Gallery hosts show of Japanese-style prints

By Alison Rooney

Mokuhanga is making a comeback.

The Japanese wood-carving process, developed in the 17th century, was rarely taught in the U.S. and a few decades ago was even faltering in Japan as techniques imported from the West — etching, lithography, silkscreen — became popular.

But the internet has helped introduce mokuhanga to “people with an interest in printmaking, Japanese culture and the interplay of historic and contemporary ideas,” explains April Vollmer, the author of Japanese Woodblock Print Workshop and one of the artists who contributed to a show, Mokuhanga Wood Prints, that runs through Sunday, July 1, at the Buster Levi Gallery in Cold Spring.

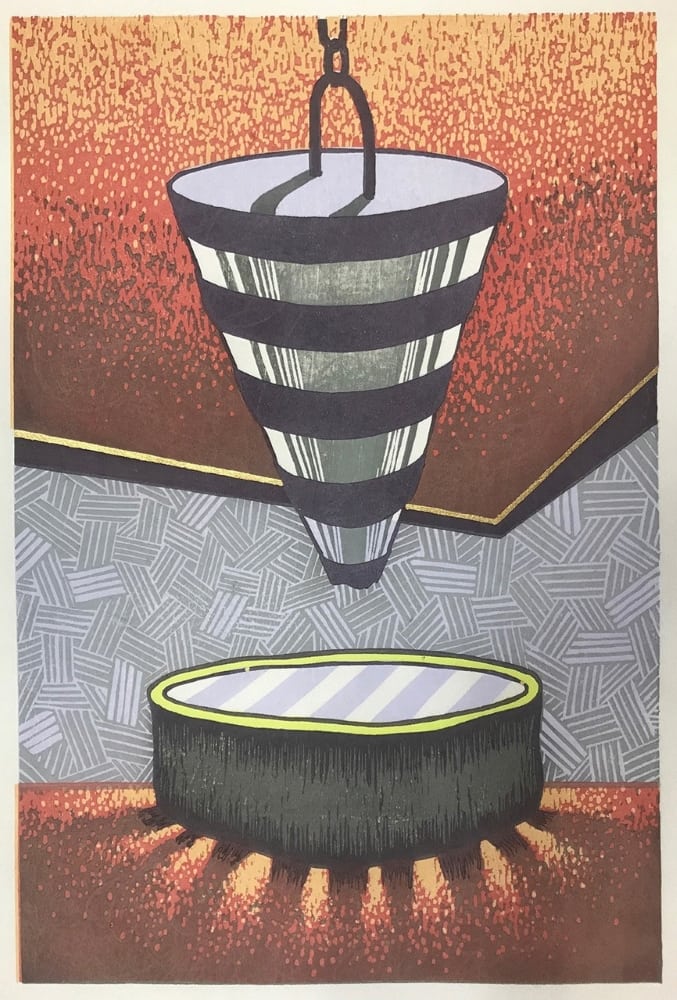

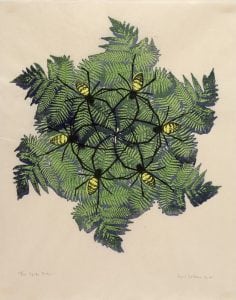

Traditional woodblock printing, of the type developed in Japan during the Edo period (1603-1868), is a not picked up quickly. It takes years for artists to achieve the balance of technique and temperament. Besides Vollmer, 10 other artists who craft their works using variations on the elements of carved wooden blocks — a flat disc, hand printing and cutting — contributed to the show.

Mokuhanga is the Japanese word for the process, which actually originated in China and Korea before reaching its heights in Japan with the creation of the Ukiyo-e prints, the multi-color depictions of life and landscape described as “pictures of the floating world.”

Most mokuhanga prints are produced with water-based ink and watercolor brushed onto blocks (rather than rolled), then printed with a circular, flat “baren” disc (instead of a rubbing tool or press) onto washi (handmade paper).

Traditionally, an artist would first prepare a sketch, then a detailed drawing, then a block carving made transparent with oil, then outline it with a knife, then carve and chisel. Each color was printed separately, and the colors aligned through devices called kento, which kept corners fitted.

What Inspires Them

The artists who contributed to the Buster Levi Show express a variety of motivations for working with the method.

Yoonmi Nam, raised in South Korea, says, “I am interested in beauty, irony, impermanence and the common and extraordinary way we structure our surroundings.”

For Ralph Kiggell, who lives in Thailand, “there is something compelling about carving a design on one material and transferring it to another.”

Melissa Schulenberg, living in upstate New York, thinks of her work as “a process of building my own ‘alphabet,’ forming visual vocabularies into new compositions.”

And the focus for Katie Baldwin, of Huntsville, Alabama, is the “relationship between drawing and print. When I am drawing, I am working much more spontaneously. I generate images in response to the things I see. I work quickly, generating lots of work, most of which isn’t particularly resolved. But out of the work, there are small moments or lovely images or surprising seeds of ideas that lead into ideas for prints.”

Pigments were ground and given the right consistency, then applied to the block, with paper laid on top, and the rubbing done with the baren. The process is repeated for each color, in a fixed sequence. Shading was done with brushes or by wiping or rubbing with cloth.

Ursula Schneider, who curated the Buster Levi show with Lucille Tortora, has been making woodcut prints since the late 1980s, drawn by the colors, their luminescence and transparency. The Hudson River is a favorite subject.

“Printing is like a meditation,” she says, “You have to be so focused.”

Schneider says she wanted to see in one place the work of the many artists who make mokuhanga prints. “There are so many different approaches to it,” she says. “One artist weaves them together, another uses a log.” The artists who contributed live around the world, including in Japan, Thailand, Argentina and the U.S.

The Buster Levi Gallery is located at 121 Main St. The gallery is open Friday to Sunday from noon to 6 p.m. See busterlevigallery.com.