Folk singer and longtime Beacon resident Pete Seeger would have been 100 years old today (May 3), and celebrations and sing-a-longs are scheduled across the country, as well as the release of a box set that spans his career and includes 20 unreleased tracks. We asked those who knew and encountered Pete and his wife, Toshi, to share stories. The contributions have been condensed for clarity and space.

Folk singer and longtime Beacon resident Pete Seeger would have been 100 years old today (May 3), and celebrations and sing-a-longs are scheduled across the country, as well as the release of a box set that spans his career and includes 20 unreleased tracks. We asked those who knew and encountered Pete and his wife, Toshi, to share stories. The contributions have been condensed for clarity and space.

Download our special section as a PDF

Freddie Martin

On a Monday evening, Jan. 27, 2014, the day Pete died at age 94, I opened a letter from him containing the chord chart and lyrics for a song we had worked on together for some time, “Peace Will Prevail.” It was based on an ancient Irish air.

In late 2013, Pete asked the song circle at the Beacon Sloop Club to practice civil-rights songs for a citizens’ march on the upcoming Martin Luther King Jr. Day. While rehearsing the songs with the Spring Street Baptist Church choir, I realized “Peace Will Prevail” needed a gospel ending, so I wrote Pete.

From his hospital room, Pete had penned a note atop the song sheet, referred to a chord change I had made, thanked me for “working on it” and encouraged me: “You keep on!” It was classic Pete, giving of his spirit and energy to others, giving until the end.

Florence Northcutt

Little did I think some 35 years ago, while on a ferryboat trip from Algeciras, Spain, across to Morocco, hearing a familiar song coming from the loudspeaker and singing along with a number of passengers who knew it as well as I did, that I would one day live in the same community as the song’s performer. “We Shall Overcome” reached to the far corners of the world, and its message is as powerful as it was that day during the height of the civil-rights movement.

I feel privileged to have known Pete and to have seen him right here in our city working quietly, consistently and diligently to build awareness about our beautiful river and protecting our environment. He has raised our consciousness in his modest, humble way, and our world is a better place, thanks to Pete.

Erin Giunta

In 2013, I found myself in line behind Pete at the Beacon Natural Market. After he left the store, he got into his sticker-covered green SUV and sat there for a while. That’s when I noticed something by my feet: Pete’s car keys! I went outside and said, “I think these are yours, Pete.” “Thank you,” he said. “I thought I was losing my mind.” “Not yet, Pete. Not yet,” I said.

Later, within a week after Toshi died, I let him go ahead of me in line at Rite Aid. The clerk greeted him with a big smile and, “Hello, Mr. Seeger!” As he waited for the prescription to be filled, I said, “I’m so sorry about the loss of Toshi. I know she was a wonderful person.” He took my hand and said, “Thank you. She’s the reason I was able to do what I did. It was all because of her.”

Sara Dulaney

Having been raised listening to The Weavers, I was excited to learn about 1981 that they would be singing at something called the Clearwater Festival. I made my way, solo, from Manhattan into the wilds of the Hudson Valley on a drizzly day.

I felt moved to write fan notes to each of them. To Pete, I wrote that my late great aunt, Mabel Spinney, had run a school that he attended in Litchfield and that her sister, my Aunt Milly, had observed, “We never thought he’d amount to anything.”

A short time later, I got a postcard from Pete with a little banjo drawing. He said that Aunt Mabel’s school had been one of the most important experiences of his life. Pete said that Springhill School (now Forman School) encouraged him to learn in his own way. He took up the job of running the newspaper, and he felt he had a voice.

The last time I saw Pete, he was putting his recyclables at the foot of his road. Pete answered his own mail. He emptied his own trash. And he amounted to something.

Linda Richards

When I was the education director at Clearwater, the nonprofit founded by Pete and Toshi, he called the office one January afternoon to talk about a tent idea he had for that year’s Great Hudson River Revival. Pete was always thinking about more ways to get more people involved in everything.

As I took notes, Pete asked if I’d like to come over to talk more. “Do you have ice skates?” he inquired. “Ummm … not on me,” I replied. “No problem – we have lots of skates here.”

