘This is the economic benefit, this is the public health benefit, this is the cooling benefit.’ ”

Still, for all the quantifiable benefits of trees, Thomas is drawn to their ineffable qualities. “What a difference!” he says after we leave the park and journey from a block without trees to one with an established canopy. “It just doesn’t have that hardscrabble look to it.”

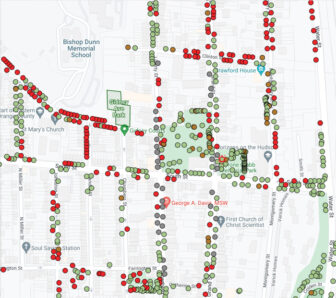

In addition to pointing out where Newburgh’s trees are, the map notes where trees used to be. “I love that missing trees are marked in red,” says Lawrence. “That’s heat.”

The streets lined with red dots also indicate where replanting efforts should be focused, she says. Outdoor Promise went from door to door in those neighborhoods to ask residents if they would be willing to help care for trees, as plantings require up to 40 gallons of water a week from May through October. Not everyone was willing: Some residents worried about branches falling on their cars, or if they would be responsible if the trees’ roots broke up the sidewalks.

“Some landlords don’t want trees because they want to keep things looking scrappy,” Thomas says. “I’ll leave it at that.”

Residents who had been interested in planting street trees on their own ended up discouraged. “It says in the code that you have to get a permit,” says Lawrence. “If you ask for a permit to plant a tree, you’re handed a 13-page building permit that mentions trees exactly zero times.”

The city hadn’t had much luck on its own, either; it would sometimes plant trees on streets with power lines, only to have to cut the trees down as they grew. A few years ago, the city planted ash trees along Water Street, not realizing that they would soon be felled by the invasive emerald ash borer.

Through a series of grants and funding from the city, the three nonprofit groups are working to plant 40 trees a year, spread out among Newburgh’s four wards. After compiling a list of hardy trees that won’t get destroyed by disease or grow too tall, they’re identifying where exactly they should go.

On a block of Upper Broadway lined with red dots on the map, Thomas points out the empty planters at the curb where trees used to be. One of them sits in front of Rhinebeck Bank, the only bank left in the city. Thomas has convinced the bank manager to water the forthcoming tree every day, even if it involves making several trips back and forth from the bathroom sink with a bucket. He points to a banner in front of the bank that says “Rhinebeck Bank Believes in Newburgh.” “We’re holding them to that,” he says with a laugh.

In the end, the map may help to grow more than trees. “Grow a tree, grow a community” to care for them, says Thomas, as he waves to someone on the other side of the street. “When I moved here, I didn’t know my neighbors. And now, last year, that guy got married in my living room.”

As I scan our “local” daily (nowadays not-so-local) paper, it is becoming more and more rare to find a story about the Hudson Valley’s biggest, most diverse and most vibrant city — Newburgh. Today I was delighted to see in The Current your terrific story by Brian PJ Cronin about Newburgh’s successful ongoing efforts to re-green the city, and about how trees are helping us physically, socially, financially and psychologically. A big thank you to Mr. Cronin, and to The Current.