Garden design for the long term

By Alison Rooney

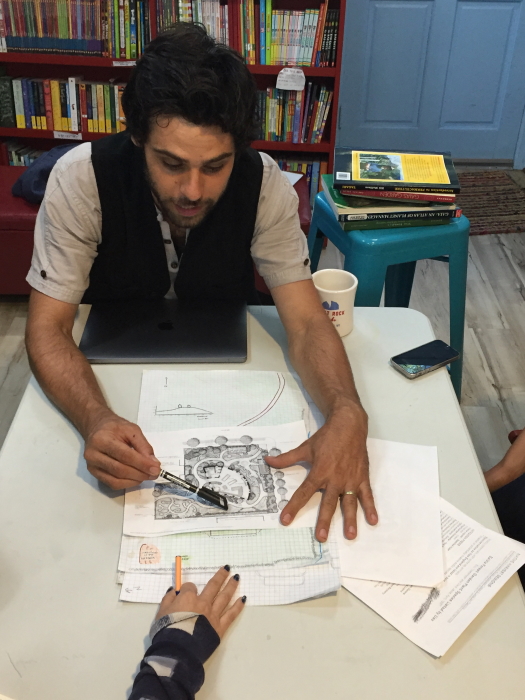

Permaculture may sound intimidating but, as Colin Wright explained during a workshop on Aug. 14 at Split Rock Books in Cold Spring, the word is simply a fusing of permanent and agriculture and describes a system of garden design that “recognizes the value of people and conservation.”

Wright, who is a member of the Permaculture Arts Collective and also manages the Cold Spring Farmers’ Market, traced the principle to the early 1950s, when it was known as “agro-forestry” and determined to green America with trees.

“Two Australians took it up and made a bunch of design systems that can be scaled up and down and changed to suit wherever you are,” Wright said. “Permaculture systems are modeled on natural eco-systems: What is in that energy cycle will stay in that cycle.”

Wright asked the attendees to introduce themselves and explain what they hoped to take from the workshop. The participants included a digital product designer who said he understood permaculture philosophically, but needed more information on how to implement it on his property, much of which is on a slope, and a couple who bought a house in Cold Spring and were “excited to have a yard, but it’s shady and wet. We don’t have much experience in the natural world.”

After making a few suggestions, Wright explained 12 principles of permaculture garden design:

Observe and interact. Pay attention, see what’s working. Where is the sun rising and setting? Is it windy? Part of the joy of being a permaculture person is being able to say, “I’m not tied to making it most efficient right away. How can I improve the land for the long term?”

Catch and store energy. For example, water. What are you doing with your water? With such unpredictable weather, you should have water stored. It’s easy to do with a gutter and a rain barrel.

Obtain a yield. Try to skim as much as you can off nature. Mushrooms are a great example. If nature is offering freebies, take them.

Apply self-regulation and accept feedback. Maybe you don’t need to take everything; leave some for nature.

Use and value renewable resources and services. Use solar-power and other natural energy sources; wean yourself off fossil fuels.

Produce no waste. Everything can be used and reused.

Design from patterns to detail. An example: often a spiral is a symbol of permaculture. Look for patterns in nature and use them as a blueprint for a way to build.

Integrate, rather than segregate. It’s not an and/or approach, it’s both. How does an organic design system fit into a modern approach? Think, “OK, that’s here — what can I do to make it better?”

Use small and slow solutions. Implement them over time. It’s about finding what works, small-scale and, over time, developing it.

Use and value diversity. Example: it’s difficult to be an organic fruit grower. Fruit trees get pulled out after five years because they’re overgrown. It’s resource intensive. Look at what actually grew here, traditionally. Use wild apples; don’t bring in a bunch of trendy trees that are only going to work for a few years. Resiliency is an inherent component. We’re in a reductionist age of gardening. It’s a much more complex holographic picture, rather than a linear one.

Use edges and value the marginal. Use the edges as a bio-diverse area.

Creatively use and respond to change. If you notice it’s windier than it used to be, consider wind power.

Taking the first steps can be daunting, so Wright suggested analyzing in terms of zones, calling it “a nice way to think about how to set up a space. What do I want close to me? What won’t I visit very often?

“Break your property into zones, for example: Living (Zone 1) — the place where you spend part of each day; vegetable garden (Zone 2) — a place you go to frequently, but not every single day; Zone 3 could be berries. Zone 4: compost. Zone 1 should be close to your house, while Zone 5 could be a not-nearby orchard. All paths count as Zone 1.”

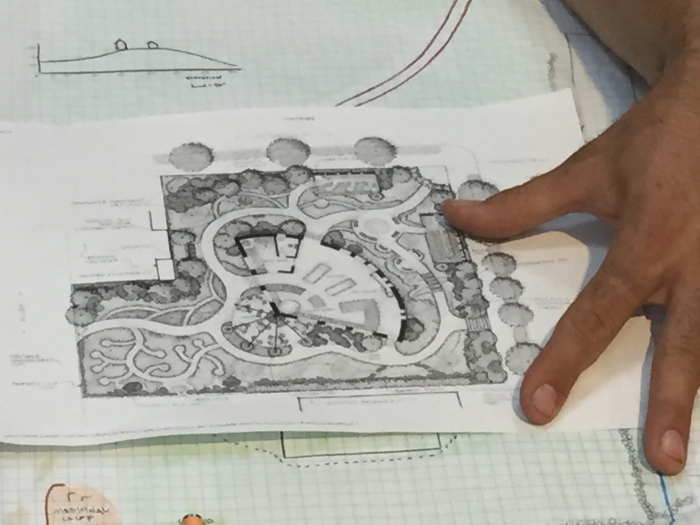

Wright then described a number of permaculture techniques. Among them are spirals which can contain a lot of microclimates, swales, raised beds, trenches and terraces, including those in a “keyline design,” which is a method of building terraces that channel water along the length of the property.

Wright advocated planting in “guilds,” or communities of plants that have similar needs. “Guilds are like plant companions,” he said. Wright also encouraged shifting away from annual crops to perennials.

The session ended with a design exercise, in which participants used graph paper and colorful pens to draw their properties and structures, then brainstormed on permaculture features. Wright examined each map, offering suggestions.

Wright said he plans to present additional workshops at Split Rock as well as a workshop and foraging hike at Boscobel in Garrison in October.