So I went over to the Seegers’ and ate dinner with Toshi and Pete and their granddaughter, Moraya. Afterward, I went over to the wood stove and saw a mountain of skates. Each winter, Pete would hose down the circular driveway (at 2 a.m.) to make a rink. Pete put on skates and we skated around to the music of steel drums he piped into an outdoor sound system.

I remember seeing the moon through the trees that cold evening and thinking this was one of those nights you cherish for a lifetime.

Tom Chapin

It began in 1957, near Andover, New Jersey, where we spent every childhood summer. Our Aunt Happy brought out an album called The Weavers at Carnegie Hall. We were hooked from the clarion bugle call of Pete’s five-string banjo on the first song, “Darlin’ Corey.”

To our amazement, Grandma Chapin had a five-string banjo in her basement. We bought a copy of Pete’s book, How to Play the Five-String Banjo. I got a cheap steel string guitar, memorized chords and started using fingerpicks because Harry was so loud on the banjo. At our first public performance as the Chapin Brothers, we played three songs by The Weavers.

In 1975 or 1976, I was backstage at Huntington High School on Long Island with Pete before a benefit concert. A reporter asked Pete: “You’ve spent your life doing concerts for causes. Has it made a difference?”

Pete thought a moment, then said in his calm, measured way: “I don’t know. But I do know that I’ve met the good people, people with live hearts, live eyes and live minds.” This was a quintessential Seeger answer, moving the conversation toward larger issues and the people he believed deserved credit.

Michael Bowman

When I was in college, I got lost hiking between Breakneck and Mount Beacon and ended up in some guy’s backyard. A tall man came out asking if I needed help and with a smile pointed me down his driveway toward Route 9D. Only later did I realize who it was.

Jennifer Blakeslee

At the 2013 Strawberry Festival, I asked Pete if I might take his portrait. Afterward I thanked him for everything he’d done for Beacon and the environment, and he said, “Ahhh, but you don’t know the foolish things I’ve done!”

Stacy Labriola

Many years ago Tony Trishka was recording a banjo retrospective and wanted to include Pete. So he invited Pete to come to my husband Art’s studio at our home in Garrison. Pete came down from Beacon and regaled the group with hours of recorded stories and did some banjo playing, as well.

After a day of recording, Pete said his goodbyes and headed out. About five minutes later there was a knock and it was Pete with a broken headlight he had found when exiting the driveway. He handed it to us and asked that we recycle it properly. As he left, the engineer on the project, Joe Johnson, said, “There, you have your Pete Seeger story!” Happy birthday, Pete!

Stephanie Roland

Michael Mell

We had just moved to Cold Spring and my eldest son was in grade school at Haldane. At a “Differences Day” celebration in the cafeteria, Pete Seeger walked in, banjo in hand, along with two parents who were musicians, as if it were the most natural thing in the world.

I was gobsmacked. The last Pete Seeger concert I attended was at Carnegie Hall. After that I would occasionally see him, with wool cap and plaid shirt, exiting Angelina’s with a pie. I regret never having said hello.

Robert Cutler

In 2012, Toni Bryan and I interviewed Pete at Boscobel. We were producing an audio tour that included stories about the river.

He drove down from Beacon on a snowy day with a banjo in his little black Honda. After about two hours, we had everything we wanted, including a performance of “Waist Deep in the Big Muddy.” But as we wrapped up, he asked if we’d like to hear three new verses that Toshi had written for “Turn, Turn, Turn.”

There we were, three of us in a tiny room, and Pete serenading us with one of the greatest songs of the 20th century.

