Despite earlier ban, Coast Guard issues directive

Halloween may be over, but an issue that many Highlands residents thought was settled has unexpectedly returned from the dead: the fight over where barges can anchor long-term in the Hudson River.

After a proposal to add 10 new anchorages between Yonkers and Kingston met with fierce resistance and came to an end only with action by Congress, the U.S. Coast Guard declared in a recent bulletin that the 2021 ban does not apply north of Tarrytown, including at Philipstown and Beacon.

Also: It’s effective immediately.

The idea that a 462-word memo could counteract Congress caught lawmakers and environmental groups by surprise. One person contacted by The Current said their initial reaction was that the bulletin had been issued by mistake. Another, John Lipscomb of Riverkeeper, said he was baffled. “What’s the end goal of doing this?” he wondered.

The conflict began in 2015. In response to reports that commercial vessels were anchoring illegally in the Hudson, the Coast Guard issued a bulletin that clarified where barges could park. It identified seven anchorage grounds, but only one, near Hyde Park, was north of Tarrytown. “Except in cases of great emergency, no vessel shall be anchored in the navigable waters of the Port of New York outside of the anchorage areas established in this section,” it wrote.

The Tug & Barge Committee of the Port of New York and New Jersey responded with a request for more anchorage grounds, citing an anticipated boom in the oil market because of the lifting of a federal ban on crude exports.

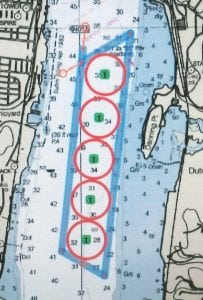

The Coast Guard in 2016 proposed for 10 new anchorage grounds between Yonkers and Kingston, with space for 43 barges. They asked for public comments and received more than 10,000, with 98 percent opposed.

Opponents acknowledged that the Hudson is a “working river” but feared it would turn into a parking lot of barges filled with oil, biding their time as they watched prices and picked a profitable time to rush to the Port of Albany to sell. Environmental groups pointed out that more parked barges increased the chances of a spill; the Hudson is a muddy, turbid river, meaning any spilled oil would quickly bind to the organic matter in the mud and then sink, making cleanup effectively impossible.

Conservationists noted that many of the new anchorages were in the breeding grounds of the Atlantic sturgeon and short-nosed sturgeon, two endangered species. The swaying of the anchors as the Hudson changes direction a few times a day would carve deep gouges in the sturgeon’s habitat, as the fish often keep to the river bottom as well as lay their eggs there.

Municipalities that had spent millions reviving their waterfronts objected to the idea of their revitalized towns now looking out onto aquatic parking lots with ships beaming stadium-style lights all night. (In fact, the lights and noise of barges parked illegally near Rhinebeck in 2015 prompted the initial complaints.)

The Coast Guard responded by suspending the proposal. In 2018, it released the results of a safety assessment that concluded that the new anchorages were not needed. Taking no chances, opponents pushed for a ban, which was inserted into the Defense Authorization Act of 2020. The act was vetoed by then-President Trump, but Congress had enough votes to overturn it.

At a January 2021 news conference, then-Rep. Sean Patrick Maloney, whose district included the Highlands, said the matter was now settled “forever.” He added: “In the future, if you want to undo it, you can come talk to us and tell us why you want to screw up the Hudson River.”

That future arrived in July, when the Coast Guard said that its 2015 bulletin had been mistaken when it referred to the seven allowable anchorage grounds as being within “the navigable waters of the Port of New York.” It said that “detailed research of the anchorage regulatory history” had revealed that the Port of New York encompass navigable waters within a 25-mile radius of the Statue of the Liberty, or to a point just south of the Mario Cuomo Bridge near Tarrytown. (The original Tappan Zee bridge was constructed there in the 1950s so that it would be outside the oversight of the Port Authority, and the state could collect the tolls.)

In short, the anchorage regulations end at the Cuomo Bridge. Anywhere north, barges can anchor anywhere they please, and for as long as they please, as long as they have adequate lighting, deep enough water and space to turn around.

Rep. Pat Ryan, a Democrat whose district includes Beacon, recently wrote to the Coast Guard for clarification. The response by Michael Emerson, director of marine transportation systems, was not reassuring, saying only that the Coast Guard is asking for “a collective evaluation on the outcomes” from its “clarification of the geographic reach of the Port of New York.”

Ryan described the response “woefully inadequate.” In a speech on the House floor on Wednesday (Nov. 1), he called on the Coast Guard to uphold the anchorage ban and for “every single Hudson Valley resident to join me in this fight to protect our river.” He is soliciting comments at patryan.house.gov.

In a statement, the Coast Guard said that “significant deliberation and review next steps are ongoing, and the Coast Guard will keep the public and all stakeholders informed with any changes or updates to ensure the Hudson River remains safe for all communities and users.”

On Friday (Nov. 3), State Sen. Pete Harckham and Assembly Member Dana Levenberg, whose district includes Philipstown, sent a joint letter to the Coast Guard voicing their opposition to the reclassification and demanding that the agency “take steps to immediately reestablish the geographic scope of the Port of New York to include all waters of the Hudson River and once again limit anchoring in the Hudson River to federally designated anchorage grounds.”

“Our communities vociferously opposed these anchorages just a few years ago, which perhaps explains this attempt to sidestep public comment or environmental review,” Levenberg said.

Drew Gamils, an attorney at Riverkeeper, said that the group reached out to the Coast Guard to set up a meeting but has received no response. If the Coast Guard declines to rescind the bulletin or clarify its language, “we do have some really good legal arguments,” she said, such as citing the Endangered Species Act or the National Environmental Policy Act, among other regulations.

Lipscomb said that, so far, he hasn’t seen a dramatic increase in barges dropping anchor for extended periods. There’s also less of a threat of oil cargoes than a few years ago because of new pipelines.

However, pipelines break or get shut down, and the absence of a current threat doesn’t mean that the bulletin should stand, Lipscomb said. “We want the Hudson protected, not from the volume of barges today, but from the potential volume of barges and potential future cargoes.”

Wait, they get to make a “mistake” like that, and use that mistake to benefit them or whomever, and it is effective immediately? No review? No meeting or two? Maybe a revision? The federal government can just do as it pleases; copy that. [via Instagram]