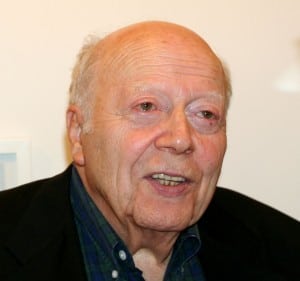

Philipstown’s Henry Stern: “This gave me hope because they are … not hiding from the story …”

By Alison Rooney

Henry Stern, a Philipstown resident and member of the Philipstown Reform Synagogue, spoke May 4, at the Marina Gallery. He talked about his experiences returning to the town in Germany where he lived until age 11, when he left, just one week before war was officially declared.

Stern was invited back to Germany by the Jewish Culture Museum Augsburg-Swabia, as the culmination of a project which included the assembling of a comprehensive 104-page book about his family, workshops, talks and other activities designed primarily to educate young Germans in a non-academic, personalized way, about that devastating period in their country’s history.

Stern shared his experiences, sprinkling his talk about this project, called Lifelines, with details from his life in Germany before the war, and his experiences upon leaving Germany for England, and then the United States, in 1939. The talk was presented in honor of Yom HaShoah, Holocaust Remembrance Day, which began at sundown April 27, and continued through April 28 this year.

Excerpts from his talk follow:

“We were invited to my home town, Augsburg, an old Roman Town — from Augustus — near Munich, part of Bavaria. It’s about the third largest city in Bavaria. Jews settled there back in the Roman days; they were tradespeople. My family for a long time had to live in surrounding areas, not in town, where they weren’t allowed until the time of Napoleon. I love the town and had many feelings going back again. I had been back once before, in 1996, [that time] invited by the town. I was a showpiece — interviewed, with questions like ‘How do you feel now?’ etc.

“This Lifelines project was developed by the museum, which is connected with the synagogue there. The people who are doing it are very dedicated individuals, and not one of them is Jewish, in fact the head of the museum is not Jewish. When the war was over, only 25 Jews came back to the town, from the camps. They decided they had to have some communication with others and not just be an enclave. In 1935/36 Augsburg’s Jewish population was about 1,400; by 1939 it was down to 1,200, of whom about half escaped and half died.

“Today the population is around 1,600, and 90 percent of the current population are Russians, who came in as displaced persons. Some returned from Israel. They decided they had to do something because they [some of the Russians and also the non-Jewish population] don’t know anything about Judaism. The museum has a lot of treasures, things from other synagogues, like shields and Torah covers and they found they had to educate the young. Today it’s a thriving community.

Preserving a personal history

“They came up with the idea for these books. The funding came from a wealthy paper mill owner. His mother was a Nazi; his father was disillusioned. He decided to fund it because he wanted to make sure the younger generation would never experience this. Mine is the sixth book in the series. The program required me to get data and photographs, and they asked me a million questions, through the Internet. Through Desmond-Fish Library equipment I was able to transmit hi-res images. There were other phases in the program. I had to develop and write up all the different occurrences in my life, including getting out of Germany and my new beginning in Washington Heights. I had to learn German again — mine wasn’t that good.

“The first part of the program there was a theater performance, reading parts of my story while a musician played; doing a PowerPoint. My brother was in a kindertransport and kept a journal. They read some of it aloud. There was also an exhibit, which included things like my German passport which has a large red J for Jewish on it. There were lots of non-Jewish attendees, and there was a Q-and-A at the end.

“Then there were four days of workshops attended by students from four different high schools. The students had hands-on activities to do, for example one compared a particular date and asked them to research what their families did during that period as compared to ‘What happened to Henry then?’ The Germans asked a lot of questions. They asked me things like ‘What were the first signs of anti-Semitism?’ I was surprised at how much the students knew. They had been on a trip to Dachau. They told me that things have changed a lot and that now there is much more information available to them on the Holocaust, whereas it used to be just a paragraph in a textbook.

“The students themselves had changed a great deal since my 1996 visit, now they include many Turks, Russians and Syrians. One of the questions I was asked was what did I put into my suitcase when I left? — did I bring a teddy bear? At the end of the session they gave me a teddy. I showed them many of my actual documents. They were thankful to have someone as an eyewitness.” All the workshops were filmed, and turned into CDs and DVDs for future generations to access.

Stern spoke more directly of his family’s experience prior to and during wartime. He described two cousins, Trude and Margot, whom he was close to, mentioning that as anti-Semitism spread, friends were lost and thus families became even closer. The girls were supposed to have joined Stern’s older brother as part of the 10,000 children put on trains to England, escaping Germany. As Stern later noted, 90 percent of these children never saw their parents again, Stern’s brother Fred being an exception.

Stern’s mother sent his brother on the train, but couldn’t bring herself to send both boys — “my mother held on to me,” Stern remembered. Part of the rationale for this is that she knew their family was due to go to England a week later, as they had sponsors in place. Sponsors provided money — in Stern’s family’s case this came from an uncle living in the United States. Jews were permitted to take a maximum of $10 per person out of Germany when departing. The sponsor money arrived just four days before the war broke out.

The girls didn’t want to go on the train either and said, “Henry isn’t going, why should we?” The girls never made it out.

“They ended up on a transport to Poland and never made it off the train; they perished,” Stern recalled, something which has always struck deeply within him ever since. On a visit to Augsberg City Hall this time, Stern saw a memorial to the Jews from the town of those who were killed, and noted his cousins’ names.

Stern concluded his talk speaking of his last evening in Augsberg and travels beyond it.

“The last night of my stay was the 75th anniversary of Kristallnacht and there were about 3,000 people in the synagogue. A student orchestra was playing Kaddish music; they were from the same school which threw my two cousins out. After that we decided to go to Berlin where we visited the Holocaust Memorial, which is 2,711 slabs of stone, varying in height, with no inscription, near the Brandenberg Gate. The sun was setting, it was dark, and we couldn’t find the underground entrance. Finally we saw a group of young people standing in line, waiting to get in. This gave me hope because they are indoctrinating and teaching and not hiding from the story of the Holocaust.”

With that Stern read a poem written by his brother in memory of Margot and Trude, bringing his talk to a moving conclusion.

Photos by Stephanie Rudolph