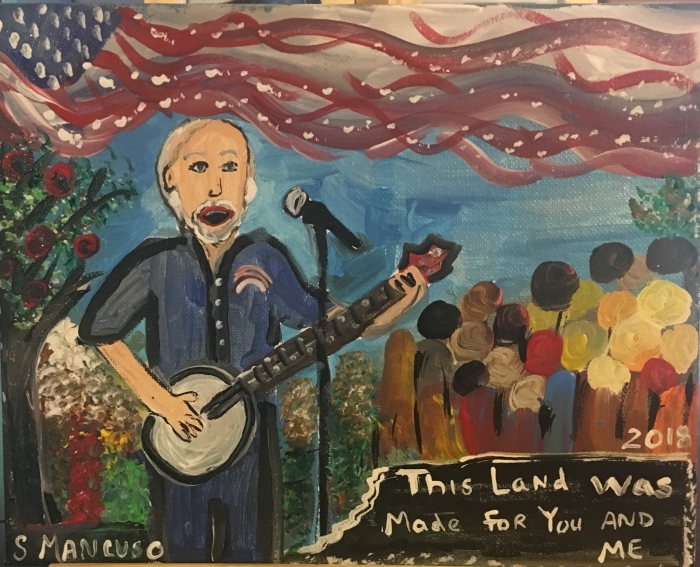

Suzanne Mancuso

Roger Coco

In the early 1970s, I led wilderness trips near the Hudson River for American Youth Hostels. The protest against a proposed pump storage plant on Storm King was in full swing. Pete had sent a postcard with a photo of the Clearwater to the AYH office asking if “Strider” (my nickname) could guide a group of protesters and reporters through the woods and valleys with Pete yodeling and singing against the echoes of the waterfalls of Stag-nun Creek, up and over Butter Hill and to the bottom of Storm King.

I had no idea who he was, and I don’t know how he got my name. What would a peace-loving liberal want with an old-time conservative like me? We were lucky that day, there was no trouble. Instead, we stood victorious at the bottom of Storm King, and Seeger whipped a monopoly.

John Cronin

There we were, in Beacon in 1972, and this big boat comes sailing in, and, for God’s sake, there’s Pete Seeger on the bow, and he yells to the crowd: “We’re going to be rebuilding this dock, so I’m looking for volunteers.”

I thought, I get to hang out with Pete! The great thing about spending time with Pete Seeger is that being with Pete is pretty much like being at a Pete Seeger concert. If we started slowing down, you know, Pete would start singing a work song or a sea shanty to get us all banging away. When his back got stiff, he would stand up and turn toward the Highlands and start yodeling.

Between all these things, he’d give little homilies. He’d say, “Well, you know, if we all work together, we can clean up the Hudson River.” And I thought, this guy is just out of his mind, because this is a damn dirty river, and it’s an awful big river, and there’s just no way.

He’s like a combination of a Pied Piper and a Johnny Appleseed, and you couldn’t spend that much time with Pete without him cajoling you into something.

Damian McDonald

This is one my favorite shots of Pete. You can see the excitement and joy on his face as he headed for the Hoot at Little Stony Point in September 2006.

Vickie Raabin

I was lucky enough to have been in several concerts with Pete so he knew me by sight, referring to me as “that little music teacher.” I had bought a used banjo and had it sitting in my studio on Main Street when Pete walked by, stopped, came in and started playing it. He fixed the bridge and asked if I minded — of course not! To this day, whenever I get new strings the bridge is always put back the way he adjusted it.

Brent Spodek

If you move to Beacon, or even think about moving to Beacon, someone will tell you that this is where Pete Seeger lived. When I moved here, I knew where Pete’s house was before I knew where the hardware store was.

Although I can’t carry a tune, I organize a monthly adult sing-a-long. When I complained to Pete about my lack of musical leadership skills, he said, “It doesn’t matter if you can sing; it matters if you can bring other people together to sing.”

