For a century, through prosperity and challenge, boom times and bust, Beacon has maintained its identity and its place in the cultural and historic pantheon of Hudson Valley communities. For its survival, it has adapted to an ever-changing demographic and an often devastating economy. And on May 15, a Beacon that has virtually risen from the ashes will celebrate its hundredth birthday.

A tale of two Beacons

Actually, 101 years ago, there were two “Beacons.” One, called Matteawan, was a thriving industrial center, while the other — Fishkill Landing — operated as a bustling river port town. The land on which they sat, which one of Henry Hudson’s crewmen described in 1609 as “pleasant a land as one need tread on,” had been occupied by white settlers since the late 17th century.

The royal governor had purchased an 85,000-acre patent from the Wappinger American Indians in 1683 and granted it in part to Francis Rombout. At Rombout’s death, one third of the property passed to his daughter, Catheryna, who homesteaded the land with her husband, Roger Brett.

When Brett died in 1726, his widow remained on the estate, selling off enough land to ensure the permanent white occupation of the area. She was the matriarch of a seven-generation dynasty, and her house still stands at 50 Van Nydeck Ave. as a Beacon landmark, the Madame Brett Homestead.

Throughout the 1800s, the two communities coexisted beside one another, each prospering in its own right. Matteawan owed its existence to the Industrial Revolution. It utilized the force of Fishkill Creek to power its many mills and factories, enriching its businessmen and providing work for its labor force.

For its part, Fishkill Landing took full advantage of the Hudson River for its commercial well-being, its dockage accommodating vessels that ranged from the simplest Hudson River sloop to the largest steamboats on the water.

Inevitably, the two communities expanded, growing ever closer to one another, until they shared a Main Street. Discussions proposing the combination of the two communities into a single entity were conducted as early as 1864 — the year Fishkill Landing was incorporated as a village — but no action was taken for several decades.

In 1910, the state Assembly and Senate approved a bill for the charter combining the two villages into a single city, but Gov. Charles Evans Hughes vetoed it, as did his successor, Gov. John A. Dix.

It was not until May 15, 1913, that the bill was signed — by yet another governor, William Sulzer — and the city of Beacon was born. The name (originally proposed as “Melzingah,” after a local tribe) was chosen to commemorate the signal fires set upon the mountaintop during the Revolution, to warn Gen. Washington’s troops of a British advance.

The thriving city

For decades, the city thrived, from the combined demand on its factories and businesses, and the commercial viability of the Hudson River. President of the Beacon Historical Society Robert Murphy proudly points to the city’s “firsts” during this period: the first file manufacturing plant in the country, the nation’s first lawnmower factory (at the site of the currently restored Roundhouse), the first trolley car system in the Hudson Valley. Not all of Beacon’s attractions were commercial.

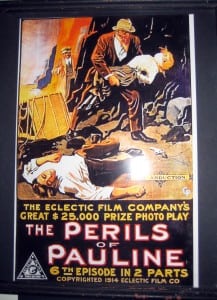

The Mount Beacon Incline Railway, the city’s greatest claim to fame, was built in 1902 at the staggering cost of $165,000 and was originally serviced by the railroad, steamboats, the Newburgh-Beacon ferry and the local streetcar system. During the silent film era, famed director D.W. Griffith shot three features on the mountain, using the railway — and a small herd of pack animals — to carry crews and equipment to the summit.

The Incline Railway functioned well into the 1970s, attracting tourists from all over the world. As many as 110,000 visitors in a season came to marvel at the views, vacation in the hotel and cottages, and dance and dine in the casino atop the mountain.

Beacon has always been a working-class town. From its earliest days, the residents relied on the mills and factories for their pay, and on the stores, shops and services within the community itself for all their needs. In turn, their patronage fed and maintained these businesses. In the first half of the 20th century, Beacon was a thriving commercial hub. It supported three department stores: Grant’s, Schoonmaker’s, and Fishman’s.

The Nabisco boxing plant, built in the 1920s, provided work for many of the locals, as did a number of other plants and factories. The city’s New York Rubber Co. made the country’s first rubber toys and balls and supplied such products as industrial belting in peacetime and life rafts during the Second World War.

According to a local legend, when a young WWII fighter pilot named George H.W. Bush was shot down over the ocean, it was a Beacon-made life raft that saved his life. In fact, he might well have been wearing a flight jacket manufactured by Beacon’s Aero Leather Company.

Financial setbacks

The Depression hit Beacon hard, but the city soon regained its momentum. During the late-1930s and into the ’40s, businesses were back on track. The construction industry thrived, as houses and commercial buildings continued to go up, built by such well-known local contractors as James “Jimmy” Lynch.

As Murphy put it: “Everything was peachy. The residents didn’t even need cars; they could walk to work and shopping. Beacon was a self-contained city.”

The 1960s saw Beacon suffering the same game-changing setbacks that were afflicting small cities and towns across the nation. The river had long since ceased to provide the arterial flow of commerce to the Hudson Valley. And with the advent of the new malls, the centrist orientation of the community dissolved, as shopping and entertainment patterns shifted beyond the city limits.

Cheaper goods in a wider variety became available in the chain stores, local shops were forced to close, and the old, one-show movie theaters were replaced by glitzier, multi-feature meccas located just outside of town. One by one, over the next 30 years, Beacon’s once-sustaining businesses disappeared. Nowhere was this decline more pronounced than at the east end of Main Street.

(Photo by Kate Vikstrom)

Murphy recalled a depressing series of events: “We lost our two theaters in the late-’60s. Within a short time, the workers at one of our big factories struck, and the owners found cheaper labor in North Carolina. Then, when New York Rubber struck, the plant simply closed.

The Braendly Dye Works shut down around 1980, and Green Fuel Economizer, which had employed some 400 locals, soon followed suit. By 1991, we had lost our daily paper and our hospital. And when Dorel’s Hat Factory finally shut down in the mid-’90s, it marked the end of Beacon’s long run as one of the nation’s premier hat-making centers.

“Most important,” said Murphy, “we were losing our personality, and our identity.”

Revitalization

In the late 1980s, by which time many of Main Street’s buildings were boarded up, a white knight appeared in the form of contractor and entrepreneur Ron Sauers. Where buildings were nothing more than burnt-out shells, Sauers and his wife, Ronnie, saw historically restored storefronts and apartments. And where rows of commercial buildings stood untended and ignored, they envisioned — and, with the enthusiastic support of the local government, initiated — the renaissance of the City of Beacon.

Over a 25-year period, they resuscitated the east end and were well on their way to gentrifying the other end of Main Street. Said Murphy, “Ron Sauers was the father of Beacon’s revival.”

Another massive boost was given Beacon when the Tallix Art Foundry and the Dia Art Foundation elected to make the city their home. This started a rush of developers, and the revitalization of Beacon continued apace.

Then, in 1993, a major Hollywood production company chose the city as the setting for its mega-star vehicle Nobody’s Fool. Beacon was definitely on its way to a recovery that is reflected today in its fine shops, art galleries and restaurants, and by the visitors who travel distances to spend a day or a weekend.

Murphy, in describing the qualities that made — and make — the area unique, waxed rhapsodic: “With its mountain, river and creek, Beacon was blessed by geography. Our mountain was used for recreation, and our creek as a power source, while the Hudson River was ever our source of commerce. And now it’s what is bringing us back.”

Visit Main Street on a Second Saturday evening, and the pulse of the city is ample proof that Beacon is indeed on its way back. Many happy returns!