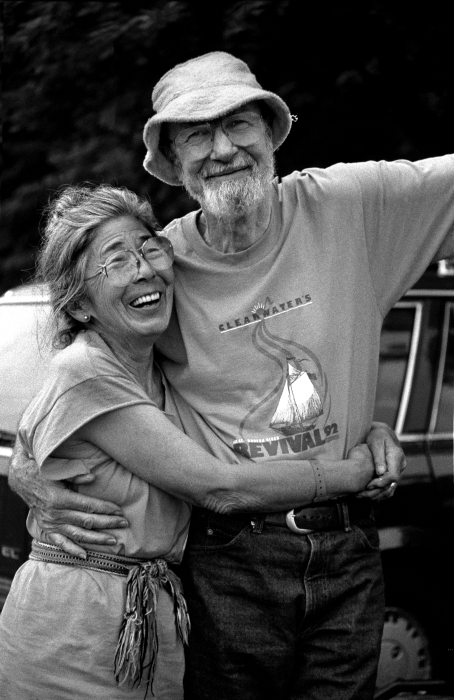

Steve Sherman

I had gone to the parking lot at the 1992 Clearwater festival and I saw Pete putting something into his car. Toshi drove up in a golf cart (she was running the festival) and I asked if I could take a photo of them. Unfortunately, Pete wasn’t in the mood. After I said to Toshi that Pete looked tense, she grabbed his ass, he jumped, and she threw her arms around him.

Marc Breslav

Pete hated being famous. I ran into him one day at Grey Printing in Cold Spring shortly after the Great Hudson River Revival had been closed in the middle of the day due to lightning.

“Hi Pete,” I said.

He grimaced, avoiding eye contact.

“How did Clearwater do money-wise with that storm?”

The grimace brightened to a frown.

“You know, all we have to do is get a quarter-inch thick rubber carpet for the whole site,” he said, still averting his eyes.

“Just have to make sure it’s recycled rubber, Pete!”

He looked me in the eye, smiling broadly.

Flora Jones

Ellen Gersh

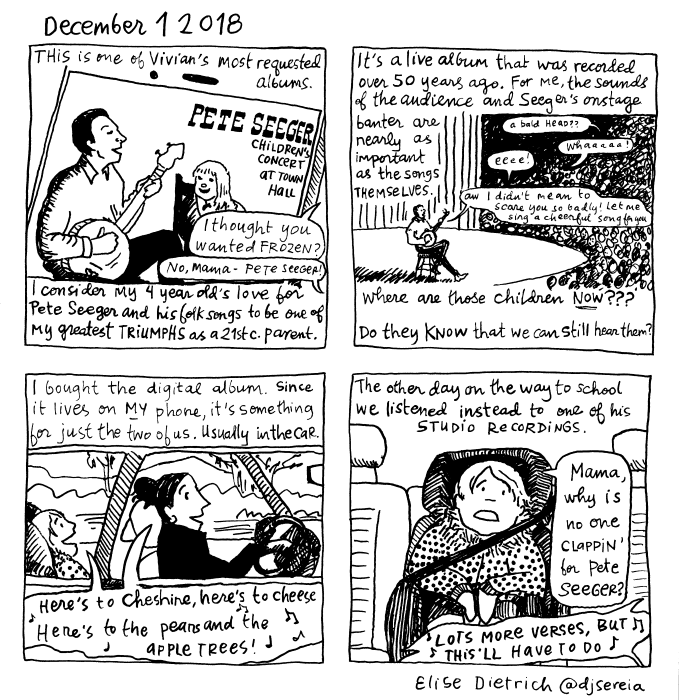

Pete was really involved in the local schools. He played for children because he was blacklisted and couldn’t perform elsewhere. He realized that social music was dying, that people don’t sing anymore since the invention of the phonograph.

People get caught up in the celebrity of Pete, but he hated people fussing over him. The best way to honor him is to sing and encourage young folks to sing. Also, to join the fight for equality for all people. If everyone put their energies into fighting the fight that Pete did, we would be on the right track.

James Gurney

Besides hearing him play at festivals in the Hudson Valley, my family got to know Pete through a tattered copy of his songbook. In 1991, when my son, Dan, was a 4-year-old budding accordion player, he wrote Pete a fan letter, and Pete wrote back on a postcard with a drawing by Ed Sorel showing Pete with his banjo outrunning the Horsemen of Time. At his concerts, Pete made every person feel that they had a good enough voice.

Tink Lloyd

Pete knew my partner Joziah Longo and me by sight from the many concerts we had played together over the years [as The Slambovian Circus of Dreams], so he recognized us one day in October 2013 when we walked into the Foundry Cafe in Cold Spring. He had gotten off the train and needed a ride to Beacon, which we were happy to provide. As we drove, and at his home, he gave us an update.

He was doing another edit of his autobiography and had photos on the wall from his whole life. He shared the history of New York as we drove north on 9D, how the quarry at Breakneck Mountain provided the stones for the Brooklyn Bridge, the first trains into New York City, the beginnings of Smithsonian Folkways, the first time he met Martin Luther King Jr. at the U.N. (and saw J. Edgar Hoover drive by in a black limo), being blacklisted and Toshi having to become his booking agent (she built the performing circuit that was the foundation for Baez, Dylan, etc., to tour).

When we asked him what he thought we could learn from him and how to carry on, he said. “If you do what is right, it has an effect not only on the future, but on the past, like ripples in water.” That is the hope he felt just four months before he passed.

Phil Ciganer

In the early 1970s, when I came to the Hudson Valley to open the Towne Crier, I heard Pete Seeger lived in Beacon, and I hoped to meet the great man. Sure enough, when one of our first scheduled performers was detained by car trouble, Pete showed up and volunteered to “fill in.” That, I soon came to learn, was “typical Pete.”

As we got to know each other, I became involved with Clearwater and Pete’s passion to reclaim the Hudson River. “Phil,” he said, “if you want to change the world, you start at home.”

One year, I helped book Pete at the New Orleans Jazz Festival. As we landed in New Orleans, I worried that I had blundered by bringing a folk icon with his banjo to a loud party of a festival. But sure enough, Pete charmed them immediately with his spirit and won them over with his songs. That’s when I realized how much he had come to mean to us all. Pete was that rare person who lived up to his ideals.

Dar Williams

Pete and I were doing a fundraiser and before I asked if he thought a recent biography of him had been accurate. He nodded slowly and said, “Yes, but there was one thing that didn’t seem right. He said I worried about my career. I never gave a shit about my career.”

I felt honored when Pete asked me to walk in the woods with him at a Clearwater festival. He wanted to point out the invasive species and alert me to events where people in waders pulled purple loosestrife out of the water. That was the day I leaned about the mile-a-minute vine.

Gene Deitch

Pete was an idealist, his mind sharply focused on brotherhood and sisterhood, and would barely discuss anything else. He was a pure propagandist for his ideals. He referred to himself as a “communist” in the purest Karl Marx sense. I loved him for his purity of heart and his idealism, as much as for his songs.

When he was on a world tour in 1964, about to come to Czechoslovakia, where I have lived since 1959, he felt he would be in a place of like-thinkers, and would be warmly welcomed in a Communist-ruled country. What he didn’t realize was that he was coming into a country that followed whatever was written in the Soviet newspaper, cleverly named Pravda (“Truth”).

Pete and his family were assigned to a hotel restricted to Western “capitalist” business people. He never had a chance to meet any Czech officials, and was booked into obscure venues and given virtually no press coverage. Nevertheless, his concerts were packed, due to word-of-mouth and a few posters. Pete was perplexed by the lack of official support, and I had to explain it to him in the most careful way. Ironically, four years later came the short-lived freedoms of the Prague Spring, and a label called Supraphon bought tapes I had made of Pete’s concerts so it could release them as an album.

Robert Murphy

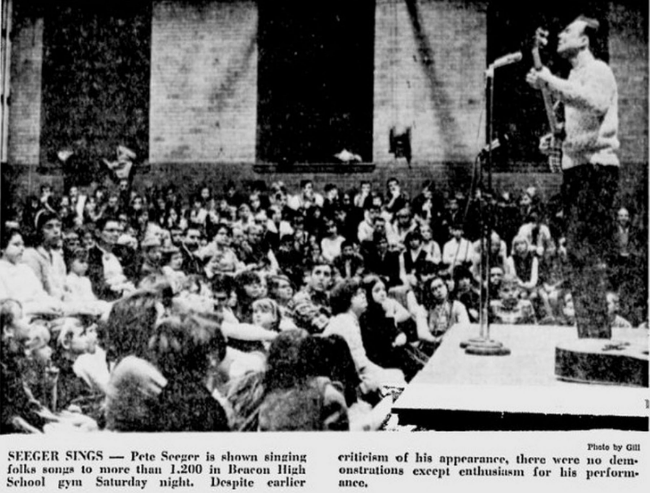

In 1965 Pete was asked to perform a concert in the Beacon High School gym to benefit the scholarship loan fund of the Beacon Teachers Association. The Vietnam War was escalating and Pete was an early and vociferous opponent. A few weeks earlier, Pete had performed a few anti-war songs at Moscow University in the Soviet Union.

Feelings were still raw among some residents about the singer’s failure in 1955 to assist the House Un-American Activities Committee. Immediately after the concert announcement, a committee of 12 civic, fraternal and religious organizations formed to stop it, criticizing the board for allowing a “figure of controversy” to appear before impressionable youngsters.

However, the letters that poured into The Evening News were about 5-to-1 in favor of the show. Writers invoked principles such as freedom of speech and the right to dissent.

On the night of the concert, Nov. 27, 1965, Police Chief Sam Wood and five officers patrolled the gym. There was no need. No one was there to protest. Instead, it was filled to capacity. Pete sang 25 songs over two hours, including “Old Dutchess Junction” sung to the tune of “Red River Valley,” and the concert raised $3,000 [about $24,000 today]. Perhaps hearts and minds were changed by this concert, and soon a community was to learn more about Pete and that … there is a time to every purpose under heaven.

Rob Abbot

In the early 1980s, a friend asked if I wanted to play with him at a folk festival at the Appalachian South Folklife Center. I agreed, although I only knew four or five chords.

I can’t remember what songs we played, but I do remember my shock being told we were “opening” for Pete Seeger on the makeshift outdoor stage. I’ve since learned that Pete played thousands of gigs from such stages, entertaining college students or playing from the back of a flatbed truck for farmworkers or serenading workers on the picket line.

I am proud to have shared a stage with this gentle man on a hot dusty Saturday afternoon in coal country.

Eliza Nagel

Here is Pete with my dad, Fred Nagel [below] in 2007 at a weekly peace vigil on Route 9 during the war in Afghanistan and Iraq. Pete carried the flag when he crossed Route 9 to sing a few songs with counter-protesters. Their favorite was “This Land is Your Land.”

Damon Banks

When we first moved to Cold Spring, my wife and I didn’t feel entirely comfortable. There isn’t a lot of diversity and the area has a lot of racist/anti-Semitic history.

Pete and Toshi saw me with my bass on the train platform one day, and Pete asked: “Do you live around here? Do you know about the history of this area?” I didn’t know who he was, so I rolled my eyes and said, “Yeah, I heard about it.”

He began to talk about how, because of his music, his political views and his “friends,” this area made it difficult for him to live in for many years. He said he stuck with it because of its natural beauty, his family and the strong friendships that developed. He thought that my presence as a local resident (and an African-American musician/teacher) was a very positive development and it would be great if I “stayed in the neighborhood.” He finally told me who he was (which blew my mind) and the three of us rode to the Bronx together. That experience inspired us to stay.

Nell Timmer

From 2003 to 2008, I owned a coffee shop in Beacon. Although it was pouring rain on Spirit of Beacon Day in 2004, we saw a hunched-over figure in a yellow rain slicker in the empty lot next door picking up garbage.

We went out to see if the person needed help and there was Pete. He turned to us and said, “You know, if everyone picked up one piece of garbage a day, the world would be a much cleaner place.” Needless to say, we went back inside and returned with our rain jackets and a garbage bag.

Joe Neville

It was the spring of 1966 and I was failing high school English. The teacher said, “Even if you pass the Regent’s exam, I will have to fail you unless you do something about it.” For the topic of my final report, I chose American folk music. I had a brainstorm (very rare). Instead of spending hours in the library, I would talk to Pete. My father, Doug, owned the general store at the foot of Mount Beacon. All the “mountaineers” frequented the store, including Pete, so I knew him quite well. I drove up his hill and he was in his yard, holding a handsaw. He said, “Hi Dougie [everyone called me that because of my dad], what brings you up here?” I told him and he said, “I don’t like that teacher, either; let’s see if we can’t get you an A.” And we did. Thanks, Pete.

Nathalie Jonas and Philip Nobel

Pete came to welcome The Living Room to Main Street in Cold Spring in 2011 and, in the course of the conversation, recited the Gettysburg Address for us.

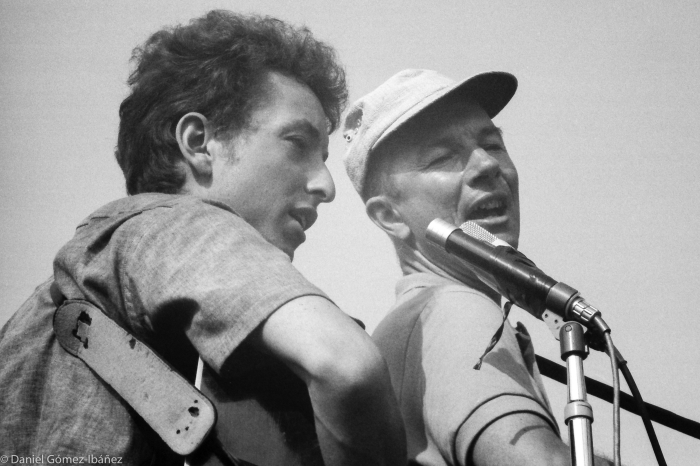

Daniel Gómez-Ibáñez

I liked Pete Seeger. He and I corresponded on a couple of occasions, and once, at my somewhat presumptuous invitation in the early 1960s, he came to my high school in Middletown, Connecticut, to give a free concert. He was a big hit with everyone, students and teachers. The idea to invite him came out of a conversation with my music teacher when I asked why she didn’t include folk music as part of the curriculum.

Al Scorch

Pete was born as broadcast radio ushered out the player piano and an infantile record industry played the role of folklorist in trying to find the latest hillbilly and race hits. He stood up to things that usually break a man: political assassination at the hands of his own government and offers of big money. He left this world a better place but inequality and injustice remain in newer, slicker forms.

A lot of people think Pete was enraged when Bob Dylan “went electric” in 1965 at the Newport Folk Festival but he said he was actually appalled at the sound quality. The P.A. had to be cranked so loud that it began to distort and the vocals were rendered unintelligible. Pete was pissed that a song as good as “Maggie’s Farm” was being garbled to mush.

Another classic Pete moment of unwavering commitment to quality sound is him gently explaining mid-song to a massive crowd that clapping along at Carnegie Hall doesn’t work.

More on Pete at 100

- Remembering Pete

- Moments from a Life

- When Pete Seeger Wasn’t Welcome

- 5 Questions: Jeff Place

I interviewed Pete at the 2008 Beacon Strawberry Festival, naively assuming we’d sit for a leisurely chat. Wrong! I could barely keep up, taking notes on the fly, as Pete hustled about at breakneck speed. He provided the quickest, clearest, most succinct answers I’ve ever encountered. When I asked about his hopes for the McCain-Obama election he said simply, “Whoever wins, I hope they have the ability to bring together those who disagree.”

I was part of the team that reopened the Paramount theater in Peekskill in 2013. We hosted one of Pete’s last concerts, a fundraiser for the public-radio station WAMC.

The Paramount has three flights of dressing rooms with some relatively steep stairs. With that in mind, I had a dressing room designed for Pete at stage level. He said it was nice but asked, “Where is everyone else?” When I told him, he proceeded with banjo and guitar to march upstairs. He had the strength and will of people 40 years his junior.

When I heard a news report that Pete had died, it was like hearing the Big Dipper won’t be coming over the mountains any more.

Living in the Hudson Valley, it seemed like we were always catching sight of Pete — at potlucks, jams or rallies, or just slinging his banjo case through Grand Central. He’d use his beloved voice and music and presence to help wherever he could: to unite communities, move people to action or simply share joy.

The year I swam the Hudson River from Newburgh to Beacon, the first thing to greet my blurry eyes as I rose from the water was old Pete himself, picking up litter at the river’s edge.

We were privileged to hear him at the Towne Crier, where he was warming the stage with a Weavers tribute band. I was frustrated trying to take a picture because there was so much light pouring from the stage. But the next morning, magically, one photo included an image of a bodhisattva, a painting of an old saint, with his symbol of deliverance.

I loved when you told that swim story at our Breakneck Ridge Revue at the Towne Crier a couple of years ago, Irene!

My wife, Constancia Dinky Romilly, and I were in the New York City Labor Chorus for many years. On June 7, 2001, we had a concert at the Town Hall with Pete and, at the end of the concert, he gave us each a copy of his latest book of songs.

Once I was given a special gift, the opportunity to build something with Pete. We were visiting Pete and Toshi and Pete mentioned he wanted to retrieve some logs he’d cut for his wood-burning stove. He said the logs were across a small creek, and he’d cut a log to place over the creek as a bridge. He and I and his son, Danny, walked off to locate the log. When we got there, Pete realized he needed an ax to trim the log. Although he was about 90, he trotted off down the trail back to the house and returned in a few minutes, not even out of breath.

For those of us living in the Hudson Valley, we have been so extraordinarily privileged for Pete to have been our neighbor and friend. He was truly a giant of the 20th century, giving inspiration to every movement for peace, justice and a cleaner, survivable future.

Pete and Toshi were neighbors to me and my late husband, Art Kamell, and we considered them our best friends. Pete taught us that music, kindness and friendship will change the world step by step. He continues to be with us every minute of our lives whether we are walking the walk during vigils and demonstrations, talking the talk cleaning up his beloved Hudson, or singing his songs.

Our favorite memories of Pete are of him playing music with anyone who showed up at the Beacon Sloop Club meetings with an instrument or the desire to sing. The sing-a-longs showed us the power of song in action. Meeting Pete and sharing songs and meals with him, Toshi and others at the Sloop Club profoundly affected our family and our devotion to environmentalism, social justice and the power of community. We feel so fortunate to have met him.

If you wanted to talk to Pete on the phone, you had to pass muster with Toshi. She was a tenacious gatekeeper with a long-standing animus for journalists, going back to the Red Scare era when Pete was excoriated in the press. In 2001, to secure an interview for Hudson Valley Magazine, I mentioned my acquaintance with folk singer and banjo player Rik Palieri, who had worked with Pete and the Sloop Singers in the mid-1970s.

It worked! Toshi passed the phone to Pete. A few weeks after my interview, I received a long letter from him detailing an idea for a floating swimming pool in Beacon on the Hudson — which opened, thanks to Pete and other community supporters, in 2007.

In the last 1970s and early 1980s I was the sign-painting coordinator for the Clearwater festival. We made a lot of parking signs, direction signs, seating signs, beware of poison ivy signs, all with a festive feeling.

Pete would hang out at breaks in the big room and tell stories of this and that or you would see him or Toshi riding about “supervising” on golf carts. The night before we would be looking out at empty fields that were ready for the thousands that would enter under the rainbow arch … and they did.

About 15 years ago at the Beacon Sloop Club Circle of Song, when it was my turn, I sang “Amazing Grace.” Pete stood up, applauded, and then came up and joined me in singing after he shared where the song originally came from. I will always remember this very special moment.

In this photo, at Peace Corner in Wappingers Falls, at the corner of Route 9 and 9D, is Roland Mousaa, who was very close and worked with Pete since 1969, the blue-haired woman is me (Princess Wow), Chris Ruhe, Caitlin O’Heaney, Pete and unknown. Most Saturdays Pete and friends would gather, sing, eat, and promote peace.

Dear Diary:

I had lived and worked in Manhattan for many years, but when my wife and I married in 1991, we decided to move to Cold Spring and try to balance country life with commuting to our jobs in the city.

One night after work we went to see a friend’s play in the Village. We went out for a bite afterward and wound up catching a late train to Poughkeepsie. As was our habit, we got on the first car because our apartment was just a block from where we would get off.

The car was full when we left Grand Central, but the only ones left after we stopped at the Croton-Harmon station were us, sitting in one of the middle rows, and an older man who was toward the front of the car.

As the train pulled out of the station, the older man stood up and took a case down from the overhead rack, took out a guitar and began to play. We could tell that he was very good, so we moved closer and sat next to each another in a corner four-seater facing him.

[From “Metropolitan Diary,” The New York Times, Dec. 27, 2020]